Kenya may be on the verge of an oil boom. If oil takes off, then Kenya risks going down the same road as Nigeria, of widespread violence in oil producing areas, elite corruption and in-fighting over the proceeds of the oil industry. The characteristics which doomed Nigerian oil – high-level graft and patronage, tribal conflict and a government indifferent to the woes of oil-affected communities – are all present in Kenya. Whilst Kenya is not doomed to repeat Nigeria’s conflicts, and international extractive industry governance reforms offer a glimmer of hope for the country, Kenya has a long and difficult road ahead if it is to reap the benefits of its oil.

The well-informed Kenyan, when asked about his or her country’s oil prospects, would more likely than not reply with the popular phrase “we don’t want to become like Nigeria.” Kenya has only recently joined the ranks of nations with known oil reserves, after its first commercially viable fields were identified in the north-eastern Turkana region in July 2013 by the British firm Tullow Oil.(2) Nevertheless, speculation – and fear – abound in the East African nation over the stresses which the poor handling of large oil reserves could place on its fragile social fabric, leading to increased community conflict around oil production sites and worsened corruption and in-fighting amongst the country’s elites.

Nigerian oil has become synonymous with violence as communities in the Niger Delta fight each other for the rights to steal oil from pipelines and kidnap workers. Members of Nigeria’s political elite jostle for power and the accompanying opportunities, to siphon off oil money. Sadly, it is easy to identify the drivers of a Nigeria-style oil conflict already present in Kenya. Both Kenya and Nigeria are beset by corruption and patronage at all levels of their state structures, inter-clan conflict is rife in both countries. Additionally, early indications show Turkana communities becoming disenfranchised from their oil boom just as Niger Delta communities were with their own oil boom, decades earlier. As well as sharing conflict drivers, the Niger Delta and Kenya’s Turkana region also share conflict facilitators – small arms abound in both areas.(3)

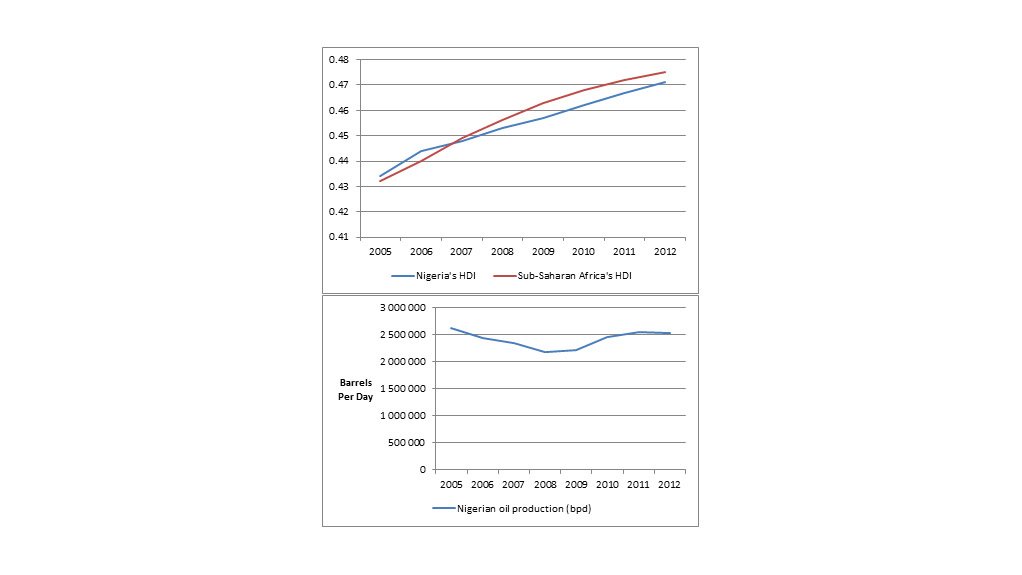

Fig. 1 Nigeria’s Human Development Index is almost identical to the sub-Saharan African average, despite Nigeria’s enormous income from oil extraction (4)

Nigeria’s proven oil reserves stood at 37.2 billion barrels in 2011,(5) whilst Kenya’s expected reserves have only just passed the 300 million barrel mark, in July 2013.(6) Significant oil reserves may not be discovered in Kenya, and the country’s oil hype may yet come to nothing. Instead of predicting an imminent conflict, it is possible to view Kenya’s parallels with Nigeria as slow-turning pistons and pulleys in the engine of conflict, which may start spinning faster the day enough oil is found to drive that engine.

