The pirating of a Greek-owned tanker, the Kerala, in Angolan waters on 18 January 2014, might have been a probe to see if such an operation could yield profitable results for the sea bandits. As criminal activities go, the job was most successful. The pirates pulled off 2014’s first big international heist, departing with 12.3 metric tonnes of diesel via three ship-to-ship transfers. The Kerala went missing for a week and when she again made her presence known to the world, the vessel was floating off Nigeria’s coast. The location suggested that Nigerian pirates were responsible for the hijacking.

With international support in 2013, the Nigerian navy was able to curtail some piracy activity in the Gulf of Guinea. The sea lanes in the gulf will not resemble those in the Indian Ocean off Somalia. While Nigerians are operating the Gulf of Guinea’s piracy operation, and Somalians are responsible for piracy off their coast, Somalia does not have a functional navy capable of halting piracy activity. A prosperous nation compared to Somalia, Nigeria has naval capacity and a political will to safeguard its sea lanes (see the article ‘West Africa – security threats and cooperative solutions’ in the March 2014 edition of ACMM). Securing the safety of oil shipments is paramount to Nigeria’s vital oil production industry, as well as for a wealth of other exports and imports.(2) 30% of the United States (US) oil imports pass through the Gulf of Guinea, and American military assistance has helped Nigeria confront the maritime menace posed by piracy. While more than 40 piracy attacks were recorded in the Gulf of Guinea in 2013,(3) with a considerable naval armada armed against them, pirates’ interest in moving further southward suggests a desire to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Two factors suggest that Nigerian pirates hijacked the Kerala. The ship was taken in territorial waters and not the high seas. This is the Nigerian pirates’ modus operandi in the Gulf of Guinea, and was followed within sight of the Angolan shore. Secondly, Nigerian pirates prefer oil tankers, and indeed the Kerela’s cargo, which was diesel fuel, was removed from the vessel in an efficient manner that showed practice and know-how. The tanker was taken northward to be unloaded in Nigeria, where the incidents of piracy increased in exact correlation to the diminishing number of acts of vandalism against oil pipelines on land. A drastic drop in such acts from near 4,000 in 2000 to about 500 in 2002(5) corresponded to a sudden rise in the Gulf of Guinea’s piracy incidents.(4) The Nigerian criminal syndicates found it more profitable to steal oil by sea, rather than land. On the positive side, the number of civilian deaths from incineration has dropped, as fewer poor residents near vandalised pipelines seek to capture leaking crude from the ruptures and are caught in conflagrations when sparks or lit cigarettes cause the oil to ignite.

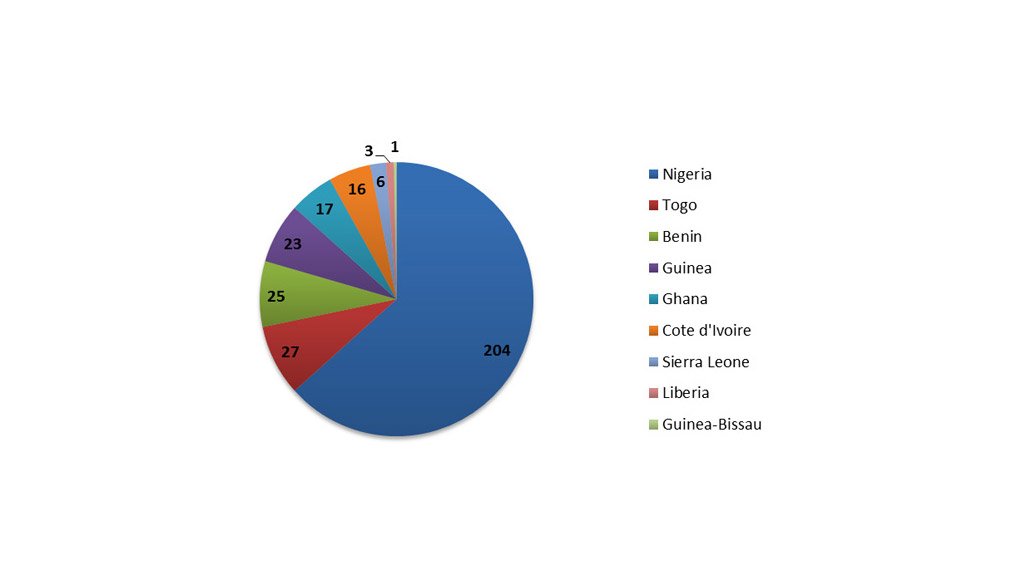

Fig 1: Location of piracy incidents in West Africa, all incidents recorded 2006-2012 (6)

