Nigeria is set to hold presidential elections in 2015. These elections are likely to be heavily contested, as evidenced by the recent, temporary arrest of the key opposition leader Nasir el-Rufai over comments he made about the likelihood of violence during the election.(2) These elections also appear to be an increasing source of pressure on the current president, Goodluck Jonathan, who faces collapsing support amongst his own political party and backers, over the, as yet unanswered, question of whether he will compete in the 2015 elections, exemplified by recent mass defections from his own political party, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The PDP has been dominant in the country’s elections since 1999, but now appears substantially weakened by infighting and factionalisation.(3) Jonathan is also struggling to maintain the delicate balance of ethnic, religious and political alliances and appointments which had previously secured his presidency.

This article is extracted from the March 2014 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM) – the brainchild of award-winning journalist and columnist, James Hall. The +-70 page report dissects conflict trends across the African continent to guide businesses, governments, academics and other stakeholders in Africa’s growth and stability. Click here to find out more about ACMM.

The Nigerian political environment has been characterised by high levels of inter-ethnic or inter-tribal tension since the country achieved independence in 1960. The devastating 1967-1970 civil war, and a succession of military governments, has created an underlying attitude of ‘winner takes all’ that continues to overshadow Nigeria’s troubled relationship with democracy. Jonathan’s ascension to the presidency in the aftermath of the death, in office, of President Umaru Yar'Adua in 2010 was heavily influenced by the fact that Jonathan is an ethnic Ijaw. The Ijaw are a minority group from the Niger Delta region and as such, Jonathan was considered a satisfactory compromise to both the Hausa-Fulani and Yoruba ethnic majorities who have traditionally competed for control of the country.