Kenyan minerals

Only one oil discovery has been made so far in Kenya, by Tullow Oil in 2012 in the Turkana region. The company hopes to begin pumping oil at some point in 2014. Whilst expected reserves at Tullow’s currently-explored fields are only around 300 million barrels (see above), the company estimates that Kenya could have over 10 billion barrels of oil in total.(7) Over twenty oil companies are currently exploring for reserves both onshore and offshore throughout Kenya.(8)

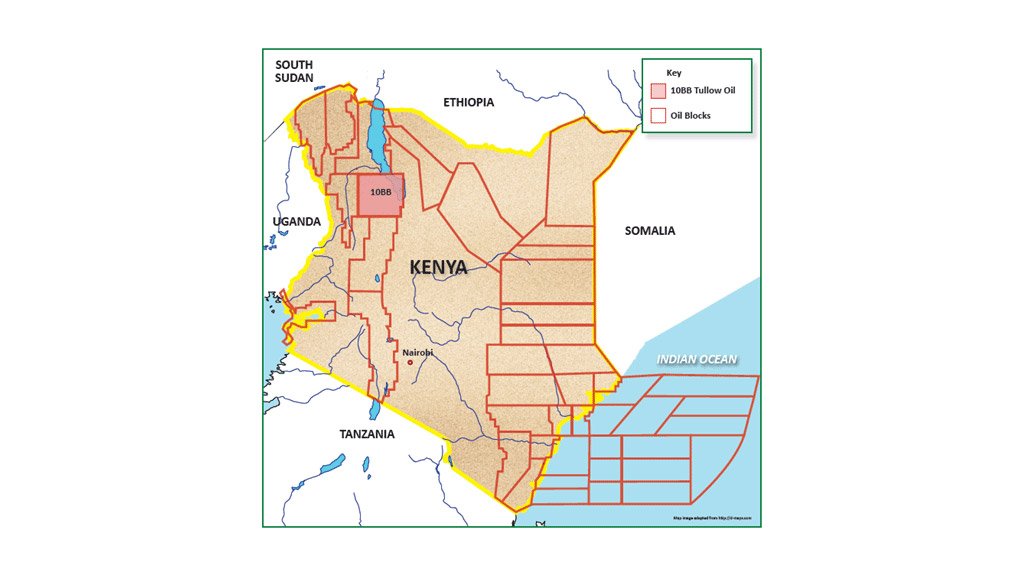

Fig. 2 Map of Kenya’s oil blocks (9)

Historically, Kenya has produced little in the way of subsoil resources. In 2010, only 0.4% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) was provided by the mining and quarrying industries. The principle minerals which Kenya does produce are cement, fluorspar and soda ash, and around 6,600 Kenyans are formally employed in the mining and quarrying industries overall.(10) Kenya’s economy is largely rural, with agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing comprising the country’s largest economic sector at 27.7% of the GDP in 2011.(11)

Nigerian and Kenyan societies are both deeply divided along tribal lines

Nigerian public life is dominated by the majority Hausa, Ibo and Yoruba tribes who, by and large, control the apparatus of the central state. Smaller tribes who wield regional power and resources – both public and private – are allocated in Nigeria along tribal lines. Citizens support leaders from their tribe in the hope that those leaders will divert a share of the country’s resources to tribe members, and leaders look to their tribes to provide them with their power bases.(12)

In the Niger Delta, this tribal rivalry translates to violent competition over scant resources in the oil economy, such as jobs with international oil firms. Near the large Escravos oil export terminal, the long-term animosity between the Ijaw and Itsekiri tribes flared due to rivalry over the awarding of jobs by the plant’s operator, ChevronTexaco. Recounting one attack on her village, an Itsekiri woman relayed that Ijaw tribes-people hacked her husband to death and burned down her house, fuelled by grievances against her tribe and their perceived closeness to ChevronTexaco.(13)

Inter-tribal attacks and killings are commonplace in Kenya. The country’s election-related violence in 2008 highlighted the profundity of tribal division in the country and its similarity to tribal division in Nigeria. Like Nigeria, Kenya is dominated by a few majority tribes, and above all by the Kikuyu, the nation’s most populous ethnic group, who control large swathes of the economy, the country’s agricultural land and the political hierarchy. As in Nigeria, inter-tribal rivalries over Kenya’s resources are frequently resolved by violent means,(14) and this rivalry could easily migrate to a Kenyan oil industry, should one develop.