Angolan, Namibian and South African navies, individually and conjoined in anti-piracy operations, are capable of policing their coastal waters (see the article ‘Intelligence-sharing and law enforcement in Southern Africa’ in the March 2014 edition of ACMM). However, a more intractable problem will remain. The hijacking of the Kerala off Angola’s coast not only raises the immediate concern of Somalia and Gulf of Guinea-style pirates terrorising South Africa’s sea lanes, but highlighted long-standing security concerns inherent with foreign-registered ships. So serious are criminal and environmentally-damaging acts associated with ships sailing under ‘flags of convenience’, that Angolan naval authorities used such ships’ reputations as a subtext in their denial that the Kerala hijacking took place. The Kerala was listed under the Liberian International Ship and Corporate Registry (LISCR). The LISCR is the world’s second largest ‘open registry,’ which is a corporation in partnership with a host government that registers vessels owned by foreign nationals. The Kerala’s registration with LISCR alone is insufficient for Angola to declare that the vessel was a willing participant in its own hijacking. That assertion was based on observations made at the time that have been subsequently discredited. Most LISCR ships are registered by owners seeking economic advantage, and not as a way to further criminal and terrorist agendas. However, such agendas have been served by craft flying flags of convenience.

The Kerala’s foreign registration raised suspicion

Angolan authorities were taken by surprise when informed that the Kerala was hijacked near Luanda’s port. The facts, as gathered by Interpol and confirmed by LISCR, are that pirates of unknown identity and origin (though for the aforementioned reasons most likely Nigerian) boarded the 75,000 tonne Kerala, which was fully-laden with 60,000 metric tonnes of diesel. The pirates disabled the AIS (a nautical GPS system) and painted over the tanker’s name and identifying numbers. Unable to track the ship by land or satellite, the ship’s owners, Dynacom Tankers Management, only heard from the Kerala’s crew of 27 Indian and Filipino seamen on 26 January, once the pirates had left and the tanker’s communications were restored. The tanker dropped anchor at the nearest port, which was Tema in Ghana. A return to Luanda seemed unwise given the Angolan authorities’ insistence that the ship hijacked itself.

A spokesman for Angola’s navy, which was responsible for the Kerala’s safety within Angolan waters, denied the incident ever happened. One crewman was wounded by pirates, but the Angolan military spokesman said the hijacking was “faked” (7) by the crew, perhaps for the insurance money or to make a profit from the stolen diesel. Dynacom called the charge “ridiculous, unfounded and laughable.”(8) With a domestic oil industry and valuable oil exports that could be affected by adverse publicity, and embarrassed that the first piracy incident south of the Gulf of Guinea should occur on its watch, Angola went into denial mode.

Assisting Angola was the fact that ships sailing under a ‘flag of convenience’ have a poor reputation in terms of criminal involvement, environmental damage and even the opportunities they offer terrorists. As suggested by a 2003 report by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), if the Kerala had been laden with liquefied natural gas and hijackers had sailed the tanker into Cape Town harbour and detonated the cargo, all that would remain of the city’s waterfront would be pleasant tourist memories.

For the existence of ‘flags of convenience’ (a term coined in the 1950s) we can credit regulations-hating American business people. The phenomenon of US businesses fleeing their home turf to avoid safety and environmental controls, as well as having to pay employees living wages is not new. So upset were US ship owners over a 1915 law, the Seaman’s Act, which mandated lifeboats and decent food on merchant ships and prohibited 20 hour workdays, that they began registering their vessels in Panama, where seamen’s wages were pegged to the much lower pay of Imperial Japan. Thus was born that part of globalisation that dealt not just with expanding markets, but literally ‘shipped out’ jobs overseas where wages were small and workers’ benefits and workplace safety standards were often non-existent.

