This is an adapted presentation made to the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) Annual General Meeting, Constitutional Hill, 3 October 2019

I value the work of the LRC over so many decades, resulting in some of the most path-breaking court decisions.

I am a qualified advocate but have had very little practical experience. I have more experience in working as an academic lawyer by day and as a lawbreaker under apartheid by night from the late 1960s. And that points to a central question that we need to have people recognise in all its implications. It relates to what changed and what did not change after 1994, in this case, concerning law.

Some people do not acknowledge that things have changed significantly since the demise of apartheid and since the onset of democratic governance. Some suggest that nothing significant happened in the transition or that there was a betrayal of freedom and the poor. My argument is not to deny that the inequalities of the apartheid era have continued and even worsened in the post-apartheid era. Nor do I deny that there are many cases of abuse, some of which we are now learning.

In general, I think it is essential to appreciate that all situations of radical change, which I think we underwent, always have ruptures coexisting with continuities.

Law-then and now

But when we address what changed and did not change with frameworks of governance and the law, there is a very clear general picture.

My readiness to break the law 50 years ago was because it was a rights-bearing law for whites and a rights-denying law for all black people, albeit with some differences in the condition of Africans, Coloureds and Indians. I believed, as a person who was committed to universal human rights, that I owed no allegiance to this illegitimate legal system and constitutional order.

Repression, law and ideology under apartheid and now

Apartheid law entailed massive repression against black people. But it cannot be understood only as repression, and that has relevance to the present. Apartheid law was both simple and complex, simple in that whites experienced law as privilege, but it signified oppression for black people.

But part of its complexity lay in that law also operated with attempts to legitimate itself to the oppressed. Although the apartheid regime survived, in the final analysis, through repression, it understood the need to try to secure a measure of consent.

And the judiciary played some role in these ideological efforts to secure consent. Judges would often invoke "society" and how society supposedly understood an offence and what type of sentence society was to have wanted, in deciding on heavy sentences, often imposed on political offenders. In one Group Areas case, the Court held, against the argument of counsel that the public viewed breaches of the Group Areas Act as criminal. In the sentencing of Barbara Hogan for treason, Judge van Dyk stressed "society's" demand or expectation that a heavy sentence is imposed. (For further discussion see Raymond Suttner “The Judiciary –its ideological role in South Africa” (1986) International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 47-66

Equality before the law and actual inequality between parties

Legislation buttressed these sentiments, but many people believed that the common law, drawn from Roman-Dutch and to some extent English law, was a repository for equal values and human dignity. There was an element of truth in this, but it did not always have an unambiguously positive effect. In implementing values like equality before the law, courts operated on the basis of a common law that was not racist per se. In acting in some cases where colour was supposedly irrelevant, the courts implemented an interpretation that had the effect of failing to acknowledge the difference of status and opportunity, resulting from class, race and gender.

At this level, equality before the law had the effect of erasing the difference between parties, their ability to litigate and sustain litigation or defend themselves in criminal cases, through the socio-economic conditions from which each party derived. In that way, where no one could point to prejudice, the partial mythology around the law and its equality- was itself a legitimation of inequalities. In De Beers v Minister of Mines, in 1956, the Court remarked through Judge Kuper:

"Counsel said that justice to all parties required that Sir Ernest should be called. On two occasions he told the Court that the fact that Sir Ernest Oppenheimer is a very wealthy man should not influence the Court against calling him as a witness. First of all, there is no evidence that Sir Ernest is a wealthy man: even if he is I think that the suggestion that this might influence the Court, should not have been made….It hardly requires to be said that the financial standing or status of any particular person is completely and entirely irrelevant when it comes to the question of the rights of any citizen in this country." (My italics).

This is an interesting quotation-from a relatively liberal judge, that may have some bearing today. The notion that Sir Ernest was not a wealthy man, insofar that there was no evidence -presumably in court-to bear this out is an important warning to the effect that judicial officers need to be conscious of a chasm growing between that of which they have evidence or can take judicial notice, and that which is in the consciousness of most members of South African society.

