Following the process of re-integration in 1993 and 1997, aimed at deepening “tripartite programmes of cooperation in economic, social and cultural fields, research and technology, defense, security, legal and judicial affairs,”(2) the Treaty for the re-establishment of the East African Community (EAC) was signed in 1999 and came into force in 2000 to promote economic development, among others. Since then, across the five partner states of the EAC (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda), an innovation culture has emerged, economies have grown, and investments and aid aimed at boosting priority infrastructure have been promoted. To some extent, this trend reflects what happened in East Asia over the last two decades.

While there are development gaps that exist between the EAC and East Asia, both continue to experience structural transformations. The difference (in the context of this paper) is that most East Asian countries have largely transformed from producing and exporting low-quality goods and services to producing and exporting high-quality goods and services, while EAC partner states are still at the embryonic stage of this transformation. Part of this transformation is related to non-conditional aid and the commitment to strengthen innovation capacity and priority infrastructure. But it is yet to be clear if this commitment in the EAC can be sustained to catch up with the level of development in East Asia and other developed countries. This paper examines whether the EAC will follow the East Asian development trajectory or its own, ultimately arguing for a Pan-African development trajectory in the EAC.

Innovation, priority infrastructure and foreign aid in the EAC and East Asia’s development

The comparison between the EAC and East Asia is instructive for two primary reasons. First, the EAC is “considered one of the world’s fastest and most progressive economic blocs,”(3) and this reflects its regional pre-eminence as a place of increasing attention to innovation and priority infrastructure. The EAC was the biggest contributor to trade in Africa in the past five years.(4) In “all eight African regional economic communities, the share of Africa in total trade was highest in the EAC.”(5) The share of EAC total trade amounted to 23.1% in the period from 2007 to 2011, compared to 16.4% for the Southern African Development Community (SADC), 14.3% for the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), 14.2% for the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), 13.3% for the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), 10.2% for the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), 9.3% for the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and 5% for the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU).(6) The reasons behind this improved trade in the EAC include increased government support and aid funding for innovation and priority infrastructure, as well as service improvements in the two major EAC ports, Dar es Salaam and Mombasa.(7)

Second, the East Asian economy is one of the most successful regional economies of the world. East Asia is thus an ideal case for elucidating a development trajectory based on building innovation capacity and priority infrastructure because of “the unusually wide range of economic development levels,”(8) and its projected potential to take over the European Union (EU) as the largest trading region and source of support for innovation and priority infrastructure to the EAC.(9) Even though the EU remains the EAC’s number one development partner (through aid funding and trade), its importance in that regard is diminishing because East Asia is increasingly becoming both an import source and export destination for the EAC.

In view of the above, this paper adopts the definition of priority infrastructure provided by the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA). According to the PIDA, current priority infrastructure in Africa refers to energy, transport, information and communication technologies (ICT), and trans-boundary water resources.(10) Similarly, it takes the definition of innovation to be the introduction and diffusion of new ideas or improved goods, services, production processes, marketing methods and ways of doing things in an economy, society or institution.(11) And foreign aid is used to mean “financial flows, technical assistance, and commodities that are 1) designed to promote economic development and welfare as their main objective (thus excluding aid for military or other non-development purposes), and 2) are provided as either grants or subsidized loans.”(12)

East Asia

Like the EAC, East Asia consists of five countries – China, Japan, Mongolia, South Korea and North Korea. With the exception of North Korea, and to some extent Mongolia, innovation, priority infrastructure and foreign aid in East Asian countries were vital in accelerating economic growth/development and raising standards of living. Japan, for example, drew on funding from the World Bank from 1953 to 1966 to lay the foundation for its economic growth through infrastructure development.(13) Chinese Taipei and South Korea benefited from the United States’ post Second World War development aid, which was used to support a huge number of priority infrastructures, like roads, ports and power generation.(14) Japan, South Korea and China (especially the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong, Macau, and the mainland municipalities of Shanghai and Beijing, as well as Zhejiang province) developed the innovation potential of their tertiary education systems. Their governments supported the upgrading of research centres and universities to offer specialised courses. With this, governments, tertiary institutions and industries were linked together to transfer technological innovations that satisfy development needs.

In terms of the role of foreign aid in the development, East Asia is in many cases recognised as the most successful aid model. A key characteristic of this is the type of aid that was given to East Asian countries, as well as the source and purpose of aid. For example, Western and Japanese aid to South Korea and Chinese Taipei (and other Special Administrative Regions) was mainly directed toward economic infrastructure, education and human resource development.(15) These areas, combined with foreign direct investment, political stability, social integration, access to Western markets, role of the state and cultural mindset have been fundamental in East Asia’s development.