Just as criminals and tax evaders hide their money in overseas accounts to avoid detection, foreign-flagged ships have been used to hide unscrupulous activities. As a harbinger of mischief to come, the very first foreign ship to register in Panama in the 1920s, the Belen Quezada, was used to illegally transport alcohol between Canada and the US, where alcoholic beverages were banned from 1920 through 1933 under the Volstead Act.

Although Panama in 2014 maintains the world’s largest open registry for ships, Liberia comes in second. The two countries and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific account for 40% of the world’s commercial shipping fleet as measured by deadweight tonnage, or the weight of cargo a ship can carry. Liberia’s LISCR, as it is known today, is a joint venture with the Liberian government created by former US Secretary of State Edward Stettinious in the 1950s after US shippers complained of political instability and higher registry fees in Panama. The Liberian government’s share of the registry’s profits accounted for up to 70% of government revenue in the 1990s. Registry income financed one of Africa’s most brutal regimes by providing the principal source of legal income for Charles Taylor’s government.

In addition to Liberia, Equatorial Guinea maintains an open registry for foreign-owned ships. Other African countries that make money this way are Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe.(9)

Dangers of crime and terrorism associated with unknowable ship owners

How government revenues from ship registrations are used or misused has been a lesser issue than the malpractices of ship owners sailing under flags of convenience.(10) Using an open registry, any ship’s true owners can be disguised. This raises concerns that third forces such as terrorist groups, insurgencies and arms dealers can possess their own fleets. The UN Secretary General’s Consultative Group on Flag State Implementation noted in 2004 that “it is very easy and comparatively inexpensive to establish a complex web of corporate entities to provide very effective cover to the identities of beneficial owners who do not want to be known.”(11) The group was created to investigate actual and potential abuse associated with ships operating under flags of convenience.

Honduras shut down its open registry in 1982 because numerous ships flying the Honduran flag were found transporting illegal narcotics. In 2000, international media stories were generated when ships flying the Cambodian flag were implicated in the smuggling of drugs into Europe, breaking international oil embargoes and involvement in human trafficking. The Cambodian government cancelled its contract with the firm operating that nation’s open registry, the Cambodia Shipping Corporation (CSC), after the French navy seized a CSC-registered ship in West African waters in June 2002. The freighter’s cargo was a shipment of cocaine worth US$ 230 million.(12)

The OECD’s 2004 study found that because ship owners can remain anonymous by registering their vessels using an open registry, opportunities for criminal activity that go beyond tax evasion are numerous.(13) The OECD report noted that such ships can be used to transport weapons or even become weapons themselves if they are rigged to be floating bombs or transport containers bearing nuclear or chemical weapons.(14)

Because ship owners may disguise their identities by operating their vessels under flags of convenience, they are able to evade prosecution. Thus ‘indemnified’, ships operating under open registries are at the forefront of illegal fishing worldwide. Wanton industrialised fishing carried out by such ships is threatening coastal African nations’ fishing resources. The potential for environmental and economic damage does not end there. Some of the largest oil spills involving tanker ships have been caused by foreign-flagged ships that may sail with under-paid crews working in deplorable conditions and with minimal safety standards.

