Over the last week, President Jacob Zuma and his supporters have experienced dramatic reversals of fortune. These setbacks have been partly in the courts, with the withdrawal of the fraud and theft case against Pravin Gordhan and others who had been associated with SARS.

Together with the withdrawal of the case against Robert McBride, these decisions may also presage the collapse of charges against former Hawks generals Anwa Dramat and Shadrack Sibiya. Both the Treasury and the Hawks under Dramat safeguarded state wealth against looting. Had there been successful prosecutions, it would have weakened defences against stealing state resources and “state capture”.

The president’s attempted interdict against the release of the former Public Protector’s state capture report has been withdrawn. It will be released too late to make an adequate assessment of its contents here. From what appears in the introduction, its release may provide further evidence of the extent of influence of the Gupta family on affairs of state, but also point to additional levels of corruption in government, that were previously unknown.

Calls for Zuma to resign are gathering in a range of quarters and now derive from many who have previously been silent, including some involved in his rise to power or closely allied, as with unions like NEHAWU, now the largest affiliate of COSATU.

But it is not easy for Zuma to make a dignified exit. Relinquishing the reins of power immediately creates dangers for him. There are many examples in history where a once powerful leader on leaving office is held accountable for various misdeeds committed during his incumbency. There are many alleged deeds or known misdeeds committed by Zuma, and possibly many others we do not yet know about.

These include the 783 charges of fraud, corruption and racketeering against the president, which could well be returned by the SCA for prosecution in the near future. A week ago it would have been a foregone conclusion that the NPA would find a way of delaying or avoiding a decision. But the aftermath of the failed prosecution of Gordhan has left the NPA’s reputation in shreds, and it may be difficult for it now to avoid prosecution unless there is some extraordinary and legally sound reason.

Once Zuma goes it may be that other misdeeds will be uncovered. We may also find that there is a revisiting of the full extent of the Nkandla misuse of state funds and other cases where litigation might be instituted to recover further enrichment.

The court decision over Zuma’s attempt to interdict the Public Protector’s report, which calls on him to demonstrate why he should not personally meet the legal costs, addresses an urgent need to end the apparently interminable spending of huge sums of state monies defending cases where there has been no real case to argue.

Zuma rose to power in the wake of the apparent unpopularity of former president Thabo Mbeki, who was depicted as aloof, secretive, tending to centralise authority, and unsympathetic to problems of the masses. Zuma, in contrast, was depicted as pro-poor and even socialist in inclination, by the SACP and COSATU, even though they knew his political record did not support this.

When Zuma became president most sections of business and many other leaders of civil society cautiously welcomed his election. That support has now dissipated, with large numbers of business leaders signing petitions for his resignation and numerous ANC veterans and organisations of civil society calling for him to step down.

Assuming that Zuma goes, which he ought to be made to do, we need to clarify what political conditions need to be created in the aftermath. There may be agreement that constitutionalism should be restored but is there broader agreement on what needs to be remedied?

Insofar as many who now call for Zuma to resign brought Zuma to power or served under Zuma, what must be allowed to stand and what do they now believe must be remedied? Was everything in order, apart from the Nkandla scandal and whatever emerges in the state capture report? Do we not need more introspection into what the qualities of the Zuma era have been in order to rebuild our democratic order? Also, can those who speak of returning the ANC to its “true self”, legitimately assume that everything that preceded Zuma needs no revisiting?

One of the lessons of the Zuma era is that even the most progressive constitution in the world can be undermined if there is no counter-balancing force. Some see the counter balance in the separation of powers doctrine, and that is valid. It is true that the courts have sometimes been a counter balance to other institutions of state. But that does not cover defiance of legality, which is not brought to book and cannot easily be remedied. To reach court, let alone the Constitutional Court requires funding, and even where there is a court decision, its implementation relies on good faith and is often found wanting.

Do we not need to look to the power of people brought together in various types of organisation as a key way of holding individuals accountable, but also playing an active role, as citizens, in regenerating South African democracy?

There were organised structures in exile and in military camps from the 1960s. These were obviously not the same as that where an organisation relates to its core constituency, as when communities are organised to prevent mining or mining profits being diverted by a traditional authority, or where they resist land dispossession in the rural areas, or when shack dwellers in the cities organise themselves to prevent eviction, or HIV activists campaign for antiretrovirals.

In the 1980s the UDF (and also outside the UDF, independently or affiliated to other political tendencies) there were a number of social movements organised around a range of sectors. They often also united within a broader political opposition movement, which the UDF became, that was a major factor in the ending of apartheid.

Some trade unions were affiliated to the UDF, some to other political tendencies like the Black Consciousness Movement or PAC and others remained politically independent. The unions were then mainly organised on the shop floor, something that has declined with the diminished power of industrial unions compared with public sector ones.

