The outpouring of anger and calls for President Jacob Zuma to step down, although occasioned by the Constitutional Court judgment on Nkandla, are in fact a result of rage that has been building up for many years. We need to try to understand the significance of this moment and how it will define the future.

We have been here before. One thinks of the rise of public opposition to former President Thabo Mbeki after the dismissal of Zuma as Deputy President in 2005. This led to people burning t-shirts bearing Mbeki’s image and a growing opposition to his rule. As we know, that opposition culminated in Zuma’s election as president of the ANC and the state.

Zuma’s supporters promoted his candidature with qualities that would remedy some of the ills attributed to the Mbeki era, in particular centralisation of decision-making, a lack of empathy for ordinary people on the ground, and an absence of popular influence on policies. His supporters said Zuma was humble, a “good listener” and an inclusive and democratic leader with deep commitment to non-racialism.

He was depicted as a leader who understood the specific left objections to the Mbeki era, in particular its macroeconomic policy known as GEAR. It was claimed that Zuma was the embodiment of the popular and even a potential leader of a socialist project. This was despite their knowing very well that Zuma, like Mbeki, had withdrawn from the SACP in 1990 and, while in government, had raised no objections to Mbeki’s policies. Both COSATU and SACP leaders of the time advanced this leadership imagery.

Much was made of his humble origins. He was said also to be a model of advancement that would inspire others from similar poor backgrounds; a variant of the “American dream” where any person is supposed to be able to rise to the top.

Some activists, despite long political experience, spoke of the rise of Zuma setting South African democracy free. A new dawn was about to rise under Zuma. Even business, although cautious, was willing to give him a chance.

It is important to look back to that moment when Zuma was advanced as a candidate, for the terms on which he was advanced do not correspond to what he has in fact delivered as president of the ANC and the country. Some of the reasons why this could not be so were, as indicated, already known before he became president

As South Africans call for Zuma to step down, we must be mindful of the errors of the past. We need to be clear that Zuma’s unsuitability for office does not arise only from the Constitutional Court judgement on Nkandla. There is a range of fundamental problems with his leadership and these must be spelt out so that there is no ambiguity on what needs to be resolved, how it should be done and by whom. This will go a long way to ensure that if we move towards choosing a new leadership, we “buy” what we think we are buying, not something different, as was the case with the disparity between claims for Zuma and the actual “product”, which currently creates havoc in South African public life.

In consequence, we need to ask what is the objective behind the calls for Zuma to step down. Expressions of righteous anger over Zuma’s actions and the call for him to resign must be coupled with clarity over the goal to which it is directed. How does it bear on the post-Zuma period? If the goal is to remove Zuma, what is envisaged to follow? If Zuma is to be removed in order to set the country on a democratic course, retrieving and even enhancing what has been undermined, we need to ensure that we have a common understanding of the problems, the processes of addressing them and the outcome that is sought. That means identifying precisely what the defects of the present have been and what is needed to ensure that what is put in place after Zuma’s departure is a remedy and not a variant of the attacks on democracy that characterise current ANC-led political life. If there is not that clarity, what is currently experienced could well re-emerge under a different aegis.

That this question –“what follows Zuma”? -needs to be asked is warranted when we consider, in addition, that many of those who are associated with the call for Zuma to go had no objections to him becoming president. Some served under him in one or other capacity - or left in ignominy. Others served under Zuma and raised no objections to the character of his political activity prior to his elevation to the presidency. Yet others held no position, but saw the rise of Zuma as unproblematic. The object of this reference to the political history of some signatories or people who have provided testimony is not to vilify them but to seek clarity on the terms in which various actors are engaging with the removal of Zuma.

How one has related to the conduct of Zuma in the past is relevant to the present and the future. It is very important how one related to this political phenomenon, which needs now to be eradicated because of its fundamentally anti-democratic character. That some have to this day never accepted or argued over whether it is correct to characterise the Zuma period as anti-democratic is very relevant if these are people to whom some may turn for counsel or leadership in the post-Zuma era.

That these questions must be asked relates to the contention of this article that the flaws in Zuma’s political character and actions were not unknown before the Nkandla scandal. They were in fact features that threatened democratic life and constitutionalism long before he became president and were especially evident in the period immediately prior to his election as ANC and state president. I refer in particular to the 783 corruption and fraud charges that Zuma faced until the last moments before his inauguration (which may now have been reinstated) and his conduct during his rape trial. I refer also to the conduct of the ANC under his leadership during the 2009 elections, notably the political intolerance towards COPE, with violent interruption of meetings, preventing COPE from pursuing its right to free political activity.

In other words, the reasons for Zuma’s removal now do not constitute revelations about his fitness or otherwise to hold the office of president or to have a place in public life in a democratic South Africa. These patterns of conduct were fairly well known and certainly so to those who worked with him in the ANC of the 1990s and early 21st century. Some say many of these qualities were evident in exile.

