The US$ 70 billion global arms trade is by nature opaque and secretive, although deals have become increasingly commercial as suppliers compete to supply weapons and training. For African governments and entities that have the means to pay, or that are prepared to transfer natural resources as payment in kind, there is an apparently limitless supply of weapons to satisfy increasing demand. In April 2014, a year after an historic United Nation’s Arms Trade Treaty (UN ATT) was adopted by a majority of states, efforts to regulate the supply of weapons stalled as an insufficient number of countries ratified the treaty. Thus, in practical terms, the supply of weapons to Africa continues unfettered, at a massive cost to the region’s socio-economic fabric.

Arms Trade Treaty flounders

The ATT has the potential to significantly stem the supply of weapons to conflict situations. It aims to regulate the international trade in conventional arms, including small arms, battle tanks, combat aircraft and warships. In particular, it is intended to stop weapons flows to countries when it is known they could be used to facilitate genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes. The treaty would require arms suppliers to assess the risk of arms transfers, and governments to compile records of the quantity, value, model and authorisation for transfers of arms, alongside the identities of end users.

However, in April 2014, a year after the ATT was adopted by the UN General Assembly in New York, it fell short of the 50-nation minimum ratification required for the treaty to enter into force. Specifically, 43 states that initially indicated their support have failed to ratify the treaty; and of these, more than a third are African countries: Algeria, Botswana, Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, Somalia, Tunisia and Uganda. Many of these states do not have the capacity to implement the treaty, although this excuse cannot accommodate the full list of African countries that supported the treaty in the first place; nor does it accommodate the case of the United States (US), which has also failed to ratify the treaty after signing it.

Angola and Egypt were among the 23 countries globally that initially abstained from voting in April 2013 for the ATT, alongside China, India and Russia. In the meantime, arms transfers are continuing to countries in which serious human rights violations are known to occur. The London-based rights organisation, Amnesty International (AI), cites the example of the Czech Republic which, in December 2013, sent “tens of thousands of firearms to Egypt’s security forces, who have killed hundreds of protesters during demonstrations following the military’s ousting of President Mohamed Morsi.”

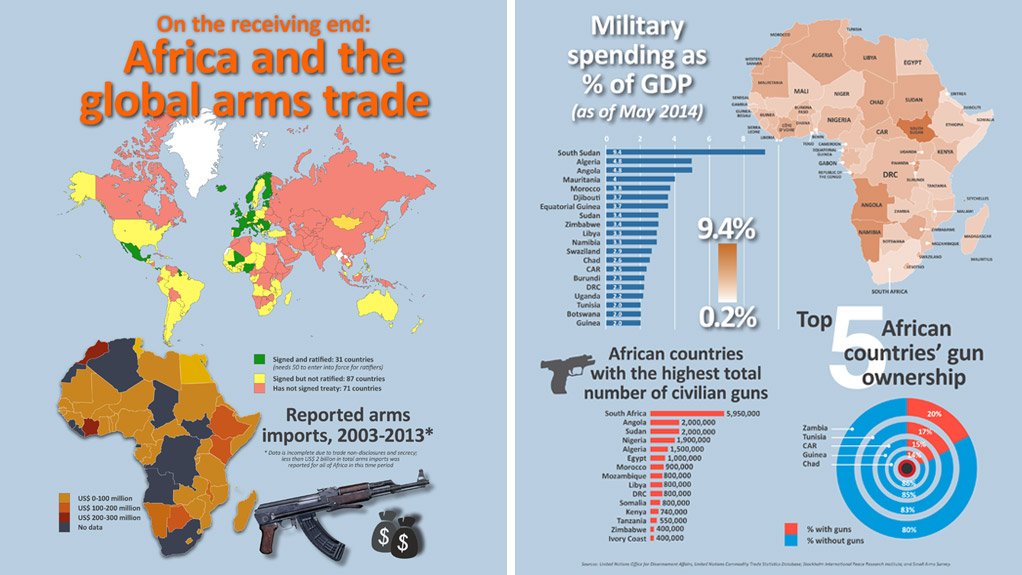

Figure 1: Africa and the global arms trade

ACMM’s latest infographic, entitled ‘On the receiving end: Africa and the global arms trade’.

Download the graphic in PDF format.

Africa’s biggest arms suppliers

In 2007, 95% of weapons and ammunition in Africa were estimated to be sourced from outside Africa, and this dominance of foreign supply is not likely to have changed substantially since then. African production of weapons is limited in scale and level of technology and, where it has developed, tends to be reliant on foreign licences for local production. South Africa, Sudan, Egypt and Nigeria are the only significant producers of weapons. Thus, Africa’s foreign transfers of weapons remain prominent, and they are renowned for their lack of transparency. According to the independent think tank Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the biggest consistent suppliers of arms to Sub-Saharan Africa are China, Russia and Ukraine, although this may change in any particular timeframe. Incidentally, all three of these countries have failed to sign the ATT. In addition, some exporters which are tiny on a global scale play a significant role in exports to individual African countries; for example, Jordan has exported significant quantities of arms to Kenya.