What distinguished that period from today is that those who were engaged in political struggle in organisations of various persuasions were involved in continual and lively political debate. With the rise of patronage politics and the politics of spoils, that intensity of political contestation has disappeared from much of our politics, which has come to relate more to personalities and those attached to powerful individuals.

Business was also organised around its own interests, albeit not in one organisation. But it has always had some capacity to exercise influence on the political sphere, either through organisations, or informal contact with government.

At this time business has the clout to be able to play an important role in support of democratic revival. It has intervened over specific issues, but it ought to have a more general interest in acting to support re-creating a framework for democratic politics. At the same time as it enters this sphere of democratic politics it must accept that many of the assumptions that most sections of business accept as “given” are likely to be subjected to challenge as part of a national debate.

One of the features of the period since 1990, and especially since 1994, has been the diminution of the power of “organised forces on the ground”, that is, social movements. Many actors believed that such organisations were not needed with the return of the ANC from exile and Robben Island and they, like the UDF itself, were dissolved. Some in the ANC supported their disappearance because one of the features of the national liberation movement model of politics is a tendency to see that movement as embodying “the national” and being intolerant of organisations outside of its fold.

An emancipatory politics will not automatically arise from the removal of Zuma, should that happen. It needs to be built. How is that to be done? There has to be a return to the hard and slow task of building organisations, in a number of places and sectors. That may sound old-fashioned to some, but it is essentially very democratic and also a way of building what is a sustainable way of conducting democratic politics.

Building an emancipatory movement, a movement that can restore the country to a democratic path and revive confidence in our future, is not achieved simply by finding a leader with integrity. It needs to be underpinned by structures grounded in communities, factories, professions, businesses, educational institutions, places of worship and other locations of organisation.

One thing we learn from the period under Zuma is that one needs a leadership that does not rely on the qualities of any single individual but an organised power that influences political activities on structured lines and also imbues the state with an emancipatory ethos and with integrity. It also needs to be infused with a vision and political ideas that are liberatory.

There are some who may read this as someone writing on the basis of a romanticised view drawn from experiences in the 1980s. It is true that I believe that some of what happened in the popular power period of the 1980s needs to permeate our thinking about the future, a future where we all need to have a role in building and safeguarding our democratic gains.

The current conditions of the country require urgent attention. But it is precisely because of the seriousness of the present situation that we need to build solid foundations, not rushing, but carefully discussing and considering the way forward in an inclusive and non-sectarian manner.

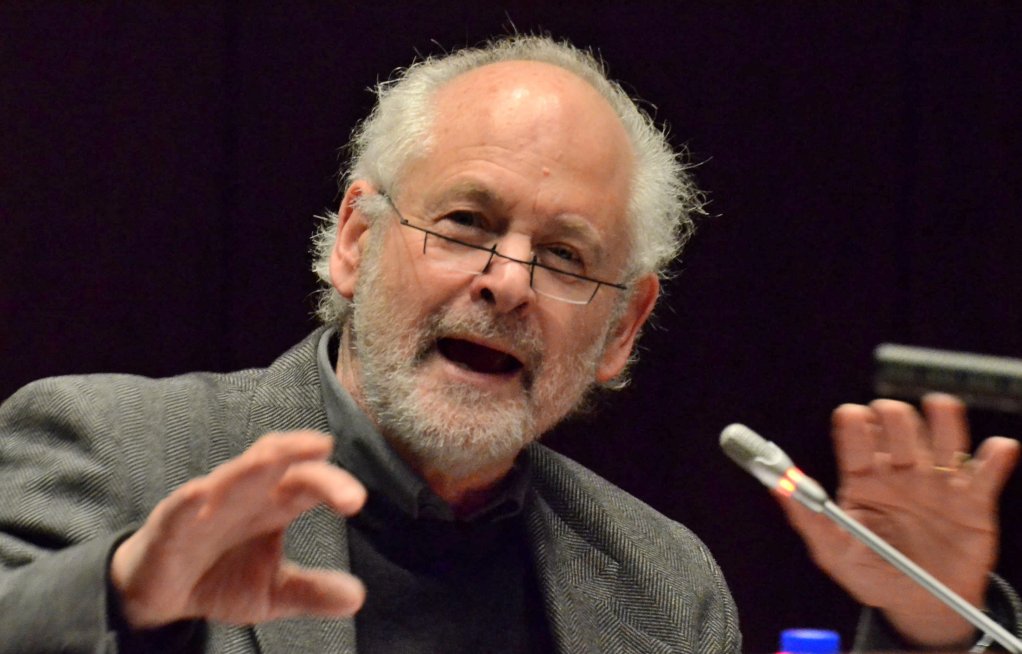

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. He is a former political prisoner for activities in the ANC-led liberation struggle. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes University and an Emeritus Professor at UNISA. He has published extensively on Chief Luthuli in scholarly journals and essays in his recent book, Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana and Lynne Rienner, 2015). He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here