Boko Haram is increasingly emerging as a crucial actor in Nigeria and East Africa. The group has been particularly violent since 2010, and its lethality and its threat to Nigerian and regional stability and security seem to be continuously growing. The recent kidnapping of over 250 girls has attracted extensive international attention and has spawned a social media campaign known on Twitter by the slogan #BringBackOurGirls. In addition, Boko Haram’s continuous attacks and violence have raised questions regarding possible connections with other international terrorist actors such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

This paper analyses the evolution of Boko Haram and its relevance in the Nigerian and regional context. It is worth underlining, however, that a deep comprehension of the group is difficult since little information can be verified and many possible sources of information are unreliable. The first section of this paper briefly examines the main characteristics of the group, its aims and ideology, its membership and its structure. The second section analyses the evolution of the attacks in the last four years, showing some worrying trends. Finally, the last section assesses the relationship of Boko Haram with other terrorist organisations within the region. Growing links between Boko Haram and these organisations could be particularly dangerous both for Nigeria and for the stability and security of the whole region.

Boko Haram: Ideology, membership and structure

This Sunni jihadist group advocates the Islamisation of law and society, to be achieved with the overthrow of Nigeria’s government, which they consider to be composed of false and corrupt Muslims, and the creation of an Islamic state and sharia courts across the country. The leadership of Boko Haram has supported a version of Islam that makes it forbidden (haram) for Muslims to participate in any social or political activity associated with Western society, such as voting in elections or receiving a secular education. The name “Boko Haram”, which can be translated from the local Hausa language into “Western education is sin,”(2) makes clear the group’s rejection of Western culture and principles.(3) However, it is worth noting that Boko Haram does not reject completely the modern world and has successfully employed mobile phones, video cameras, DVDs, and YouTube, showing its ability to exploit the tools of the Western world.(4)

The actual number of Boko Haram’s members is difficult to evaluate because of the elusive character of the organisation, and different estimates proposed by several analysts may reflect different definitions of what constitutes membership. For example, the United States (US) State Department estimates the number of Boko Haram fighters in the hundreds to low thousands, while Nigerian security forces set the number of members at a few hundred.(5) The group shows a high level of heterogeneity with regard to its membership (6) and it is essential to bear in mind that the motivation of individual Boko Haram members may differ greatly from the central organisation’s aims.

The structure of the organisation seems to be extremely fragmented. Boko Haram has never had firm command and control, and the leader Abubakar Shekau is believed to maintain little contact with Boko Haram operatives on the ground and does not seem able to exert complete operational control over its various cells.(7) For this reason, several experts highlight that the group is particularly susceptible to fracturing and to divergences over tactics. Moreover, various operatives may have little understanding of whom they are taking orders from, making their actions more difficult to predict.(8) The lack of a clear leadership can strongly influence the level of violence of the organisation and also has repercussions on the chances to find a diplomatic solution.

Evolution and trends of Boko Haram’s violence

In order to understand the characteristics of Boko Haram, this organisation must be understood as an evolving threat: the group has proved itself to be very adaptable, adopting evolving tactics and changing its targets according to the opportunities. Before 2009 the members of the organisation, which was still headed by Mohammad Yusuf,(9) were not as active as the members of Boko Haram are today. A crucial moment in the evolution of Boko Haram occurred in 2009, when Nigeria police cracked down on Yusuf’s group and violent clashes erupted in reaction in Bauchi, Borno, Yobe and Kano states. Many members fled the region during the 2009-2010 period as a result of the repression by authorities and took shelter in Niger, Chad, Cameroon and, possibly, Algeria.(10)

By mid-2010, Boko Haram returned with a new vigour and became radically more violent and determined, also taking advantage of the training received while in hiding. The new wave of violence included a campaign of bombings, assassinations and attacking police check points. In 2011, Boko Haram militants bombed the police headquarters in Abuja, and two months later carried out a suicide attack against the United Nations (UN) headquarters, killing 23 people and injuring 81 others, which brought the group international attention.(11) Boko Haram’s brutality also increased in 2012, when it carried out its most deadly single day assault, killing around 185 people. The escalation in the level of violence prompted the Nigerian government to declare a state of emergency in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa in May 2013.(12)