Kenya’s corruption and patronage systems resemble Nigeria’s

Kenya and Nigeria’s political systems are both predicated on corruption and patronage, built around the tribal frameworks described in the previous section. The two countries are tied at 139th place in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2012, out of a total of 176 countries surveyed.(15)

In both countries, officials at the very highest levels have been accused of corruption on a grand scale. The United Nations (UN) Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that Sani Abacha, Nigeria’s military dictator from 1993 to 1998, stole approximately 2-3% of the country’s entire GDP during the years in which he was president.(16) In Kenya, the popular Standard newspaper describes graft in the country as “mega corruption,” in which inflated contracts are routinely signed between private companies and high-level government officials seeking kickbacks.(17)

Nigeria’s National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) is an integral part of the country’s patronage networks. It is one of the world’s least transparent state oil companies and has been accused by international observers of being an unaccountable monolith operating as a slush fund for the government.(18) The reputation of Kenya’s Ministry of Energy and Petroleum (MoEP) is no better. Privately, members of Kenyan civil-society organisations express grave concerns that they have almost no information on how Kenya’s oil exploration licenses have been awarded. All licenses awarded in Kenya so far have been given out through private negotiations with oil companies, and the first the Kenyan public hears about license awards is often from the successful company itself, rather than from its own government. The amounts paid by companies to the Kenyan Government for these licenses are state secrets. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was recently denied access to Kenya’s oil contracts.(19)

Kenya’s prospective oil regions are already conflict prone

The Turkana region of north-eastern Kenya is an arid pastoralist area. It is drought-prone, and conflict between communities is frequent in times of scarcity, when the various tribes who inhabit the region migrate to avoid starvation, encroaching on each other’s territories. The area is awash with small arms.(20) Conflict between the Turkana and Pokot communities – traditional enemies due to cattle rustling – was inflamed in April 2012 by Tullow’s oil find. After oil was discovered, Pokot County Council petitioned the Kenyan courts to have Turkana’s oil area declared part of Pokot territory, claiming that the land had been illegally seized by the Turkana. Turkana representatives denied the accusation.(21)

Many of Kenya’s other prospective oil areas lie on the Somali border, where instability is rife because of spill-over from the insurgency in Somalia. Humanitarian workers have been targeted in the border area for car-jackings and abductions and, were oil companies to establish a presence in the region, it is almost certain that they would be targeted in the same way – just as they are in the Niger Delta.(22)

Communities in Turkana, like those in the Niger Delta, are disenfranchised from oil

Kenya’s Government conducts almost no outreach to communities in oil-affected areas like Turkana. According to a spokesperson for Riam Riam, a Turkana consortium of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), there is widespread fear in the region that elites, both local and from the capital Nairobi, will push out ordinary local people and reap the benefits of oil for themselves. Already one of the greatest potential benefits of oil for locals – rising land prices facilitating profitable sales – is under threat. Much of the land in Turkana is communal, and there is no clear mechanism through which local land users could benefit from its disposal.(23) To make matters worse, the oil industry may be eroding the rule of law for Turkana communities. Allegedly, companies operating in the region are hiring members of the Kenyan Administration Police and the Kenya Police Reservists to provide them with security services, thereby taking staff away from community security tasks.(24) These same problems, of community disenfranchisement and of oil companies weakening the rule of law, have long been manifest in the Niger Delta.(25)

The Kenyan/Nigerian similarities are striking, but transparency is on the rise

If there is hope for peaceful and equitable exploitation of Kenyan oil, it may come from outside the country. Over the past 20 years, citizens in resource-consuming countries have become increasingly conscious of the ways in which their actions and the actions of their corporations deepen conflict and corruption in resource-producing countries. As a result, there are now international mechanisms in place which could prevent the worst excesses of oil conflict and graft arising in Kenya, and which did not exist when Nigerian oil was booming. For example, Royal Dutch Shell stands accused of paying off militias in the Niger Delta from 2005 to 2008, thereby fuelling conflict.(26) The company is incorporated in the United Kingdom (UK), and its ability to act in such a way would have been severely curtailed were the 2010 UK Bribery Act in force at the time.

To take another example, there is almost no financial transparency in Nigeria’s oil industry, and many observers contend that this is a deliberate ploy by the country’s elite to obscure the scale of corruption and fraud from which the industry suffers.(27) There are also vested interests hoping to keep Kenya’s nascent oil industry opaque, but they are now under pressure from several quarters. The landmark Section 1504 of the United States (US) Dodd-Frank Act, enacted in 2010, compels US-listed oil companies to disclose the payments they make to foreign governments. Similar legislation was enacted in the European Union (EU) in June 2013.(28) Meanwhile, local and international civil society organisations, such as Transparency International (TI) and the Kenya Civil Society Coalition on Oil and Gas, are collaborating on natural resource governance as never before. In Kenya, these organisations and others are pressuring the MoEP to disclose more information on oil contracts and to switch license awards from closed-door negotiations with individual companies to open bid rounds, in line with international best practice. The MoEP signalled its aspiration to enact such a policy in 2012, although it has yet to do so.(29)