In the Zuma rape trial, some 12-13 years back, Judge Willem van der Merwe prided himself in not reading newspapers and consequently claiming to know as little as possible about the case he was deciding. "It was difficult not to see and hear some of the comments in spite of the fact that I try not to read, look or listen to news concerning a matter I am busy with in Court. Some matters unfortunately did not escape my attention…." (http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAGPHC/2006/45.pdf ) Is this a good thing, to claim to bear this ignorance, if true? Is it not essential in South Africa today that judges have substantial knowledge of the conditions of existence and other factors relating to the parties before them? Judicial training is supposed to enable one to learn about X or Y that one may or may not approve of, yet not have that deter one from taking a decision with integrity. How that is done is up to the profession, including the judiciary to work out and the present constitution may encourage or demand such awareness of the conditions of all, especially insofar as the constitution demands the advancing of socio-economic and developmental rights.

Returning to Sir Ernest Oppenheimer the Court takes umbrage against the suggestion that Sir Ernest's "alleged wealth" could influence it. Obviously, in the current period we cannot be sanguine about bias nor in the future.

But my suggestion is much more limited, that we do away and maybe we have already- with the idea that judges inhabit a world divorced from knowledge of a range of things that are commonplace to many of us. Independence is not ignorance or otherworldliness of the type which Judge van der Merwe prided himself in bringing to bear in the Zuma rape trial. The judiciary must be conversant with what is happening in the country as with the case of corporal punishment of children at home, where the courts related their decision to the prohibition of violence in general, which relates to the general history and presence of violence in South African society today.

The final sentence relates to the impact of Sir Ernest’s wealth on the Court's approach to Sir Ernest, "It hardly requires to be said that the financial standing or status of any particular person is completely and entirely irrelevant when it comes to the question of the rights of any citizen in this country."

It may well have been that the Court would as easily have found against wealthy people as for them. But the financial standing or status is not at all irrelevant -not then and not now. It affects the capacity of parties to continue litigation, even if they are in the right. One has access to legal aid in limited cases and up to an income threshold and other specifications and exclusions. But one can find oneself pitted against an institution that can litigate indefinitely should it so decide.

This is where the LRC and other public interest law centres come in, though not duplicating legal aid provided by the state but to ensure that cases that have a public interest are not barred because of lack of funds. But their reach is limited, and many essential cases will not get to Court, in 2019 or the next few years due to lack of funding.

How law and ideology work

Under apartheid, the courts played an ideological role in its pronouncements, notably in the imposition of sentences, for example, where judges often invoked "society", as if it was a homogeneous phenomenon, and it was the Court who took it upon itself to speak on behalf to this supposedly totally cohesive society. In this context "society" sometimes demanded a heavy sentence or something similar. In other words, the sentencing process became a legitimation of the law of the time and a delegitimation of the accused/convicted political accused and their actions taken in support of freedom.

It became a process which erased the reasons for the actions of the political accused and the cause of freedom that s/he claimed to be representing in the activities for which she was convicted. The person was found guilty or innocent as a result of the evidence that was relevant to the charge, that s/he did or did not do this or that. The reason why the accused did this or that was generally not legally relevant to the facts in issue and could at best form part of the mitigation of sentences. Many judges took it upon themselves to impugn the motives of the accused or even slander them. To some extent, this happened in the Rivonia trial sentencing statement of the judge, where he suggested that the hope for personal political gain may have motivated the accused.

A court case-then and now- is intended to be an authoritative account of what happened or what issues were at stake in one or other matter. The way the law operates is to delineate a narrow range of matters as being justiciable and thereby deny the relevance and admissibility in Court of certain others. There is a narrative of what happened that is often contested between the state and the accused. The Court's judgement provides an authoritative account of what happened. This is still relevant today insofar as courts have to enunciate values when they decide cases and how that is done provides meanings to the public.