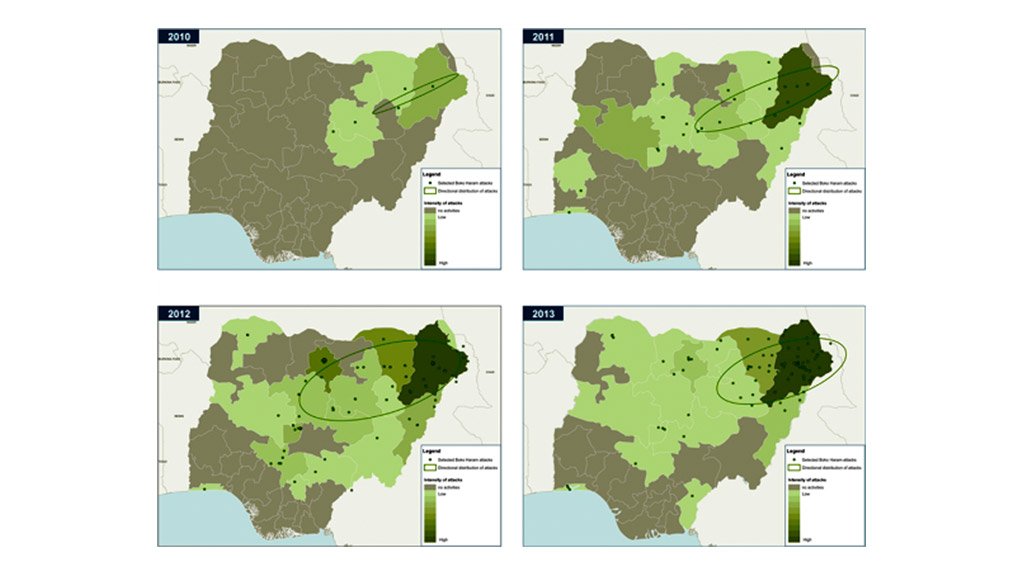

The group’s geographic reach has also expanded since 2009.(13) In 2013, there was an initial contraction in the group's operational reach as a result of the state of emergency and targeted military campaign. However, a more intense frequency and scale of Boko Haram attacks in Borno and Yobe States has been observed.(14)

See Figure 1

Click here to view Boko Haram’s activity evolution(15)

Overall, more than 4,000 people are estimated to have been killed in more than 600 Boko Haram attacks, making Boko Haram one of the deadliest terrorist groups in the world. Boko Haram initially targeted state and federal targets such as police stations and administration buildings. However, the group has increasingly targeted civilians in schools, churches, mosques, markets, bars and villages. In the same vein, local political leaders and moderate Muslims have increasingly been targeted.(16)

The choice of the targets seems to make clear that the group is more interested in a local agenda than on international issues or global jihad. On the whole, looking at the category of targets, Boko Haram has particularly targeted private citizens and property (25% of attacks), police (22%), government targets (11%), religious figures and institutions (10%) and the military (9%). The destruction of churches and targeting of religious figures has often provoked retaliation against Muslim targets, leading to a growing radicalisation. However, attacks attributed to the group have not exclusively, or even primarily, targeted Christians, who are a minority in the north, and the group has yet to conduct attacks against the majority-Christian southern part of the country.(17)

Another worrying trend that can be observed is the growing sophistication and expertise, since 2011, of the weaponry and of the attacks. The group has carried out attacks by way of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), car bombs, and suicide attacks.(18) Boko Haram has not only employed IEDs in its attacks, but also commercial explosives, possibly obtaining the material from central Nigerian mining operations.(19) In addition, the group has proved able to employ a large number of combatants in coordinated attacks: for example, in 2013, groups of 200-300 members of Boko Haram attacked border towns in Borno State using pickup trucks.(20)

Ehe rise in the number of kidnappings is also worth noting. Before the first case of kidnapping in February 2013, this tactic, especially involving foreigners, was almost unused by the organisation. Between February 2013 and June 2013, however, more than 20 kidnappings of Nigerian government officials and civilians, as well as seven foreigners, were performed in Borno. The recent kidnapping of around 270 girls from a Chibok school in southern Borno fits into an escalating campaign aimed, at least in part, at weakening the government’s control over northern Nigeria.

