![]() South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown is likely to have a devastating impact on the incomes of workers and their dependants. There is broad agreement that the lockdown is a necessary public health response. But the economic damage that it will do to the poor needs to be addressed urgently.

South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown is likely to have a devastating impact on the incomes of workers and their dependants. There is broad agreement that the lockdown is a necessary public health response. But the economic damage that it will do to the poor needs to be addressed urgently.

We project that, in the absence of an intervention targeted at vulnerable households, the extreme poverty rate among these households will almost triple.

Fortunately, the South African state has access to a vast social grant infrastructure that allows it to immediately reach most of the poorest households. The country already distributes 18-million grants every month and 12.5-million of these are child support grants.

To support precarious households that are unable to access existing relief during this lockdown and its aftermath, the South African government should implement a temporary increase – a “top-up” – in the value of the existing child support grant.

The relief measures announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa are mostly aimed at supporting South African households by expanding unemployment insurance via the Unemployment Insurance Fund, and by offering relief to tax-registered businesses.

However, based on our own calculations we estimate that about 45% of South African workers are not eligible for relief from the fund. Under existing measures, nearly 8-million workers, and the 13-million additional household members whom they support, will be left without relief.

Across the world governments have taken extraordinary actions to support workers and households during the COVID-19 pandemic. They have done so because they recognise that these actions are necessary to prevent an even more catastrophic economic and humanitarian crisis.

Some 84 countries have implemented social protection programmes, a third of which rely on cash grants. They include Brazil and China.

South Africa should use its own existing social grant infrastructure to similarly protect vulnerable households. Supporting informal workers directly through unemployment benefits or new targeted grants would be extremely difficult. These workers are unregistered, untaxed and undocumented. A substantial top-up of the child support grant would put money directly into the hands of the hardest-hit households. It could do so immediately.

Who would benefit from a top-up

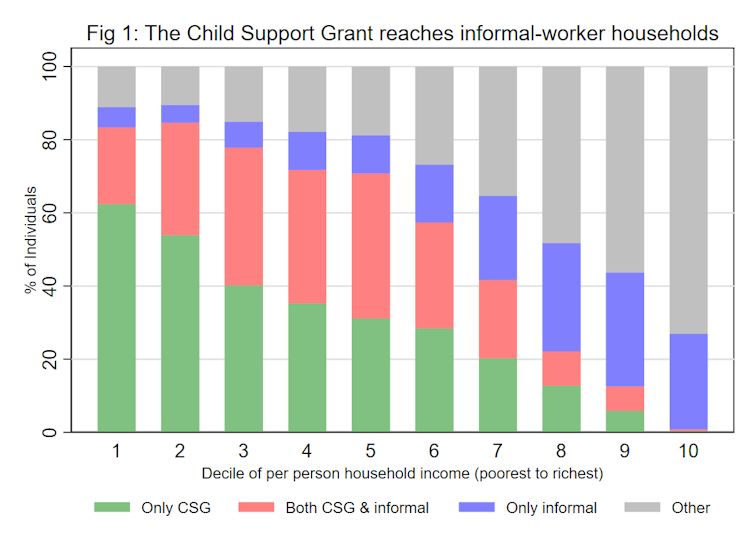

The child support grant reaches households that are not covered by existing relief. Using household survey data from the 2017 National Income Dynamics Study, we show in the graphic below (Figure 1) the percentage of individuals who are in a household that:

1) has a child support grant recipient but no informal workers (green bars),

2) has both a child support grant recipient and an informal worker (red bars),

3) has an informal worker but no child support grant recipient (blue bars) and

4) has neither a child support grant recipient nor an informal worker (grey bars).

Each bar then shows these percentages by income decile, with the poorest individuals on the left and the richest on the right.

The figure shows that in the poorest half of the population, the child support grant reaches 80% of individuals who are in informal worker households (the red bars are much bigger than the blue bars).

Additionally, the child grant benefits poor individuals the most and is well targeted to the most vulnerable. Of course the grant does not reach all informal-worker households. Many people who are on the edge of poverty are not covered by the grant and remain vulnerable.

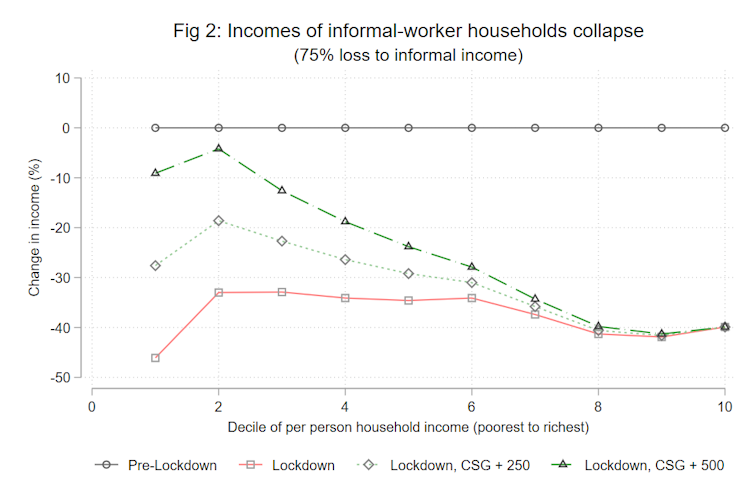

We can also directly see how topping up the child grant will help those worst affected by the lockdown. Since the lockdown will last for an initial three weeks, we assume that workers who are not eligible for Unemployment Insurance Fund benefits will lose 75% of their monthly income.