EAC

Soon after gaining independence in the 1960s, EAC member states showed promising economic performance. However, this trend was partly reduced by the aid and policy conditions of the Bretton Woods Institutions and Western governments to low income countries. For example, as its original name - The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD/World Bank) -implies, the World Bank’s original mission was the reconstruction of Europe. Once this was finished, the Bank would move its attention to low income countries.(16) Alas, while aid to East Asia was intended for the development of economic infrastructure and capacity development, aid to the EAC and other low income countries was mainly to remedy the short-term balance of payments problems, and provide interim support for longer-term balance of payment problems. This was because the Bretton Woods Institutions and Western governments departed from the “approach taken in the 1950s that emphasised infrastructure development, for instance, roads and railways, telecommunications, ports, and power facilities”(17) and, unlike in East Asia, aid to the EAC and other low income countries was dominated by a series of conditions.

Nevertheless, the rise of East Asian countries as non-traditional aid donors in the EAC has created competition in the international/foreign aid regime. Stiglitz in his brief analysis of East Asia’s Lessons for Africa posits that because “developed countries have repeatedly broken their promises of aid or trade,” Japan (and other East Asian countries) have come to the aid of Africa in general to meet what he terms “a genuine moral imperative, namely that those who are better off should help those in need.”(18) This is being witnessed in some of the East Asian development fora – the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, and the Tokyo International Cooperation on African Development. The growing importance of East Asia as a development partner for Africa implies that the structural transformation in East Asia has weakened what Fourie calls “the binary distinctions of the post-Cold War era that largely divided the world into developed and undeveloped countries.”(19)

Today the EAC presents a progressive picture with notable successes. From 2007 to 2011, three of the world’s fastest growing countries were in the EAC (Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda), and their growth has largely, but indirectly, been attributed to innovation, priority infrastructure and Asia’s investment aid, which is focused on promoting trade, among others.

Aside from the above, when all five partner states of the EAC presented their 2013/14 financial budgets, the prime targets were to sustain a high economic growth. Therefore, they increased their budgets for scientific, industrial, agricultural and technological innovations, as well as priority infrastructure to meet this target. This is in line with the fourth EAC Development Strategy (2011-2016) that outlines a particular focus on the development of innovations and priority infrastructure as some of the key factors in the development and competitiveness of the regional economies.(20) Additionally, this development strategy takes into account the national visions and strategic development plans of the EAC member states and brings them into harmony - heading “together towards regional convergence into a middle income economy by the year 2020.”(21) So far, construction work on the EAC priority infrastructure projects that have already commenced or been launched include the Arusha-Namanga-Athi River road (an important section of the East African Road Network providing linkages through Tanzania and Kenya to Uganda and on to Rwanda and Burundi), the power interconnection project between Kenya and Tanzania at the Namanga border post, and the East African Railways.