The relations between Boko Haram and other terrorist groups in the region

Ties with other extremist groups could be behind Boko Haram’s growth in confidence, capability and coordination, leading several analysts to consider the influence of other terrorist groups on the escalation of the attacks. A particularly concerning relationship is the one between Boko Haram and AQIM, a regional criminal and terrorist network operating in the Sahel and North Africa.(21) The bombings of a bus station in April 2014 and the abduction of more than 200 schoolgirls in northeast Nigeria seem to testify to a convergence with the modus operandi of AQIM.

There is sufficient evidence to argue that Boko Haram has had a relevant relationship with AQIM in the last three years, although its exact nature is subject to debate. In November 2011, Boko Haram’s official spokesman, Abu Qaqa, stated, “We are together with Al Qaeda. They are promoting the cause of Islam just as we are doing. Therefore they help us in our struggle and we help them, too.”(22) AQIM is believed to have trained members of Boko Haram and the two organisations have likely conducted joint operations in Mali. It is possible that Boko Haram’s increasing ability to conduct sophisticated and coordinated attacks could be originated by the influence of AQIM, as well as its proficiency in employing IEDs.(23) In addition, there has been speculation for years that Boko Haram may have acquired weapons from former Libyan stockpiles through AQIM ties. At the same time, the growing trend of kidnappings by Boko Haram and Ansaru of foreign citizens, started when some members of Boko Haram returned to Borno after the French military intervention in Mali in January 2013, may be an indication of AQIM influence. (24)

In February 2012, The Nigerian Tribune reported that “recently arrested key figures” of Boko Haram had told security agents that while the organisation initially relied on donations from members, its links with AQIM opened it up to more funding from groups in Saudi Arabia and the UK.(25) AQIM training and influence is also reflected in Boko Haram’s use of the internet in to spread violent messages in a manner similar to many Al Qaeda affiliates.

In addition to Boko Haram’s links to AQIM, some members of Boko Haram reportedly may have received training from the Somali terrorist group Al Shabaab in East Africa. For example, Mamman Nur, who is believed to be behind the bombing at the UN headquarters, is supposed to have links to the Somali group, as well as to Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).(26)

However, some experts and analysts are sceptical about considering Boko Haram part of the same global jihadist area as Algeria’s AQIM or Somalia’s Al Shabab. This differentiation seems to be justified, especially considering the target of this organisation and the lack of attacks aimed against Western interests.(27) Furthermore, it is worth taking into account that, to some extent, the link between Boko Haram and international terrorist organisations such as Al Qaeda can at times be played up by several actors such as the Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan with the aim of attracting the help of foreign governments in the fight against the organisation.

Since the organisation is far from being monolithic, it is possible that different factions or splinter groups could develop their own agenda and links with other organisations. In this respect, some Boko Haram leaders could be aiming at building links with “core” Al Qaeda and affiliated organisations, while others remain focused exclusively on a domestic agenda.(28)

Boko Haram has also developed critical links with communities located in the border areas for the purposes of refuge, training, transit and recruitment. For example, Cameroon has become an important centre for recruitment, given the relatively poor majority Muslim northern part of the country and a wealthier majority Christian south. Boko Haram has certainly been able to obtain sophisticated arms and weapons thanks to smuggling operations within and across Nigeria’s borders. For example, man-portable air-defence systems have entered Nigeria through Tuareg smuggling networks in Niger, possibly linked to AQIM. The long and porous borders between Nigeria and Cameroon, Niger, and Chad, often in mountainous areas or in the jungle, have facilitated this activity.(29) In addition, it is worth observing that the movement’s presence in Cameroon, Chad, and Niger is increasing, and these countries have all felt the impact of Boko Haram’s activities, especially with regard to local economies.(30) In this respect, Boko Haram seems to increasingly turn from being a localised problem to a national and regional threat.

