The demise of the UDF and popular power: its relevance to recovering our battered freedom

“The popular struggle for democracy has been replaced by a scramble for state posts. This has been but an effect of the ANC’s obsessive concern with ‘attaining state power’ as a pre-condition for democratisation, as opposed to the reverse position - the democratisation of politics and social relations as a prelude to the establishment of a democratic state - which was gradually being developed by the popular movements.” (Michael Neocosmos, “From Peoples’ Politics to State Politics: Aspects of National Liberation in South Africa”, in AO Olukoshi, ed., The Politics of Opposition in South Africa, Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute, 1998: 195- 241).

We are some months into the anniversary year of the UDF with the day of the anniversary celebrated in various cities and towns of the country last month.

Despite this being an attempt at rekindling a spirit that pervaded the UDF and People’s Power in the 1980s, it has not been a period of serious reflection about the meanings of the UDF and People’s Power, the lessons of the UDF for us today, nor of the reasons why the UDF and its manifestations - notably the role of the popular - are no longer an important part, if any, in South African politics today.

If the UDF and Popular Power is an important part of our recent history or of 20th century history and it disappeared, why did it disappear? If it was so important, which I believe is the case, why has it left no trace in current South African political life? And why can we not rekindle - or as the #UDF40 committee says “reignite” - the spirit of the UDF in 2023, a year which is admitted by most people to be a year of multiple crises?

I don't pretend to be the only person who can interpret the meanings of the UDF (insofar as I have distanced myself from the interpretations provided by #UDF40). Nor do I pretend that I understood everything that was happening, or that I did or was able to do anything significant to stop what was happening in the period leading up to the transition and the transition itself, part of the casualties of which was the disappearance of the UDF and the popular manifestations of that period. I did not always understand how best to act in a swift movement from preparing for insurrection to the displacement of the UDF in the period of the MDM in the late 1980s, a Church-Labour arrangement, undertaken in good faith, but lacking the roots in communities that characterised the UDF and People’s Power.

This was the start of a series of changes that were continued in the process of negotiations, which of course, had no connection with popular power, with representatives designated to represent the people, through political parties. They undertook negotiations and “reported back” on complicated processes - acting on behalf of people with whom they had no regular connection of the kind in the mid-1980s People’s Power period.

The political transition moved very quickly, and this was an ANC-led transition, where the ANC was cast as the head of the nation through being destined to head the new democratic nation state.

Michael Neocosmos and Mahmood Mamdani have pointed to this as a pattern on the continent, whereby, as Mamdani says, the victory of national liberation movements entailed the defeat of popular movements. (“State and Civil Society in Contemporary Africa: Reconceptualizing the Birth of State Nationalism and the Defeat of Popular Movements”: Africa Development, Vol. 15, No. 3/4, (1990), pp. 47-70).

What is meant by this statement and elaborated in his article is that the condition for the victory of national liberation movements has tended to be or has always been the rise of a state purporting to represent the people of the country. The nation state becomes the only space to practise politics after national liberation - the state becoming the bearer of nationhood, and affiliates of the UDF and full participants in UDF political practices were consigned to civil society. The notion of a politics of ongoing interaction between constituents and representatives, deriving from and acting primarily within communities, as happened in the popular power period is antithetical to the type of democracy envisaged in negotiations and created in 1994. (See Neocosmos, above).

The popular forces were no longer present on the political stage of history. The organisations through which the popular forces were manifested in the 1980s - civic organisations, youth movements, women's movements, active religious forces, professional bodies and many others - are generally not expected to be key elements in remedying the problems of South Africa. And they are not cast as players in the political sphere, which is the sphere of the state, led by the national liberation movement, in our case the ANC.

The popular movements of the 1980s have no place in the unfolding of this new democracy. The space was ceded to the ANC, and I would not say it was a case of the ANC squeezing out these movements, but also an understanding on the part of many of us in the UDF that we were, as said earlier in this series, the “junior team”. In other words, we were not the leaders of the liberation movement nor the leaders of the popular forces.

Some of us saw or intended to retain the character of the ANC as a popular movement, albeit not cast in the same way as civics, youth and similar movements. This assessment of the ANC may have had some history in the 1950s, and starting afresh in 1990, we thought it could be the basis on which the ANC could be reconstituted as a legal organisation. That was how we understood our task working in ANC Political Education from 1990 up to early 1994 and how we thought or hoped the ANC would develop. But that was not in the minds of most of the leadership.