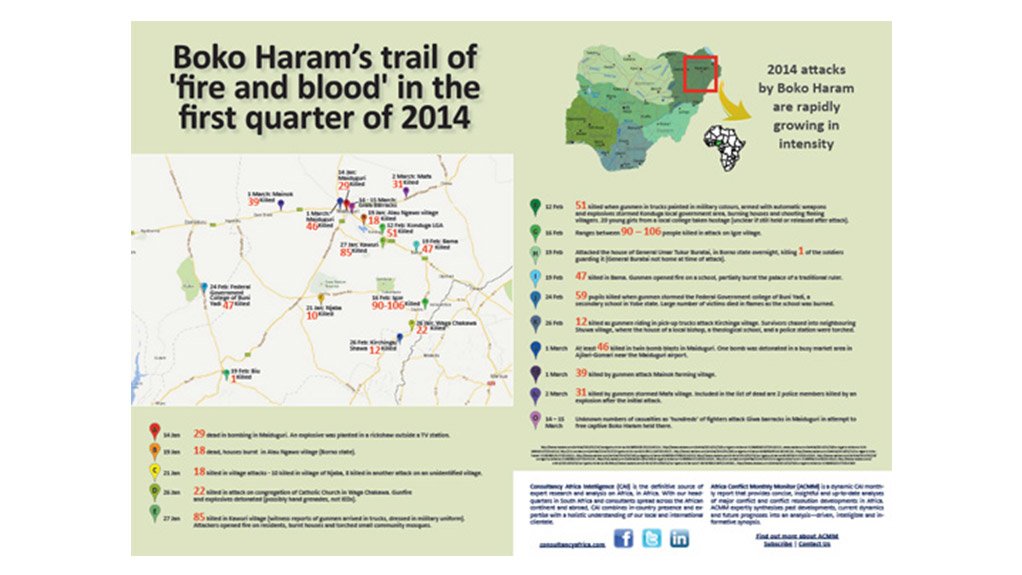

Nigeria has faced numerous internal security and stability threats since independence, particularly in terms of crises arising out of inter-ethnic or inter-tribal antagonism. The attempted secession of ‘Biafra’ by Igbo separatists (an ethnic minority concentrated in the south-east of the country) led to the 1967 Civil War. More recently, Ijaw dissatisfaction at political and economic marginalisation by the Abuja-based government led to protracted outbreaks of violence in the Niger Delta – the source of Nigeria’s oil wealth – from the mid-1990s until a tenuous ceasefire in 2009. However, for Jonathan, the overwhelmingly dominant security threat of his presidency has been the rise of Boko Haram. This militant Islamist sect was first formed in 2002 but, since 2009, has grown increasingly violent. The continued conflict in north-eastern Nigeria where Boko Haram operates is a major source of insecurity, and a significant blemish on Jonathan’s political record. Perhaps with the 2015 elections in mind, Jonathan has attempted to decisively end the uprising, announcing a State of Emergency in certain key states in north-eastern Nigeria in May 2013 as a pre-cursor for a military crackdown and outright offensive against Boko Haram urban strongholds. Despite numerous claims of substantial successes by the military, this offensive has failed to eradicate Boko Haram. Going into 2014, the group has shown that it is not only still capable of terrorist attacks, but also willing and able to directly confront the Nigerian military itself.

In an effort to address the disintegrating political situation in Abuja, as well as the violence in the north-east of the country, Jonathan has resorted to reshuffling both his cabinet and his military command structure. Major reshuffles occurred in late 2013, and then again in February 2014, seeing an entirely new military command structure, as well as new cabinet positions. It also appears that Jonathan is actively attempting to revitalise his flagging ground-level support. A notable example of this is a recent presidential signing-into-law of a bill which criminalises same-sex relationships.(4) While gay and lesbian tolerance is low in Nigeria, as with many African countries, the signing of this law, which had sat on the president’s desk awaiting confirmation since May 2013, is indicative of the pressure on the president. This move has resulted in significant criticism from the international community from which Jonathan has previously made efforts to garner support. Such measures, which sacrifice international support for local favour, are indicative of the prioritisation of the 2015 election.

Countering the rise of Islamist militancy has overshadowed the Jonathan administration

Jonathan’s presidency has been dominated by the counter-insurgency campaign being fought against Boko Haram. This group, since its early formation in 2002, has undergone several stages of evolution, both strategically and tactically. The group dramatically escalated its violence after the 2009 death in police custody of its original leader, Mohammed Yusuf. Boko Haram has embarked on a campaign of terrorist attacks designed to weaken the Nigerian Federal Government, through direct attacks, and also through inflaming pre-existing inter-ethnic tensions. Nigeria’s longstanding sectarian clashes between the predominantly Christian south and the Muslim north has played out in Central Nigeria, and has been exacerbated by Boko Haram attacks on Christian targets. Critics of the group, such as the media and the Muslim community itself, have also been targeted. The group has also periodically targeted banks or prisons holding captured members, in order to finance and continue the fight.

The Jonathan government, as with the previous government of President Umaru Yar'Adua, has tried several means of countering Boko Haram. Initial efforts included downplaying the group – describing many of the early attacks as either criminal attacks, or extensions of sectarian conflict. In both cases this is true to an extent, but these attacks were nonetheless ostensibly the work of Boko Haram. The frequency and nature of the attacks grew – particularly as motorcycle drive-by shootings gave way to increasingly sophisticated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and outright large scale ground assaults on villages and military bases. Consequently, the Nigerian government finally began to acknowledge the extent of the security threat it faced.

The following ACMM infographic tracks Boko Haram's trail of violence across north-eastern Nigeria in the early months of 2014:

Click here to download / view the infographic (PDF)

The Jonathan government has also attempted negotiations with Boko Haram in hopes of achieving a similar peace to what was achieved previously in the Niger Delta region in the south of the country. There the leadership of militants fighting under the banner of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) was effectively bought off with promises of amnesty and pensions or access to lucrative government contracts. These bribes were ostensibly part of a broader promise of greater inclusion in the political and economic dealings of the country. However, such promises, made either tacitly or overtly to Boko Haram, did not achieve the same effect. Boko Haram expresses an extremist or fundamentalist set of goals of seeking to replace the Federal Government with an Islamic one, as well as installing Sharia (Islam-based) law. Considering the nature of the group itself, it is little wonder that negotiations have not been possible. Boko Haram has a highly secretive leadership structure and often appears more of an umbrella organisation to multiple groups, rather than one unified force. Moreover, as a result, negotiations have only been considered likely to succeed with substantial leverage first being achieved by the Nigerian government.