Boko Haram: A threat to Nigeria’s stability and a growing regional problem

As the recent attacks and the mass abduction of over 250 girls clearly show, Boko Haram is a growing threat for the stability of Nigeria. In the last four years some worrying trends can be observed, such as an increase in the number of civilians being killed and a growth in the sophistication of the weaponry and of the attacks. However, Boko Haram’s targets seem to make clear that the priority of the group is local: the group has never directly attacked Western countries, except for the case of the UN headquarters in 2011. At the moment, no links with the Al Qaeda core seem to be in place and Al Qaeda has been dismissive of jihadist groups that target Muslim civilians indiscriminately. Nonetheless, Nigeria boasts the world’s fifth largest Muslim population and is thus a long-term priority for the Al Qaeda core.

However, the real risk of Boko Haram could be the evolution of the threat from a local to a regional or global threat. It is likely that several Boko Haram factions have abandoned aims confined to Nigeria and are now embracing regional aims. At the same time, Cameroon, Chad,= and Niger are increasingly affected by the activities of the group. With Nigeria’s general elections approaching in April 2015, the level of violence could increase, undermining stability and security not only in the northeast but also in the whole region.

Written by Diego Cordano (1)

NOTES:

(1) Diego Cordano is a Research Associate at CAI with a research focus on terrorism, insurgency and organised crime in several African regions, especially East Africa and the Maghreb. Contact Diego through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Conflict & Terrorism Unit ( conflict.terrorism@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Nicky Berg. Research Manager: Leigh Hamilton.

(2) The official name of the group is Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'awati wal-Jihad, which in Arabic means "People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad."

(3) Chothia, F., ‘Who are Nigeria’s Boko Haram Islamists?’, BBC Website, 20 May 2014, http://www.bbc.com; ‘Background report: Boko Haram recent attacks’, START National Consortium for the study of terrorism and responses to terrorism website, May 2014, http://www.start.umd.edu.

(4) Walker, A., ‘What is Boko Haram’, United States Institute of Peace Special Report, June 2012, http://www.usip.org.

(5) Oftedal, E., ‘Boko Haram – an overview’, Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, May 2013, http://www.ffi.no.

(6) For more on Boko Haram’s membership, see Sergie, M. and Johnson T., ‘Boko Haram’, Council of Foreign Relations website, May 2014, http://www.cfr.org; ‘Nigeria’s crisis: A threat to the entire country’, The Economist, 29 September 2012, http://www.economist.com; ‘Boko Haram: Growing threat to the U.S. Homeland’, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, September 2013, http://homeland.house.gov; Campbell, J., ‘The different faces of Boko Haram’, Council of Foreign Relations website, August 2013, http://blogs.cfr.org; McGregor, A., ‘Alleged connection between Boko Haram and Nigeria’s Fulani herdsmen could spark a Nigerian civil war’, Terrorism Monitor, The James Foundation, May 2014, http://www.jamestown.org.

(7 The most famous case of a splinter faction is Ansaru, whose emergence in early 2012 contributed to speculation about leadership divisions. Ansaru has been critical of the killing of Nigerian Muslims under Shekau’s leadership and has adopted a more internationally oriented agenda, focusing its attacks on foreigners in Nigeria and neighbouring countries, primarily through kidnappings. Blanchard, L., ‘Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently asked questions’, Congressional Research Service, May 2014, http://fas.org.

(8)‘Boko Haram: Growing threat to the U.S. Homeland’, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, September 2013, http://homeland.house.gov; Blanchard, L., ‘Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently asked questions’, Congressional Research Service, May 2014, http://fas.org.

(9) Founder of Bolo Haram, a Salafis cleric, executed in 2009.