The ANC was seen as the key to creating a new South Africa, though directly on the ground, especially in the 1980s, the ANC could not be openly present. But it had many of its operatives who played a part both as UDF and as ANC underground, and in other ways acting for the ANC as well as the UDF and within structures of People’s Power.

However, there was this unspoken dichotomy between those who were actually acting and enacting popular power in the 1980s - who were not directly acting as the ANC, located in Lusaka - and then there were the people themselves who created People’s Power. They did this by setting up street committees, popular justice, people's parks and other recreational facilities. These people were in most cases part of the UDF and loyal to the ANC. The structures of People’s Power they created were however, intended to represent and involve the participation of all members of the community, including those who were not part of the “Congress movement” (organisations allied to the ANC and UDF).

As the People’s Power period unfolded, it emerged that there was an uneven embracing or understanding of the often varied conditions and modes of operation of popular power. Some modes of functioning of the UDF were antithetical to the conditions of People’s Power.

In an interview with the late Frans Mohlala, a UDF operative, in 2004, he told me how the Northern Transvaal UDF was de facto banned before the UDF itself was banned. When some of the leaders were arrested at a certain point, they claimed to have only been in X and Y parts of the region, but the police found receipts they had kept, on the instructions of the UDF treasury, and these receipts showed that they had been in a number of other areas and helped sustain the police’s impression that they were “up to no good”. (Interview, Polokwane, 2004).

The UDF rules regarding retaining receipts to buttress claims for expenses were undoubtedly based on sound accounting principles and helped limit the corruption that may have been present then but is now an omnipresent feature of ANC political life. But well intentioned as the rules may have been, they could not coexist with the conditions of operation of some areas where the UDF and organs of People’s Power operated.

Without assigning a date for the demise of UDF and especially People’s Power, it is clear that processes were in motion that led to its snuffing out some time before the 1990 UDF dissolution.

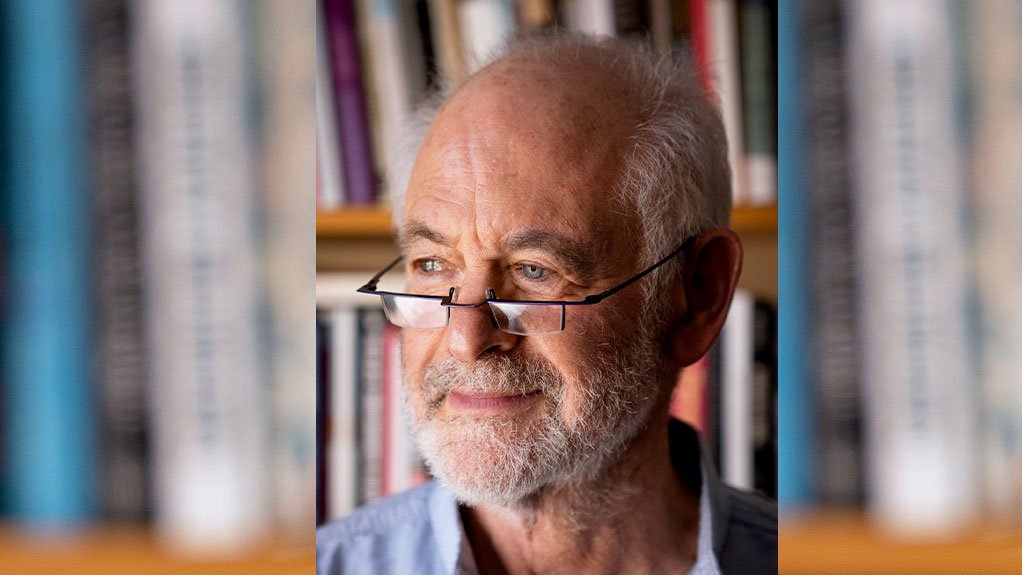

Raymond Suttner is an Emeritus Professor at the University of South Africa and a Research Associate in the English Department at University of the Witwatersrand. He was actively involved in the UDF and in advocating People’s Power. This led to his spending much of the 1980s underground, in State of Emergency detention or under house arrest. He is a former member of the national leadership of the ANC and SACP, from which organisations he severed links at the time of the rise of Jacob Zuma to leadership.

This article is the fifth in a series on the 40th anniversary of the UDF. Read the other articles in the series here.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here