As Kenya begins its oil journey, its parallels with Nigeria are striking and seriously disconcerting. Kenya has not yet found the sort of oil reserves whose poor handling could drastically strain its social fabric. However, if it does, the risk of conflict will be high indeed. If large quantities of oil are found, then Kenya will have to contend with state corruption, elite infighting, inter-tribal conflict and community disenfranchisement, just as Nigeria has. Today’s international oil industry is a more responsible one than that entered Nigeria when its oil boom started, and Kenya may be fated to repeat Nigeria’s experiences of oil conflict. If it is to avoid it, though, then Kenya will need to manage its oil endowment in a way which is exceptional indeed.

This article is extracted from the October 2013 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM) – the brainchild of award-winning journalist and columnist, James Hall.

The 92 page report dissects conflict trends within the African continent, with articles authored by ACMM’s team of African conflict experts. Subscribe to ACMM here.

Written by Graham Lee (1)

Notes:

(1) Graham Lee is a Key Consultant with CAI and the director of Agathon Consulting. Graham specialises in analysis of relationships between international organisations and developing-world stakeholders, and focuses in particular on risk, conflict, corruption and the extractive industries. . Contact Graham through CAI’s Conflict & Terrorism unit ( conflict.terrorism@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Dominique Gilbert.

(2) Odhiambo, A. and Omondi, G., ‘Kenya hits mark for commercial oil production’, Business Daily, 31 July 2013.

(3) Migiro, K., ‘Kenya risks oil conflict if wealth not shared: minister’, Reuters, 2 May 2013.

(4) Graphics compiled by ACMM with data from the UN Development Programme and the US Energy Information Administration.

(5) US Energy Information Administration website, www.eia.gov.

(6) Odhiambo, A. and Omondi, G., ‘Kenya hits mark for commercial oil production’, Business Daily, 31 July 2013.

(7) Gismatullin, E., ‘Kenya from nowhere plans East Africa’s first oil exports: Energy’, Bloomberg, 20 August 2013.

(8) Kenyan Ministry of Energy and Petroleum website, http://nationaloil.co.ke.

(9) Graphic compiled by ACMM with data from Kenyan National Oil.

(10) Yager, T., ‘The mineral industry of Kenya’, US Geological Survey, 2010.

(11) African Economic Outlook website, www.africaneconomicoutlook.org.

(12) Iredia, T., ‘The reality of competitive ethnicity in Nigeria’, Nigeria Today, 27 November 2011.

(13) Doran, D., ‘Nigerian tribes fight for oil jobs’, Associated Press, 24 July 2002.

(14) Pflanz, M., ‘Old scores settled in Kenya's tribal war’, The Telegraph, 1 January 2008.

(15) Transparency International website, www.transparency.org.

(16) ‘Anti-corruption climate change: It started in Nigeria’, UN Office on Drugs and Crime, 13 November 2007.

(17) ‘Corruption: Kenya’s highly infectious, malignant cancer’, The Standard, 6 September 2013.

(18) ‘Nigeria’s oil: A desperate need for reform’, The Economist, 20 October 2012.

(19) Wahome, M., ‘Kenya denies IMF access to secret mining agreements’, Business Daily, 21 July 2013.

(20) ‘Kenya: Drought exacerbates conflict in Turkana’, IRIN, 29 July 2011.

(21) Ndanyi, M., ‘Kenya: Oilfields fuel Pokot and Turkana dispute’, The Kenyan Star, 18 April 2012.

(22) ‘Kenya-Somalia: Insecurity without borders’, IRIN, 17 September 2010.

(23) ‘Kenya: Oil, hope and fear’, IRIN, 29 May 2012.

(24) Kabiru, L., ‘Why Kenya should mitigate security risks in oil, gas sector’, Business Daily, 31 July 2013.

(25) ‘Nigerian oil fuels Delta conflict’, BBC, 25 January 2006.

(26) Smith, D., ‘Shell accused of fuelling violence in Nigeria by paying rival militant gangs’, The Guardian, 3 October, 2011.

(27) ‘Nigeria’s oil: A desperate need for reform’, The Economist, 20 October 2012.

(28) Tran, M., ‘EU's new laws will oblige extractive industries to disclose payments’, The Guardian, 12 June 2013.

(29) Obulutsa, G., ‘Kenya says explorers to start bidding rounds for oil blocks’, Reuters, 25 Oct 2012.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here