(10) For example, it is believed that the group’s leadership, including Abubakar Shekau, relocated to a hideout in northern Cameroon. Walker, A., ‘What is Boko Haram’, United States Institute of Peace Special Report, June 2012, http://www.usip.org.

(11) National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) website, http://www.start.umd.edu.

(12) Blanchard, L., ‘Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently asked questions’, Congressional Research Service, May 2014, http://fas.org.

(13) In 2009, Boko Haram operated only in north-eastern Borno state, while in 2010 the group expanded its operations to include Plateau state, Bauchi state, and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. By 2011, operations expanded southward to Yobe, Kaduna, Niger, Adamawa, Benue, Delta and Gombe states. In 2012, attacks reached as far west as Sokoto state in the northwest. See, ‘Background report: Boko Haram recent attacks’, START National Consortium for the Study of terrorism and responses to terrorism website, May 2014, http://www.start.umd.edu.

(14) ‘Maps of Boko Haram activity shows group’s evolution’, IHS Pressroom, 20 May 2014, http://press.ihs.com.

(15) Ibid.

(16) Blanchard, L., ‘Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently asked questions’, Congressional Research Service, May 2014, http://fas.org.

(17) ‘Background report: Boko Haram recent attacks’, START National Consortium for the Study of terrorism and responses to terrorism website, May 2014, http://www.start.umd.edu.

(18) Walker, A., ‘What is Boko Haram’, United States Institute of Peace Special Report, June 2012,ÂÂÂ http://www.usip.org.

(19) Stewart, S., ‘Nigeria’s Boko Haram Militants Remain a Regional Threat’, STRATFOR Global Intelligence, January 2012, http://www.stratfor.com.

(20) Zenn, J., ‘Boko Haram’s evolving tactics and alliances in Nigeria’, CTC Sentinel, Combating Terrorism Center, June 2013, https://www.ctc.usma.edu.

(21) The US does not regard Boko Haram as an affiliate with the Al Qaeda core, despite periodic rhetorical pledges of solidarity and support for Al Qaeda.

(22) ‘Boko Haram: Growing threat to the U.S. Homeland’, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, September 2013, http://homeland.house.gov.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Zenn, J., ‘Boko Haram’s evolving tactics and alliances in Nigeria’, CTC Sentinel, Combating Terrorism Center, June 2013, https://www.ctc.usma.edu.

(25) For example, the charity Al-Muntada Trust Fund, with a headquarters in the United Kingdom, has allegedly provided some financial assistance. Boko Haram has also been involved in a wide array of criminal activities which have allowed the group to raise a relevant amount of funds. In addition, donations, daily levies paid by members and extortion have been important sources of funds. In the last two years, kidnappings have gained importance as one of Boko Haram’s main source of funding. See, Oftedal, E., ‘Boko Haram – an overview’, Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, May 2013, http://www.ffi.no; ‘Background report: Boko Haram recent attacks’, START National Consortium for the Study of terrorism and responses to terrorism website, May 2014, http://www.start.umd.edu; ‘Boko Haram’, The American Foreign Policy Council’s World Almanac of Islamism, August 2013, http://almanac.afpc.org.

(26) Zenn, J., ‘Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria’, CTC Sentinel, Combating Terrorism Center, 24 February 2014, https://www.ctc.usma.edu.

(27) Although Boko Haram opposes Western cultures and principles, they have never directly attacked Western countries, with the only exception of the attacks against the UN headquarters in 2011, which, as an isolated event, can be seen as an anomaly.

(28) ‘Boko Haram’, The American Foreign Policy Council’s World Almanac of Islamism, August 2013, http://almanac.afpc.org.

(29) Onuoha, F., ‘Porous borders and Boko Haram’s arms smuggling operations in Nigeria’, Al Jazeera Center for Studies, September 2013, http://studies.aljazeera.net.

(30) ‘Boko Haram: Growing threat to the U.S. Homeland’, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, September 2013, http://homeland.house.gov.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here