We are living in a time where rogues seem to abound. Some are giant ones, some are lesser or even apprentice rogues. Others are rogues-in-the-making, who are learning the craft from the master thieves and fraudsters who populate the leadership of the ANC, and some organs of state. It is a time of widespread abuse, absence of concern for the wellbeing of others and willingness to cause harm or injury to others. Together they signify rejection of what many saw as foundation stones of the “new South Africa” that was supposedly inaugurated in 1994.

Stealing from the fiscus, which is supposed to be drawn on to address the needs of all and especially the poor, is now a common practice at all levels of government and apparently is becoming worse not better.

But there may still be a wellspring of good will, battered but still present in the ethos of many people who are struggling to find a way forward that is not tarnished by bribery and malfeasance of various kinds. This is a time when people are desperate to discover heroes or heroines. In this time of widespread dishonesty and dishonourable conduct, many long to find exceptions, leaders who have integrity and who are concerned about the wellbeing of all and not just about their own enrichment or advancement. That is why, understandably, individuals who experience victimisation or refuse to allow irregularity are often seen to have more generalised qualities, which leads to unrealistic expectations.

There is a desperate, often unspoken or inarticulate desire for a leadership that can be trusted, that can initiate a new beginning, reignite the ardour with which many sought to contribute to a society freed from the yoke of apartheid and promising ever-widening and deepening freedom. I agree with the need for ethical leadership, but what is it that we are looking for that can endure beyond the immediate task of ending the misfortunes visited on us under Jacob Zuma?

Beyond the removal of Zuma and his shrinking coterie, what is the plan, what is the vision that is offered? What is it that we want for South Africa now? What is the plan beyond Zuma falling?

The Freedom Charter declares that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white. At a certain point there was a sense of belonging that people felt or claimed in the new South Africa, including a desire on the part of many whites to assert their being African. Unlike the time when they were called “Europeans”, they now wanted to assert their link with the country, the continent and the people as a whole. Many felt hurt and excluded by definitions of the word African that did not include them. (See my discussion of such terminology in Recovering Democracy in South Africa, 2015, Jacana Media, pp. 129-131).

That sense of belonging also related to a particular type of leadership that sought to join itself to the communities it represented and to expand that connection beyond the core constituency that the ANC then represented - the poorest of the poor – in order to embrace South Africans in general. This was exemplified in the personal conduct of the great leaders of the time.

The much-revered leaders of the past were pained by what they, their families and other oppressed people had experienced under apartheid. Their life work, as members of freedom organisations, was a dedication to remove the daily humiliations and the conditions of oppression manifested in every facet of the lives of black people. In so doing, they would bring freedom to all South Africans.

What are the qualities that a leadership and new movement need to embrace, be imbued with, in order to win trust and use that trust and mandate to chart an emancipatory path forward?

1. There must be integrity. Leaders at all levels must be trusted and that trust is won in the first place because they act with honesty. They do not lie. They do not promise what they have no intention of doing. They do not steal. They do not use unfair or illegal methods in order to benefit themselves or others close to them.

2. Leaders must act to stop the violence that runs through South African society, not only emanating from the security forces and certain officials, but increasingly in protest movements, as we now see. Violence is normalised in the lives of the poor, who remain primarily black. Someone remarked on social media that there are only headlines when there is burning in Braamfontein, yet this is a daily experience in more impoverished areas. Likewise, acts of violence operate not only in what is captured in the media, but in every nook and cranny of South African society, often at the instance of officials who are charged with upholding the law. Violence runs through South African society, making streets and lanes, buses and trains, taxis and offices unsafe places for men and women, but especially women.

Women and members of the LGBTIQA communities are subjected to far more aggression than is reflected in the media or police statistics because of the barriers to reporting, which remain hurdles and lead to grossly inadequate policing and prosecution of these crimes.

There is a more long-term and fundamental danger attached to the widespread use of violence in South African society, where violence is seen not only by the state, but also by many in student protests, as a way of achieving political goals. The danger, alluded to by Richard Pithouse, is that we may see the current crises unfolding into an “authoritarian resolution”. (See Writing the Decline (Jacana Media, 2016, p. 4). How that unfolds is difficult to predict, beyond noting that the current leadership has been willing to deploy force to address social conflicts. It is not unthinkable that they may do so more comprehensively. Insofar as the ANC now faces the real prospect of losing power in 2019, it may well be that there is a temptation in some quarters to use such an option.