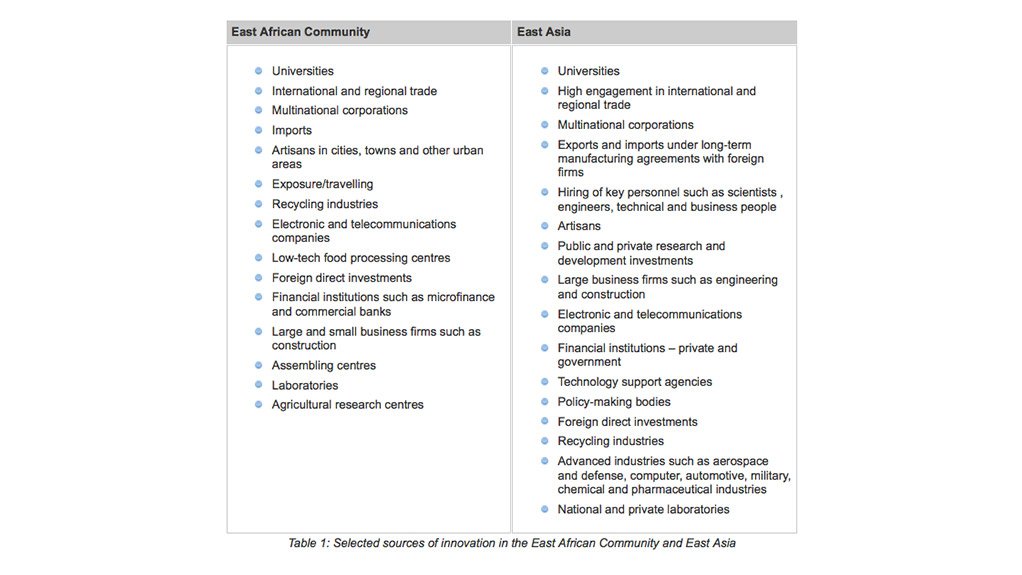

In terms of innovation, the community is strengthening cooperation with China, South Korea and Japan to support industrial, agricultural and technological innovation. Similarly, some member states (Uganda, Rwanda and Kenya) have established presidential initiatives to support innovation and science. They have also started attracting international innovation companies. For instance, IBM has already opened the East Africa innovation centre in Nairobi. This presents an EAC that is seen as taking the road to affluence and growth. However, as shown in the table below, the EAC is still far behind East Asia in terms of advanced sources of innovation. For example, the EAC still lacks advanced technologies in the field of aerospace, material science and chemical engineering among others.

Fig 1: Table 1: Selected sources of innovation in the East African Community and East Asia

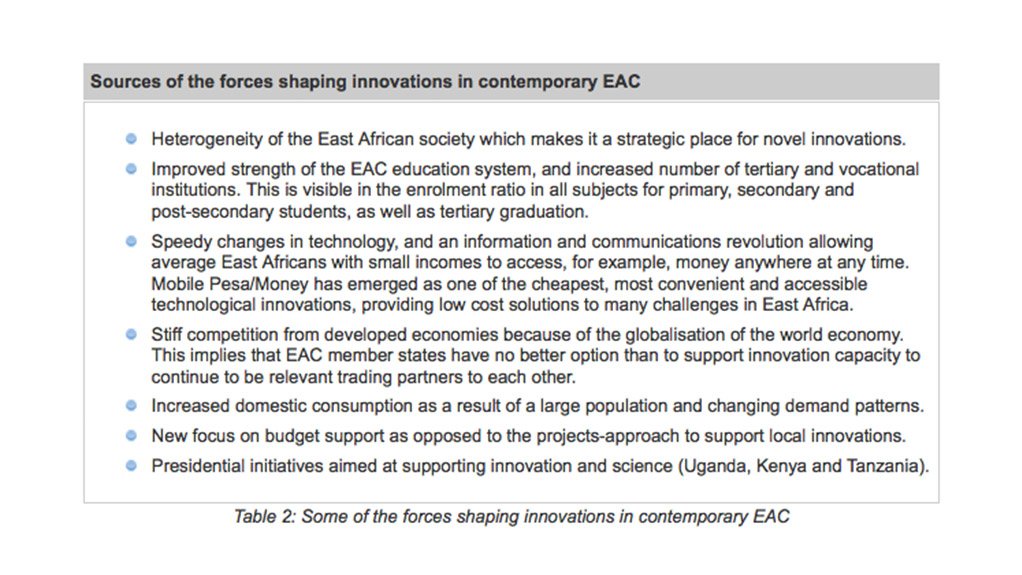

In view of Table 1 (see above), Table 2 (also above) shows some of the forces shaping the sources of innovation in contemporary EAC.

Fig 2: Table 2: Some of the forces shaping innovations in contemporary EAC

Will the EAC follow the East Asian development trajectory or its own?

Since the World Bank Policy Research Report The East Asian Miracle was published two decades ago, few specific studies have been conducted beyond East Asia to examine how innovation, priority infrastructure and foreign aid contributed to the East Asian development or created other direct and indirect spill-over effects related to economic development. Yet a proximate consideration of historical development trends reveals that innovation, priority infrastructure and foreign aid were crucial in contributing to the East Asian development. Now that the EAC member states have committed themselves to spending more than US$ 6 billion of their budget on priority infrastructure, innovation and science to maintain current economic growth, the question is whether the EAC will follow its own development trajectory or East Asia’s given the latter’s increasing aid support to the community’s priority areas and other economic involvements.

While East Asian lessons (on innovation, priority infrastructure and non-conditional foreign aid), and growing economic investments in the community are important for the development of the EAC, this does not necessarily imply that the EAC will follow the same development trajectory. There are five lines of arguments for this.