The Nigerian military has pursued that leverage, although it has often appeared bent on the total eradication of the group. The Joint Task Force (JTF), a specially formed military and security force previously tasked with adding military pressure to compel MEND to attend the negotiations table, has been responsible for a particularly violent counter-insurgency campaign against Boko Haram in its urban strongholds in north-eastern Nigeria. The JTF’s campaign has been characterised with allegations of extra-judicial detentions, torture, and extra-judicial executions by human rights groups such as Amnesty International (AI) and Human Rights Watch (HRW). In May 2013, the military-centric approach of countering Boko Haram was further emphasised with the declaration of a State of Emergency in three states in Northern Nigeria, specifically Adamawa, Borno and Yobe. The resulting military crackdown saw a major offensive launched against Boko Haram’s urban strongholds by newly designated military formations that took over from the JTF. This offensive succeeded in pushing Boko Haram out of cities in the north-east of the country, or at least disrupted their previous strongly held positions.

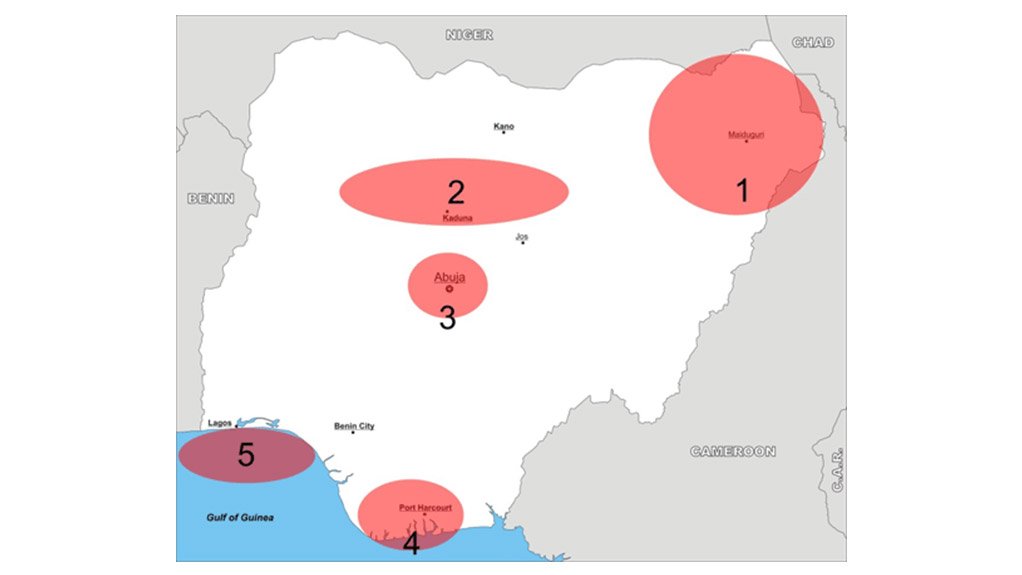

Fig 2: Keeping security forces vigilant: Nigeria’s hotspots (5)

Failure to secure the north-east of the country adds to political pressure on Jonathan

The military crackdown has, however, not succeeded in either eradicating the group or in forcing it to the negotiations table. If anything, the military-centric approach has worsened the situation. Substantial civilian deaths have occurred, according to human rights groups, while Boko Haram has not only retained the ability to conduct terror attacks, but has also shown itself capable and willing to directly attack military and security forces.(6) Reports on the specifics of the fighting are unclear and obscured by a lack of media access. Reports are also heavily twisted by biased Nigerian military announcements which invariably claim to have inflicted substantial losses on Boko Haram with minimal, if any casualties to their own troops in the aftermath of each bout of fighting.