This did not only happen in political cases but notably with regard to customary law, used in its Native/Bantu/Black law guise, where Africans were constituted as tribal subjects, without entitlement to the rights of South African citizenship. Even for those who may have had some attachment to customary law, what emerged in the colonial and apartheid version of this law denuded it of flexibility and capacity to grow, something that is being addressed in contemporary litigation where the notion of “living customary law” is stressed.

Post-apartheid law

Now, much of this, not all, has changed fundamentally in the post-apartheid period and I do not think people give as much credit as they should to the quality of law, that now exists. In some ways, the word revolutionary -connoting fundamental change- is appropriate to compare what existed then and what is the law and constitution of South Africa today -at least on paper. It is still work in progress, as is the case with all revolutionary changes, entailing continual advances and setbacks.

It is a rights-bearing law for all, negating the differentiated subjectivity of black and white, although some of the legislation and practices relating to rural areas hark back to apartheid subjectivity, the tribal powers purportedly belonging to Traditional Leaders on behalf of their "subjects". The claim of these Traditional Leaders to that title is sometimes suspect, going back to the period when colonial and apartheid rulers displaced legitimate heirs, where they would not collaborate.

But generally, the law sought to provide all people with rights. In other words, laws for those falling under Traditional Leaders cannot deny them what remains their rights under the law of the constitution. This may well see some of the regulations and laws in relation to Traditional Leaders struck down, as has already happened. Also, all means not only citizens but with some exceptions includes refugees and asylum seekers resident in the country. There is a very limited range of rights in the constitution that are accorded only to citizens.

It will be essential to see how the courts relate to cases that may well be in the offing, whether as we should hope, they will continue to provide protection to this most vulnerable section of our society.

Current ideological role of courts

Returning to the ideological role that I have ascribed to courts under apartheid, is there an ideological role today? The courts and lawyers operate under a constitution and legal system that is based on democratic values. Every time a court decides in line with those values, it enunciates an interpretation of the type of country we are. Just as apartheid stressed impunity for officials, the Constitutional Court and all other courts need to and generally do stress accountability. It ought to come down hard against patronage and corrupt relationships, which have the potential to undermine democracy and integrity. Just as apartheid legitimated insults to the dignity of black people, the legal profession generally and courts in particular now need to advance a law that demands respect for dignity as a cornerstone value of the law and the country, as they already do.

Even though the courts have enunciated meanings of values that have been substantial there remains a lot more to be covered in all the implications of gender-based violence, sexualities, freedom of speech, treatment of refugees and asylum seekers and questions of violence.

The task of the legal profession and courts is difficult

How that constitutional entitlement to rights is put into practice is subject to a range of factors that can render its effectivity more limited. At an obvious level, we know that reporting a crime is relatively easy and effective in the wealthier suburbs. There are more police stations, in close proximity, and they usually have working vehicles and other equipment, and they are responsive to the complainants. (this is again the "Sir Ernest phenomenon" at work)

In rural areas, townships and informal settlements, the commission of an offence is hard to report and having reported offences -and this also happens with sexual offences in wealthy areas, there is often no report back, and dockets are lost and a range of unprofessional and dishonest practices intervene to render the rights inhabitants have of little value.

How often do we read that a woman who was murdered had been granted a protection order against the person who killed her, but it was not enforced, or that she had sought police protection but could not get an adequate hearing?

The promise of constitution unrealised? Laxity and intentional

Without going into it fully one of the significant problems of the current period, is that the promise of the constitution is often unrealised. This is not to say that the courts are necessarily the best place to deal with some of these issues, but they have been forced to step in as a result of paralysis or failure by other arms of government to defend constitutional rights. And that has had to be undertaken by public interest firms like the LRC

Sometimes it is incompetence or carelessness, but what we have seen very clearly in recent times is that very often the failure to realise the promise of the 1996 constitution relates to a deliberate undermining of the rights and duties conferred by law.