First, beyond Western countries, East Asia also had Japan as a leading industrial country and successful non-Western latecomer that played a catalytic role in providing favourable development aid and transferring technological innovations to fellow East Asian countries.(22) So far there is no single industrial country in the EAC.

Second, unlike the EAC, major East Asian countries (particularly Japan and South Korea) benefitted from the Cold War era politics. They were helped by and provided access to the large Western markets for their exports. This means that the West turned a blind eye to state-led development in East Asia to win allies. It is hard to imagine that the West will let EAC member states just adopt an East Asian development trajectory without causing any political, social and economic interruptions.

Third, as noted by Joseph Stiglitz, investments in the EAC and other African countries in general, unlike East Asian countries, have partly (or largely) been attracted by natural resources.(23) Unless the EAC invests much in strengthening the rule of law, human capital and protecting private property, the trajectory will be different.

Fourth, support for the United Nations Security Council resolution 1816 (2008) by the major powers (24) - particularly the US and EU - to internationalise the greater East African coast to curb the proliferation of piracy in the East African coast and the Gulf of Aden limits the EAC from following the East Asian development trajectory. East Asian anti-piracy campaigns were far less reliant on the navies, or “the roving squadrons of pirate-hunting vessels so central to American and European efforts and tended to focus more on circumstances on land, working to eliminate the root causes of piracy and to deprive potential pirates of motivation and means.”(25) This gave East Asian nations freedom to control their coastal shipping routes and saved them from trade containment and other dangers such as increased costs in the form of higher security service and insurance premiums and collective loss of trade revenue. Although piracy is causing considerable international trade deficits, the EAC is the most affected because it still lacks military and economic capacities to safeguard its shipping routes. Therefore, it is now unlikely that the EAC will follow the East Asian development trajectory when major powers (the US, EU, China, Japan, South Korea, India and Russia) have sent their navies to control East Africa’s lucrative shipping routes.

Fifth, the cultural difference between the EAC and East Asia is unmistakable. Much as it was possible for East Asian countries to adopt an industrialisation-oriented culture that later resulted in modernisation and development, it did not imply losing their cultures. For example, Japan, South Korea, and recently China, are industrialised but not totally westernised. Their capitalism is dissimilar to the Western version, and is constructed on different concepts of the individual. These nations took a few policies recommended by neo-liberal Washington and adopted ideas associated with “state sovereignty, economic wealth accumulation and technocratic rationalism,” but shaped their own development trajectory based on their cultures.(26) Similarly even if the EAC redoubles the focus on innovation and priority infrastructure and attracts more East Asian investments and aid, its development trajectory will still be characterised by the culture of Pan-Africanism which is the main linchpin and dominant ideology of the EAC and African people in general. Although undermined by the Western concepts of nationalism and state sovereignty, Pan-Africanism was born of over “five centuries of oppression, exploitation, domination, humiliation and indignity, visited on the African people by European imperialist powers.”(27) It is, therefore, imperative to argue that, through support for innovations and priority infrastructure, the EAC will follow the Pan-African development trajectory to reverse the impact of colonialism, and neo-colonialism with its associated policies that were designed, among others, to exploit Africans, their natural resources and sustain Western status quo.(28) The Pan-African development trajectory is one that that promises to lead to increased capacity of Africans to take full control of their destinies.(29) It embraces the Lagos Plan of Action that aims at the restructuring of the African economy based on collective self-reliance to reduce external dependence.(30)

Conclusion

Although innovation, priority infrastructure and foreign aid were some of the critical success factors in shaping the East Asian development, their presence does not provide enough evidence to justify a similar development trajectory for the EAC. This is because they did not stand in isolation of other factors, such as foreign direct investments, political stability, social integration, the role of the state and cultural mindset that equally contributed to the East Asian development.

What can be justified instead is that the development trajectory for the EAC is neither East Asian nor that recommended by neo-liberal Washington, but the Pan-African development trajectory, because it takes into consideration the realities and challenges in the EAC. In fact, the core challenge in the EAC is not lack of neo-liberal policy measures often recommended, but how to formulate policies that fit the local realities and environment.

Written by Ampwera K. Meshach

NOTES:

(1) Ampwera K. Meshach is a Consultant with CAI with a particular interest in the international relations of the East African Community and East Asia, Chinese and European Union foreign policies, development innovation and peace and conflict studies. Contact Ampwera through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Asia Dimension Unit ( asia.dimension@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Nicky Berg

(2) Juma, C., 2011. The new harvest: Agricultural innovation in Africa. Oxford University Press: USA.