But it is important to understand that even if that is a preferred option on the side of the powers that be, citizens are not without resources to resist and it is important in considering what lies ahead to build an organised force that is sufficiently powerful and united to deter any attempt to seek a bloody anti-democratic option.

3. Leaders need to cultivate bonds of connectivity and solidarity. Leaders need to build less impersonal relations with their constituencies, establish or re-establish bonds of responsibility and solidarity - what some feminists call an “ethic of care” or connectedness.

It may well be that the new local governments elected in August will operate more efficiently than the ANC administrations they displaced, but they have not expressed the desire to build the type of relationship of solidarity that the ANC used to have with its constituency. The ANC ruptured or revoked that connection with the poorest of the poor by acting in ways that undermined their wellbeing. That connection must be re-established between the democratic forces to be built and consolidated and the oppressed communities.

4. Leaders need vision. It may well be that some people have courage and have now or always “stood up to be counted” and been unafraid of the consequences in terms of their personal wealth or the positions they hold. But we require more from leaders. We need a sense of vision. We need people who indicate how things should unfold in order to reinvigorate and enhance our democratic polity and how those currently excluded will benefit in the future.

But from where does this vision derive? We are not speaking of being learned or being able to understand a problem, though it is essential to identify and understand the dimensions of a problem in order to remedy it. A vision that engenders trust is one that derives both from the insights that a leader may display and also the insights that come from listening to people, hearing how they experience their own hardships. In advancing a vision that wins trust, it is important that people should see their own experiences embodied in the vision so that when some or other injustice is removed or “falls”, they will recognise it as resulting not only from the wisdom of the leaders, but also their own contribution towards what unfolds.

None of these are unimaginable qualities. As indicated, they were found amongst some of those who were leaders in the struggle, including some who have come to turn their backs on what they did in the past.

There are no quick fixes in politics, especially in so complex a society as ours. Building the type of organisation that will take responsibility for the future on an emancipatory basis will require patient, mature and non-sectarian building of unity.

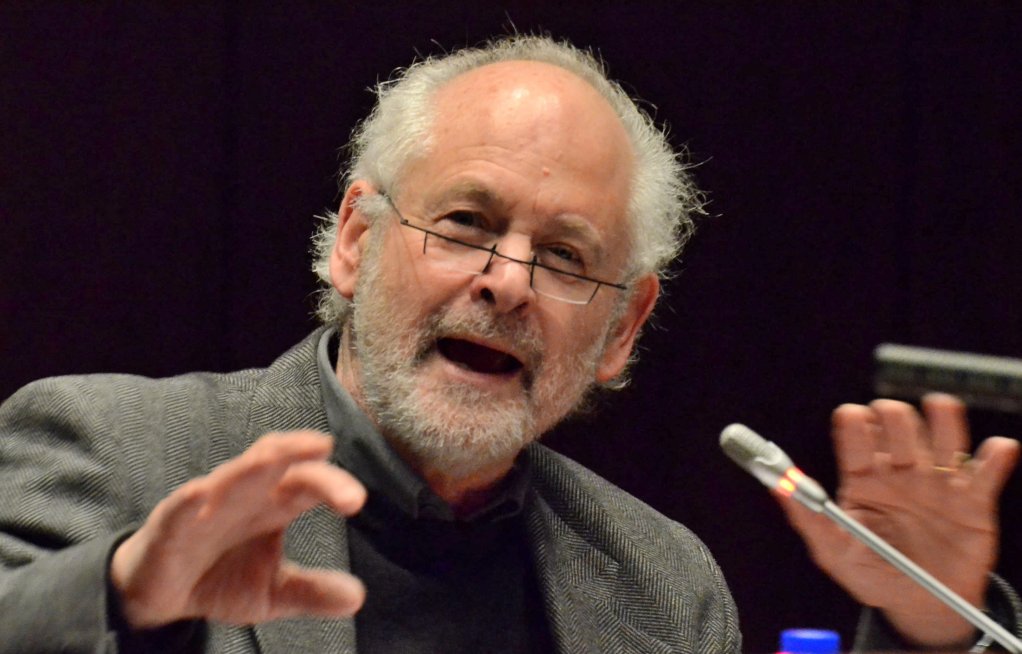

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. He is a former political prisoner for activities in the ANC-led liberation struggle. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes University and an Emeritus Professor at UNISA. His most recent book is Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana and Lynne Rienner, 2015). He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here