Russia is the world’s second biggest supplier of arms after the US – together, they accounted for 56% of all global arms exports over the period 2009–2013. Russia is a significant supplier to Africa, primarily through state intermediary Rosoboronexport. Africa accounted for an estimated 14% of Russia’s arms exports from 2009–2013. Russia’s military relationships with Africa have shifted to those based on commercial terms rather than those based on ideological support from the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, which were designed to counter Western interests in Africa. For Russia, arms deals are a means to forge influence and economic relations. Thus, its supply of weapons has expanded from Angola and Ethiopia during the Cold War to further include Algeria, Botswana, Ghana, Libya, South Africa and Uganda, among others. Russian arms products, including the popular Kalashnikov assault rifle, of which the most well-known is the AK47, have a strong reputation in Africa. Ukraine, which faces military problems of its own with Russia, reportedly delivered weapons to at least five African recipients, including Ethiopia, during the period from 2006–2010, with Africa accounting for 17% of Ukraine’s weapons exports during this timeframe.

There is substantial secrecy around exports of Chinese arms, but Africa is believed to account for 11% of Chinese exports of major arms from 2006–2010, during which period China exported significant quantities of arms to Sudan. This, combined with the fact that China is Sudan’s biggest trade partner, suggests that China’s official policy of non-interference in Africa’s sovereignty politics is open to interpretation.

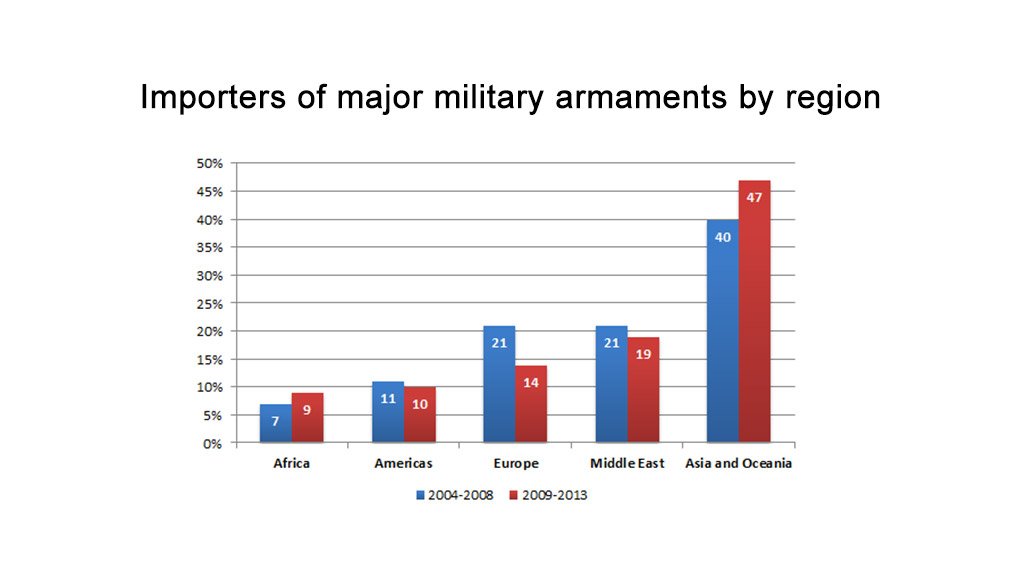

On the demand side, Africa’s biggest importers of arms from 2009–2013 were Algeria (accounting for 36% of imports), Morocco (22%) and Sudan (9%). While Africa’s share of global arms transfers is small, it is growing at the fastest pace in the world. Over the period from 2009–2013, the flow of arms to Africa increased by 53% compared to the previous five years, making it the recipient of 9% of all global arms transfers.

Figure 2: Importers of major military armaments by region (2)

The cost of conflict to Africa

The massive increase in African weapons spending in recent years suggests that defence companies may be targeting the continent as a last frontier for growth. The costs to Africa are high. A 2007 report by the non-governmental organisation Oxfam International, conservatively estimated that armed conflict cost Africa US$ 18 billion a year and shrank its economic growth by 15%. To contextualise this data, consider that Africa secured US$ 43 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2013 and raised gross domestic product (GDP) by 4.7% in the same year. Thus, it is clear that the economic cost of conflict outpaces Africa’s economic growth.

The failure of many African governments to get to grips with weapons verification, as required by the ATT, suggests there is insufficient political will across the continent to eradicate conflict. However, the major suppliers of arms are equally to blame. Their reticence to sign or ratify the treaty symbolises reluctance to give up the profits and power that weapons trading brings. The inaction of the major arms suppliers, including China, Russia and the US, is a clear indication that conflict in Africa is caused not just by direct participants of war but by the participants in the weapons supply chain that sustains the continent’s many conflicts.

This article is extracted from the May 2014 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM). The essential +-70 page monthly report that dissects conflict developments and trends across the African continent to guide businesses, governments, academics and other stakeholders in Africa’s growth and stability.

Current ACMM subscribers include AFGRI, AngloAmerican, BP, CNN International, eNCA, Halliburton, IBM, KPMG, MSF, various international government departments and major universities around the globe, ranging from UCT here in South Africa to MIT in Boston, USA.

Written by Ingi Salgado (1)

Notes:

(1) Ingi Salgado is the Senior Financial Analyst for ACMM and a Key Consultant with CAI. She also works on financial titles of South Africa’s main newspaper groups and has received various journalism awards for hard-news, feature and opinion articles. Contact Ingi at conflict.terrorism@consultancyafrica.com. ÂÂ Edited by Dominique Gilbert.

(2) Compiled by ACMM with data from ‘Trends in international arms transfers’, 2013, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here