There has also been running down of key institutions of the state, notably in the criminal justice system. Despite valiant efforts of new leadership, it is very difficult to prepare prosecutions, given the years of decay and the continued presence in the policing and prosecuting arm of some who helped destroy capacity.

State capture. There has been a dramatic episode that may still be continuing, going beyond conventional corruption and known as "state capture" where some people sought to bypass the state procedures or to determine how these were set in motion in order to enrich themselves and their allies. To enrich oneself from public monies is not a crime without a victim, because that is taken from resources that are meant to benefit all South Africans. The victims of state capture are not some abstract “state”, but the most impoverished sections of the communities, whose resources for survival are raided by the captors.

Recovery of monies but qualified support for those engaged in a "clean up"

At this moment, there are attempts to recover monies and prosecute those responsible for these deeds and to stop others or the same people from continuing with these practices. It happens through ministerial action, through the Zondo commission and it has started to happen through the courts. It is supposed to occur through the Public Protector, but there are plausible claims that the current Public Protector is aiming her guns at those responsible for clean-ups and going soft on those who are allegedly responsible for stealing our monies.

The process of remedying state capture has unleashed a massive "fight back" against those perceived as driving the "clean-up."

The ANC was itself compromised by the illegalities and diversion of funds in the Zuma era. Some of its leading figures could well be prosecuted for their actions or complicity during that period and possibly continuing.

It may be that some of those who are in the camp of Cyril Ramaphosa are also implicated, as has been claimed in evidence to the (Deputy Chief Justice, Raymond Zondo) commission leading to the naming of a range of people, who may still face charges on the basis of benefits they received. Some have withdrawn from public office following allegations.

At a party-political level, the EFF was at the forefront of the campaign to remove Zuma and initiating the Constitutional Court decision on Nkandla. In the last 18 months, there were some at first troubling, but inexplicable statements attacked Indians in the Treasury and Minister Pravin Gordhan. (See various articles of Carol Paton on Businesslive) Later it was found that the primary reason for the attack related to the investigation of VBS bank and as evidence has unfolded it may be that the EFF is now very heavily implicated in its looting both by individuals and as a party. (See various investigations of Pauli van Wyk in Daily Maverick and amaBhungane on their site and in Daily Maverick and News 24 and investigations by the Mail and Guardian).

This has created a de facto alliance between the EFF, sections of the ANC associated with Jacob Zuma and ANC Secretary-General, Ace Magashule. But there are potentially others who are implicated who are currently associated with Ramaphosa- who could at some point join the fight back. That there is this unevenness in the Ramaphosa camp's response to state capture is seen in the minimal support given to Minister Pravin Gordhan in response to attacks on him, outside the Zondo commission and on other occasions.

What should democratic lawyers and the LRC do in these conditions?

Sir Ernest's descendants remain equal before the law to a poor family in Limpopo whose five-year-old drowned in a pit toilet. In this situation, there is a legal system, but its reach is limited, both for ordinary litigants and also for some whose cause may have substantial constitutional and human rights significance and fall within the areas of focus that LRC is developing.

For that reason, LRC remains a significant actor, along with Lawyers for Human Rights, The Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa, Section 27 and others.

But there is no reason why the legal profession should be restricting its interventions to what become court cases. This has not always been the case, especially in the 1980s, when a number of professionals made their views known inside and outside the courtroom.

We need to recognise that we live in a time when the constitution is under attack. We need to ask how we defend the law and constitution and ensure that its democratic qualities are enhanced. Can the legal profession not be part of an initiative to rebuild democracy and ensure that the defence of constitutionalism is more grounded in society at large? There is a broad democratic crisis in which we are now living, although it is not always labelled as such.

We have come to know that the democratic order and constitution represented changes that were not fully developed nor guaranteed to remain in effect. They were always vulnerable to subversion and modification. A range of key actors in whom trust was vested, abused this in order to enrich themselves at the expense of the poor. This was done through conventional corruption and abuse of powers but also in a more elaborate systemic process of state capture where the organs of state were repurposed in order to benefit some allies of former president Jacob Zuma.