If many of those calling for his removal were well aware of his flaws and have chosen now to focus almost exclusively on his being legally compromised over Nkandla, it raises questions about how those who call for his removal conceive the reasons for removing him. Does this not leave room for replacing Zuma with someone who may well bear some of the weaknesses and dangers that were part of Zuma’s make up and have not been raised as objectionable. It certainly leaves opaque how those calling for Zuma’s removal conceive the question of patronage and even some further forms of corruption not addressed in the Public Protector’s report on Nkandla.

How do they view the use of violence and militarism, the deployment of static forms of culture and cultural chauvinism to stifle debate and limit the freedom of some citizens? How do they see displays of hyper patriarchy, high tolerance of sexism and finally the abuse of the symbols of the liberation struggle, its songs and meanings, to serve his personal interests, as in his rape trial?

To what extent are these statements and protests against Zuma understood as being part of a “cleansing” of the ANC, part of a return to “glorious values” attributed to the ANC?

The assumption in many of the protests and petitions is that there was an ANC of the past to whose traditions we must return. To what extent should we endorse the objective of many petitions to return the ANC to its former glory? Should we not in fact be interrogating the character of the ANC now and earlier, for it is the organisation that has made it possible for Jacob Zuma to emerge as its leader?

Those of us who have had a long history in the ANC, need to ask whether we understood the organisation in all its manifestations, even if we were innocent of some of the abuses that are now known to have taken place? Should not all of us who have been involved in the ANC ask what part we played in creating an organisation that allowed the rise of a lawless president who is antagonistic to democratic life and emancipation?

Should the call for Zuma’s removal not be part of a broader plan to restore democratic rule under the constitution? Should it not be part of the regeneration of democratic life to encourage the emergence of other political formations, whether or not they directly challenge the ANC?? If that is the case, there is no guarantee that the ANC will continue to enjoy its previous pre-eminent status.

If we are reviving and enriching an ongoing process of emancipation, we cannot rely on a return to the ANC’s past. Nor can we exclude options beyond the ANC. Those who believe in liberatory and emancipatory values cannot exclude the ANC as a potential home, but we are entitled to scepticism and to explore all options that may enrich and consolidate our democratic life.

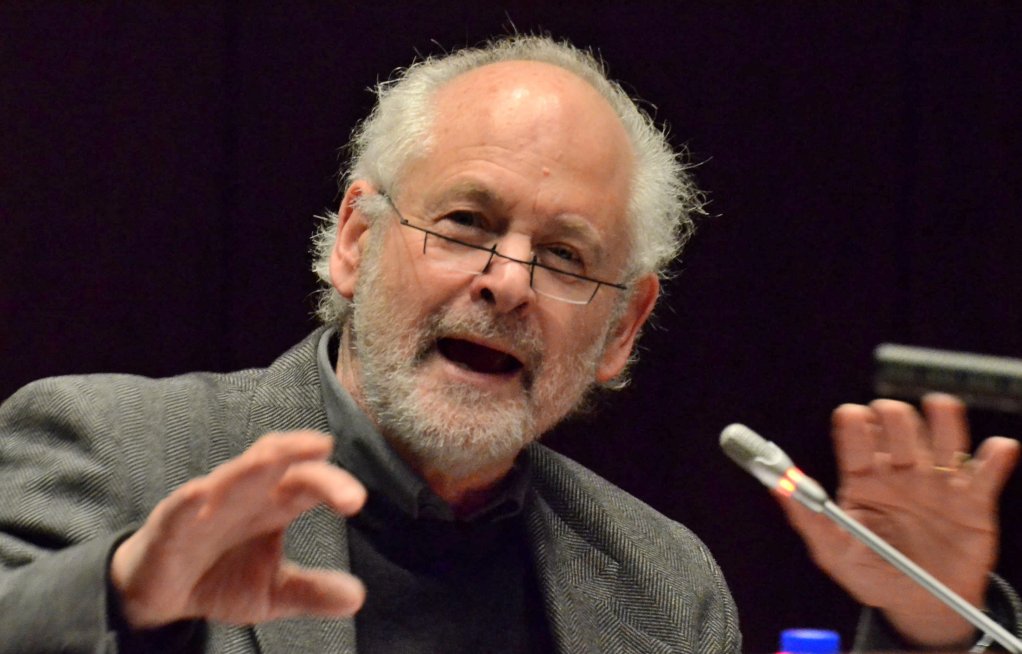

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. Much of his life was spent in the struggle against apartheid and in building the new democratic order. He served lengthy periods as a political prisoner and under house arrest. Currently he is a professor attached to Rhodes University and UNISA and he has authored or co-authored Inside Apartheid’s Prison (2001), 30 Years of the Freedom Charter (1986) 50 Years of the Freedom Charter (2006), The ANC Underground (2008) and most recently Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana and Lynne Rienner, 2015). He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here