JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – Platinum group metals (PGMs), which South Africa hosts in greater abundance than any other country on earth, are playing important catalytic roles in Switzerland’s green hydrogen and green truck rollout, which is now under way.

Mining Weekly can today report that proton exchange membrane (PEM) technology, which benefits from catalysis brought about by PGMs in both electrolysers and fuel cells, is the technology of choice and is helping to bring about an incipient green hydrogen ecosystem in Switzerland. PEM electrolysers are generating the green hydrogen that is so critical in the road-tax exemption that is rendering the use of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) an economic proposition.

“With the PEM, we have a lot of advantages,” Hyundai Hydrogen Mobility CEO Mark Freymueller told Mining Weekly in a Zoom interview. (Also watch attached Creamer Media video.)

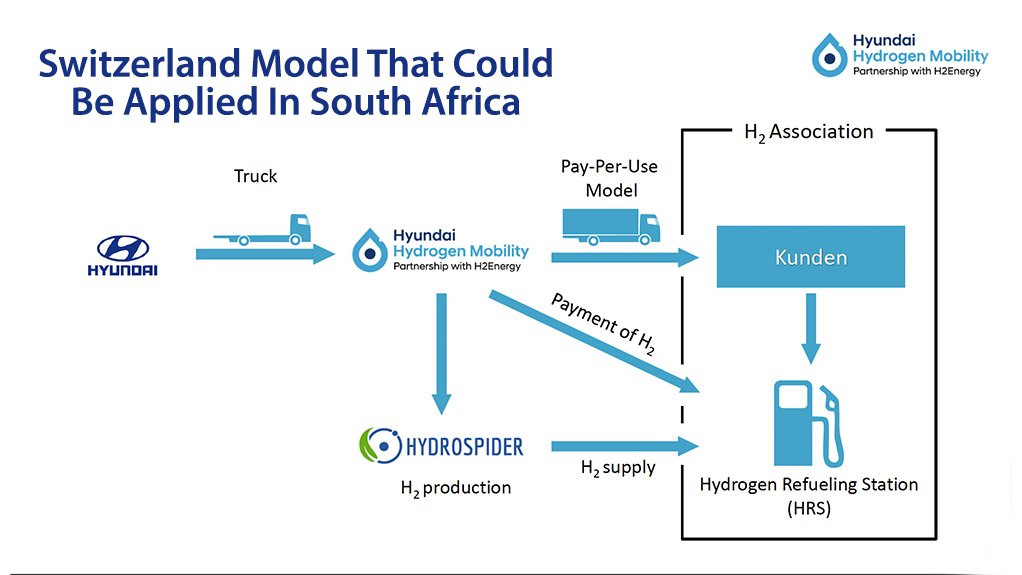

The advantages centre on the production of the green hydrogen, which is being undertaken as part of the Hyundai Hydrogen Mobility joint venture by Hydrospider, a joint venture between Linde, which is well known in South Africa, Alpiq and H2 Energy. (See attached graphic.)

The choice of PGM-catalysed PEM electrolysers are the result of their greater operational flexibility: “You can turn them on and turn them off more quickly,” Freymueller said.

This flexibility facilitates access to cheaper electricity, which in the case of Switzerland can be environmentally friendly hydropower, when it is available on the grid. Fifty six per cent of Switzerland’s electricity is hydropower.

“This is in 15-minute frequencies, so it’s more flexible from a usage perspective,” Freymueller explained.

“What’s important to understand is that we’re not just looking at a demo project here. We have a market launch of fuel cell hydrogen trucks. It’s not just one truck here and another truck there.

“We have already 50 fuel cell trucks in the market and our plan is to have another 1 000 in just Switzerland by 2023, and then 1 600 by 2025,” said Freymueller.

The truck model in question is the Xcient, the world’s first mass-produced heavy-duty fuel cell truck. These left-hand-drive FCEVs are well suited to commercial transport because of their ability to cover long distances and refuel in a matter of minutes. These FCEVs, which generate absolutely zero emissions, have at their heart 190 kW platinum-catalysed fuel cells that enable them to haul a 36 t truck-trailer combination over a distance of up to 400 km on a single refill.

Switzerland’s waiving of heavy-duty road taxes on zero-emission vehicles has helped to make a business case for the users of the Xcients, on which no initial investment has to be paid.

Hyundai Hydrogen Mobility rents them on a pay-per-use basis, which involves the customer paying an all-inclusive per-kilometre amount that covers the cost of the hydrogen.

“We’re not producing the hydrogen ourselves and we’re not building up the infrastructure by ourselves, but we’re basically coordinating everything,” said Freymueller. This coordination is with business partner Hydrospider, for the hydrogen, and different members of the hydrogen association operating fuelling stations.

15 TRUCKS EQUIVALENT TO 700 CARS

On trucks coming ahead of cars, Freymueller explained that both trucks and passenger cars need one another to develop, with trucks the initial low-volume infrastructure supporters and cars contributing the high volumes over time.

A hydrogen fuelling station needs to gain, over a ten-year depreciation period, about €190 000 to €200 000 through the sale of 95 t of hydrogen a year.

“You can either do that with about 700 passenger cars or you do the same thing with 15 trucks. That is the big difference because there are barely 700 hydrogen passenger cars all over Europe. They would have to refuel at this one refuelling station to make a financially viable business case for the refuelling station.

“But 15 trucks is relatively easy to coordinate around this refuelling and that is just because the passenger cars have less mileage and less consumption and the demand of the truck for hydrogen is much higher so the throughput of hydrogen is much higher on the trucking side.

“Then, once the infrastructure has been built for the trucks, it can also be used to refuel passenger cars. So, trucks are the right thing to start with and the passenger cars can follow and bring the scalability,” Freymueller explained.

GREEN HYDROGEN

Switzerland’s entry into the hydrogen economy is based on the use of green hydrogen.

“We’re focusing completely on green hydrogen, not only because it is the right thing to do, but also because otherwise it would just be a relocation of exhaust pipe emissions to somewhere else.

The business case works because diesel costs are higher in Switzerland than in other European countries and, more importantly, the exemption of emission-free vehicles from road tax.

“This road tax is directly connected to the weight of the vehicle and the annual mileage, so the heavier the vehicle is and the more kilometres the vehicle is doing, the higher the road taxes and we’re talking about quite a significant amount of about €60 000 per truck per year.

“This tax, and also all other subsidies, is basically to reduce the carbon dioxide (CO2) footprint. If the CO2 is just produced somewhere else and only the local vehicle operation is CO2-free, then at some point in time the government will say, ‘wait a second, you’re not really CO2-free so you have to pay the tax’, and that would jeopardise the whole business case.

“Also, in the long-run, there are a couple of studies that clearly state that green hydrogen will be cheaper than grey or blue hydrogen anyway, and from a purity perspective, green hydrogen has a lot of advantages,” said Freymueller.

The climate-friendly hydrogen value chain relies on solar systems, wind farms or hydropower plants to supply electricity from renewable sources for electrolysis.

In the electrolysis process carried out by electrolysers, water is split into hydrogen and oxygen.

The hydrogen produced is stored in containers specially designed for handling gases and delivered to fuelling stations, where it is offered for sale to the public through a dispenser.

The hydrogen is then converted on board FCEVs back into electricity for propulsion, which is brought about by the platinum-catalysed fuel cells, and the vehicle ends up emitting only water as steam.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here