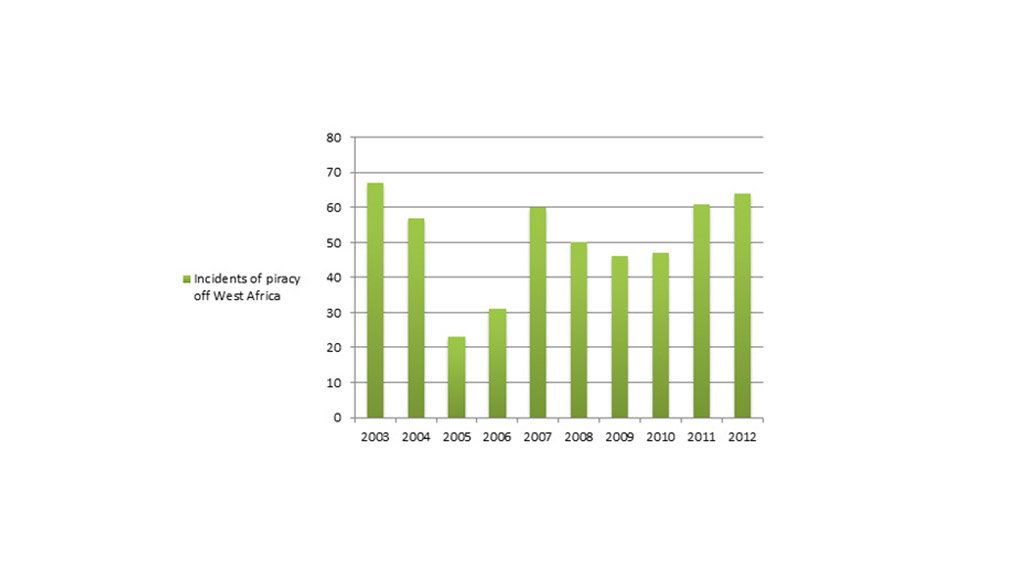

Fig 2: On the rise: Incidents of piracy off West Africa 2003-2013 (15)

Angola may be disingenuous with its hijacking denial, but has a point about foreign-registered ships

While Angola might exploit the dubious reputation of foreign-registered ships to create a diversion away from a piracy crime committed outside its capital city, that tactic will work only once. Angolan and South African naval authorities must determine whether the Kerala hijacking was a once-off probe to test the vulnerability of Africa’s southern Atlantic waters, or whether the crime signals a new danger to international sea lanes of which Angola, Namibia and South Africa are custodians off their coasts. Somalia pirates have localised their activities off the waters of their home country and have not ventured south to Kenya, Tanzania or Mozambique. Nigerian pirates, the most likely candidates behind the Kerela pirating, displayed a different will and technical capacity when they executed a successful hijacking off Angola’s coast.

Meanwhile, further international scrutiny will be given to foreign-registered ship standards. Most foreign-registered ship owners are more interested in dodging taxes than running narcotics, and would welcome having their sullied reputations burnished, even at the price of tighter regulations.

This article is extracted from the March 2014 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM) – the brainchild of award-winning journalist and columnist, James Hall. The +-70 page report dissects conflict trends across the African continent to guide businesses, governments, academics and other stakeholders in Africa’s growth and stability. Click here to find out more about ACMM.

Written by James Hall (1)

Notes:

(1) James Hall, Founding Editor of the Africa Monthly Monitors (AMMs) and critically acclaimed author, columnist and filmmaker, pioneered insider coverage and analysis of Africa, in Africa, with six books and thousands of articles and news stories for publications worldwide. Contact James at jhall@realnet.co.sz. Edited by Dominique Gilbert.

(2) ‘Piracy report says Nigerian waters the most deadly’, IRIN, 4 April 2004.

(3) Starr, B. and Shoichet, C., ‘Two seized in pirate attack off Nigeria, US officials say’, CNN, 25 October 2013.

(4) ‘2011 Annual Statistical Bulletin’, Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, 2011.

(5) ‘UN says incidents of piracy off Africa’s West Coast increasing, becoming more violent’, AP, 27 December 2012.

(6) 'Transnational organised crime in West Africa: A threat assessment, February 2013', United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

(7) ‘Greek tanker operators owners insist vessel hijacked off Angola’, AFP, 27 January 2014.

(8) Ibid.

(9) ‘What are flags of convenience?’ International Transport Workers’ Federation, 2013.

(10) Shaughnessey, T. and Tobin, E., 2004. ‘Flags of inconvenience, Freedom and insecurity on the high seas’, University of Pennsylvania, pp. 2-3.

(11) Gianni, M., ‘Real and present danger: Flag state failure and maritime security and safety,’ International Transport Worker's Federation, 2008.

(12) Bainbridge, B., ‘Drug ship sparks probe’, The Phnom Penh Post, 21 June 2002.

(13) ‘Ownership and control of ships,’ Maritime Transport Committee, Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003..

(14) Ibid.

(15) Graphic by ACMM with data from ‘Reports of piracy and armed robbery against ships 2003-2012’, International Maritime Organisation.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here