The transition of 1994 was an unfinished process, though there were crucial moments like the first elections and the adoption of the constitution. But these were part of wider and ongoing processes of advance, and regrettably setbacks.

It is important to stress that we have always been in a transition that is incomplete. The question was how it would be taken further. In some cases, we anticipated the character of resistance to democratisation on the part of some reactionary whites. Many of us did not see the erosion of the democratic gains happening at the instance of leaders of the ANC, the organisation that was the prime initiator of the democratic order.

What do we do now? My belief is that the public interest law work of LRC and others is crucial in safeguarding and advancing the rights of vulnerable people who do not have the means to litigate. The funds for that work needs to be augmented, and it may be worth exploring whether LRC and other likeminded organisations can link up with some fundraising efforts where members of the public assist to ensure that the scope of the justice that is realised is widened.

But, as I have suggested, the threat facing the law today goes wider than can be addressed in court cases. In this regard, the LRC and other public interest firms need to consider forging tighter links to take the battle to defend democracy beyond the courts and into the wider public domain. This is not a battle that will be won on any single front. We need to devote ourselves to winning back and enlarging our democracy through a range of means and in several spaces. That is an urgent task of today.

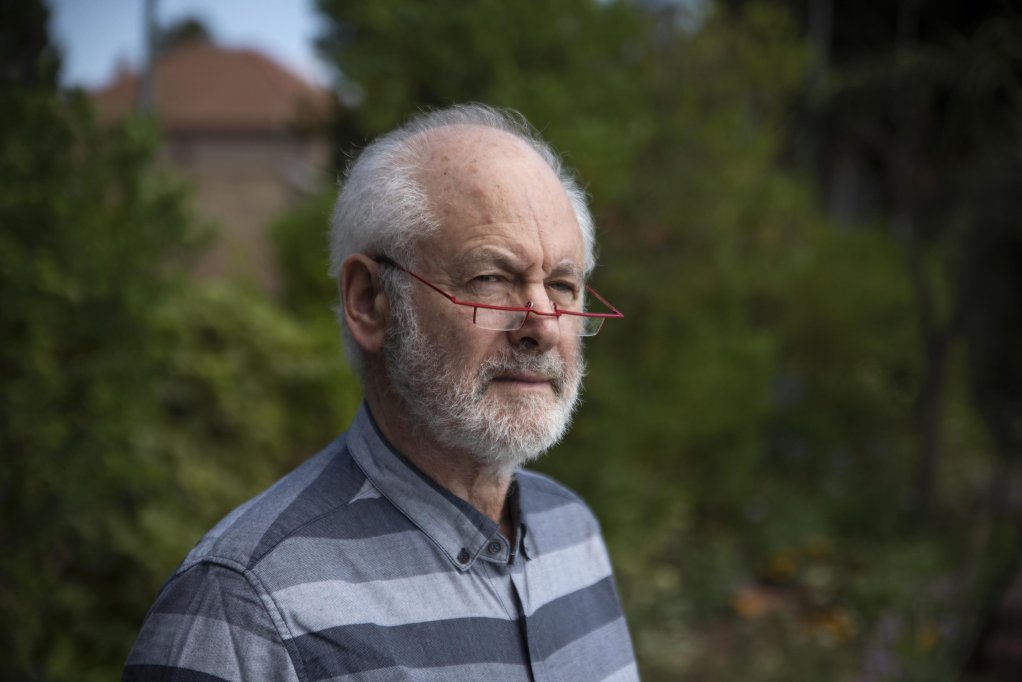

Raymond Suttner is a former legal academic and currently a visiting professor in the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg (until end of April 2020), a senior research associate at the Centre for Change and emeritus professor at UNISA. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His writings cover contemporary politics, history, and social questions, especially issues relating to identities, gender and sexualities. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here