The graphic below (Figure 2) shows the percentage changes in shared household incomes under various scenarios, but only for individuals who are in households that contain an informal worker. The red line shows the loss in income compared with the pre-lockdown scenario (black line). As can be seen from the figure, for the bottom six deciles we project about a 33% loss in per-person household incomes as informal incomes collapse.

An increase to the child grant will partially compensate the most vulnerable for this loss in income (green lines). For example, for the poorest 10% of individuals, we estimate that per-person household income will decrease by 45%. If a child grant top-up of R500 is implemented, this fall in incomes is much less – now only 10% less than pre-lockdown incomes.

Without a top-up, the projected loss in income will result in a devastating increase in poverty and food insecurity.

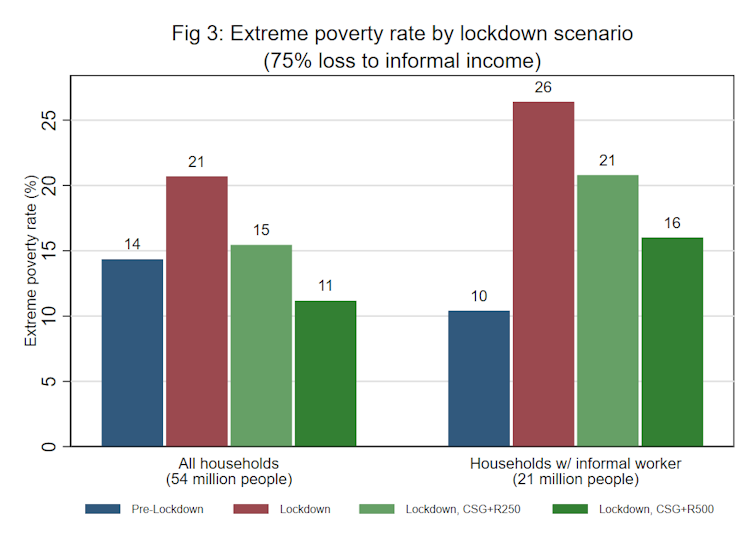

The last graphic (Figure 3) shows the projected changes in the rate of extreme poverty – the percentage of individuals with per person household income less than R580 per month – depending on what interventions are imposed. The four bars on the left of Figure 3 show the extreme poverty rate when looking at all South Africans. The four bars on the right show extreme poverty among individuals who have an informal worker in their households, in total, 21-million people.

The first two columns of Figure 3 show that the lockdown could lead to a 50% increase in the national rate of extreme poverty (seven percentage points). This means that an additional four-million South Africans will be unable to afford enough food. For individuals in households that rely on income from informal work, the rate of extreme poverty will almost triple, from 10% to 26%. But as the green bars in Figure 3 show, a temporary top-up to the child support grant would immediately mitigate the impact on extreme poverty, with larger top-ups working better.

A top-up of R500 per month would reduce the national extreme poverty rate compared to pre-lockdown levels, while for those in informal-worker households the extreme poverty rate increases by just six percentage points, rather than 16 percentage points. A top-up of R250 per month, while certainly an improvement over the status quo, is not nearly as effective for informal-worker households.

Throughout this analysis we have assumed that the incomes of workers registered under the Unemployment Insurance Fund will not decrease during the lockdown. But with millions of workers likely to apply simultaneously, we might expect delays in payouts and other gaps in coverage. Any gaps only strengthen the case for topping up the child grant because it is well targeted to vulnerable households.

Action is imperative

While the lockdown may be a necessary measure, the South African government should use the tools that it has to mitigate the immense human suffering that the associated economic deprivation will cause. We estimate that increasing the child grant by R500 (per month) will cost the fiscus approximately R6.2-billion per month, which is certainly not a prohibitive cost.

An increase in the child grant would reach those especially vulnerable to the effects of the lockdown. It can be implemented immediately with the sophisticated infrastructure that already exists. And it would disproportionately benefit the poorest households. It would be a tragedy if the South African government chose to ignore such an achievable and effective policy option.

Written by Ihsaan Bassier, Phd candidate in Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Joshua Budlender, PhD candidate in Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Murray Leibbrandt, Pro-Vice Chancellor, Poverty and Inequality; NRF Chair in Poverty and Inequality Research; and Director of the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town; Rocco Zizzamia, DPhil candidate, International Development, University of Oxford, and Vimal Ranchhod, Professor, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here