International commentators and media have questioned the Nigerian military’s account of the fighting in north-eastern Nigeria, but the behaviour of the military itself is increasingly evident of the failure of the military counter-insurgency campaign. The senior leadership positions of the military have been substantially reshuffled in recent months. Moreover, the newly promoted leadership in charge of the campaign against Boko Haram has backtracked on calls made in early 2014 to end the insurgency by April. Recent ‘clarification’ by military spokesmen suggests that these calls were not intended to be taken literally.(7)

The failure to quell the Boko Haram threat and, indeed, the possibility that the military approach taken thus far has worsened the situation has provided significant fodder for President Jonathan’s political critics. Other criticism has arisen, as Jonathan’s position is increasingly judged to be weakened. Even his previous benefactor and mentor, former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, wrote a series of public letters to Jonathan that criticised Jonathan’s presidency and argued that he should not run for re-election in 2015.

It is worth noting that Jonathan has faced several domestic crises previously. A notable example involves his efforts to reform fuel subsidy initiatives that had been put into place by previous governments. Jonathan removed those fuel subsidies in January 2012, arguing that they were a source of corruption and cost the country in revenues which could be directed at infrastructural development. Nigerians, many of whom see low petrol costs as one of the few benefits of the local oil industry which actually reaches them, disagreed – violently. Widespread protests erupted to the extent that Jonathan had to quickly back down, and reinstate the subsidies. Another source of pressure has been maintaining the fragile peace in the Niger Delta region. This troubled area is the source of Nigeria’s oil wealth, but is also closely tied to multiple security and stability issues, in the form of MEND, as well as a black-market which has sprung up around the practice of oil-bunkering. This practice involves the theft of crude oil from pipelines and tankers. Additionally, the area has experienced increasing instances of maritime piracy, which initially targeted at the oil industry which stretches into the Gulf of Guinea. In response, Nigeria’s navy has become increasingly active in counter-piracy efforts, while the JTF is once again active in the Niger Delta region, targeting oil thieves. Another, persistent, stability trouble-spot is the central band of Nigeria, where inter-ethnic conflict plays out between pastoralist and agrarian groups, who also tend to identify as Muslims and Christians respectively.

Any president of Nigeria will invariably face a range of crises which threaten the peace and stability of the country, but winning re-election is arguably more difficult. President Jonathan knows that if he is to compete in the 2015 election, he must find a way to end the violence in north-eastern Nigeria, and must also take decisive steps to return his own political house to order. It appears that the possible outcome of the election will be decided in the coming months, and will depend on whether Jonathan can stop the hemorrhaging of PDP members, and successfully reconstitute a sufficiently representative cabinet. Moreover, Jonathan must find a way to facilitate a militarily effective command structure capable of dealing with Boko Haram, while also ensuring the loyalty of the command which, historically, has been the biggest threat to Nigeria’s democracy.

This article is extracted from the March 2014 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM) – the brainchild of award-winning journalist and columnist, James Hall. The +-70 page report dissects conflict trends across the African continent to guide businesses, governments, academics and other stakeholders in Africa’s growth and stability. Find out more about ACMM.

Written by Conway Waddington (1)

Note from the author: This article is a follow up to the previous (Feb 2014) article, which cast doubt on the veracity of the narrative being portrayed by Nigerian military spokesmen regarding counter-insurgency campaign successes against Boko Haram in north- eastern Nigeria. This article examines the mounting political pressure on President Goodluck Jonathan.

Notes:

(1) Conway Waddington is a Regional Analyst with ACMM, has contributed papers, reviews and conference material to the Institute for Security Studies (Pretoria, South Africa) and has acted as a peer-reviewer for Scientia Militaria. Contact Conway through CAI’s Conflict & Terrorism unit ( conflict.terrorism@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Dominique Gilbert.

(2) Eboh, C., 'Nigeria security service arrests deputy opposition leader', Reuters, 27 January 2014.

(3) 'Nigerian PDP senators in mass defection to APC', BBC News Africa, 29 January 2014.

(4) Onuah, F., 'Nigerian leader signs anti-gay law, drawing US fire', Reuters, 13 January 2014.

(5) Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Medina Dauda

(6) Map compiled by ACMM with data from D.Maps

(7) 'Nigeria Boko Haram emergency: “More than 1,200 killed”', BBC News Africa, 16 December 2013.

(8) 'Boko Haram “deadline” not literal: Nigerian military', AFP, 5 February 2014.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here