(3) ‘Splits emerging within EAC bloc’, The New Vision, 26 October 2013, http://www.newvision.co.ug.

(4) ‘The economic development in Africa report 2013 - Intra-African trade: Unlocking private sector dynamism’, United Nations Conference n Trade and Development, 2 July 2013, http://unctad.org.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) 'An investment guide to the East African Community: Opportunities and conditions’, International Chamber of Commerce and UNCTAD, July 2005, http://unctad.org.

(8)Brahmbhatt, M. and Hu, A., ‘Ideas and innovation in East Africa’, The World Bank - East Asia and Pacific Region-policy research working paper 4403, November 2007, http://elibrary.worldbank.org.

(9) Yu, W., ‘Trends of trade flows of countries in the EAC and SADC regions and perspectives for the Tripartite Free Trade Area’, brief is prepared for the Task Force on Trade and Development of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, June 2012, http://um.dk.

(10) Programme for infrastructure development in Africa (PIDA) website, http://www.pidafrica.org.

(11) Tumushabe, W.G. and Ouma-Mugabe, J., ‘Governance of science, technology and innovation in the East African Community’, ACODE Policy Research Series No. 51, December 2012, http://www.ist-africa.org.

(12) Radelet, S., ‘A primer on foreign aid’,cCenter for Global Development working paper no. 92, July 2006, http://www.cgdev.org.

(13) Fukasaku, K., et al., 2005. Policy coherence towards East Asia: Development challenges for OECD countries. OECD Publishing: Paris; ‘Japan overview’, The World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org.

(14) Soesastro, H., 2005. “Sustaining East Asia's economic dynamism: The role of aid”, in Fukasaku, K., et al. (eds.). Policy coherence towards East Asia: Development challenges for OECD countries. OECD Publishing: Paris.

(15) Ibid.

(16) Coffey, P. and Riley, R.J. (eds.), 2006. Reform of the international institutions. The IMF, World Bank and the WTO. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham.

(17) Lyakurwa, W., 2005. “Sub-Saharan African countries’ development strategies: The role of the Bretton Woods Institutions”, in Teunissen, J.J. and Akkerman, A. (eds.). Helping the poor? The IMF and low-income countries. FONDAD: Amsterdam.

(18) Stiglitz, E.J., ‘East Asia’s lessons for Africa’, The Independent, 14 June 2013, http://www.independent.co.ug.

(19) Fourie, E., 2012. New maps for Africa? Contextualising the ‘Chinese model’ within Ethiopian and Kenyan paradigms of development. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Trento, Italy, http://eprints-phd.biblio.unitn.it.

(20) ‘Deepening and accelerating integration’, EAC Development Strategy (2011/12 - 2015/16), August 2011, http://www.eac.int.

(21) Mwapachu, J.V., ‘EAC experience, achievements, challenges and prospects: The dynamics of deepening regional integration’, paper presented at the 2nd EAC Symposium, Arusha, 28 April 2011, http://www.eac.int.

(22) Ohno, I., 2013. “An overview: Diversity and complementarity in development efforts”, in Ohno, K. and Ohno, I. (eds.). Eastern and Western ideas for African growth: Diversity and complementarity in development aid. Routledge: Oxford.

(23) Stiglitz, E. J., ‘East Asia’s lessons for Africa’, The Independent, 14 June 2013, http://www.independent.co.ug.

(24) ‘The situation in Somalia’, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1816, 2 June 2008, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org.

(25) Clulow, A., 2009. The pirate returns: Historical models, East Asia and the war against Somali piracy. Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 25(3), pp. 1-11

(26) Mushakoji, K., 1997. “Japan and cultural development in East Asia - Possibilities of a new human rights culture”, in Plantilla, J.R. and Raj, S.L., (eds.). Human rights in Asian cultures: Continuity and change. Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center: Osaka.

(27) Shivji, G.I., ‘Pan-Africanism and the challenge of East African Community integration’, Pambazuka News, 3 November, 2010, http://www.pambazuka.org.

(28) Katembo, B., 2008. Pan Africanism and development: The East African Community model. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2(4), pp. 107-116.

(29) Adogamhe, G.P., 2008. Pan-Africanism revisited: Vision and reality of African unity and development. African Review of Integration, 2(2), pp. 1-34.

(30) Sekgoma, G.A., 1994. The Lagos plan of Action and some aspects of development in Sierra Leone. Pula: Botswana Journal of African studies, 8(2), pp. 68-94.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here