One of the most troubling features of contemporary South African politics is the retreat of the ANC from its liberation past. That past was often one where the organisation, its leaders and members came from oppressed communities and embraced their sorrows and hopes as their own.

Under apartheid it was obvious that the government and state lacked legitimacy. Both were founded on violence and represented only whites. The apartheid regime operated under a racist constitution and perpetrated acts of discrimination and violence against the majority of the population. In the words of the Freedom Charter, “our people have been robbed of their birthright to land, liberty and peace by a form of government founded on injustice and inequality”.

White rule over blacks took a range of forms over the centuries, including colonial and then apartheid rule. What was common was that they always lacked consent and wreaked considerable damage on the wellbeing and life chances of black South Africans.

Many of those who joined the struggle for liberation did so because they witnessed violence and harm perpetrated against their family or experienced it themselves. Many describe their political awakening in relation to having witnessed the humiliation of their parents or harm done to a child or a sibling by apartheid authorities.

The promise of liberation entailed a pledge to remedy a situation where black people were denied the range of freedoms owed to any human being by virtue of being a human person. Liberation promised a commitment to create a state where all could stand tall, without humiliation, and proudly enjoy their rights and realise their talents.

In joining the struggle for liberation those who committed themselves as cadres, those who sacrificed the most, joined their fate, their consciousness and their understanding of selfhood with that of all oppressed people. In their minds they fused their own future as individual human beings with that of the rest of the people of the country. They did not lose their character as unique individuals, but they enlarged their understanding of their own humanity by taking on, as the burden of their life, that of all.

They did not try simply to remedy individual problems, as one might do by embarking on litigation or through an individual appeal against a bureaucratic decision, or by talking to some person in authority. These were not eschewed. But it was recognised that apartheid did not simply comprise individual experiences of ill will against particular people, though it was individual human beings who suffered greatly as specific human beings. Apartheid also had a systemic effect on the life experiences of all oppressed people.

In trying to bring apartheid to an end, freedom fighters connected their own fortunes with those of all oppressed people, aiming to remedy the injustices they experienced because of being black people.

In some cases those who joined this liberation movement were from the poorest of the poor, like Walter and Albertina Sisulu, and Chris Hani. There were also some who were trained as or later became professionals, like Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, or later received university education like Chris Hani. And there were whites, some of whom were trained as professionals like Joe Slovo, Bram Fischer, and Ruth First.

All decided to merge their own lives with that of the majority of the people of South Africa, even though they knew that they would potentially suffer harm and even forfeit their lives, as happened in the case of First, Fischer, Hani, Steve Biko, Johannes Nkosi, Ahmed Timol and Dulcie September, amongst many others.

There is little doubt that the living conditions of the majority of South Africans have improved substantially since 1994. But the trajectory of democracy and transformation have come to be conceived in at least two ways. In the first place, through state action, there has been redress and development aimed at the poor, who have seen improved housing, health care, water and education, albeit in uneven degrees and sometimes unsustainably. The provision of social grants has lifted some people above absolute poverty and there have been various other improvements.

But there has also been a resort to individual and community redress. Though the constitution and law of post-apartheid South Africa is no longer a rights-denying, but now a rights-bearing law, many have been forced to achieve their rights through the courts. Important gains have been made through litigation and these must be safeguarded, while we should note that court action by its nature is expensive and hard to access.

But for those with power and wealth there has been a rethinking of their relationship to social improvement and their conception of what post- apartheid South Africa ought to mean. Individuals who may or may not have had a significant record in the struggle have come to act as bearers of that legacy and deploy that in a quest for improvement in their personal conditions. In doing so they now interpret the goals of political activity of the previous liberation movement, its one-time communist party and once proud trade union movement not as being to benefit all but rather to enhance the life opportunities or increase the already transformed life chances of the few who are close to power or derive benefits from those who hold power.

Insofar as this interpretation of liberation encompasses a very limited range of people - though they may derive from oppressed communities – it excludes large sections of the oppressed population from benefitting sufficiently.

It fails to adequately remove the legacies of apartheid from the shoulders of the most oppressed, even where such action is within the power of those in authority. This happens through diverting funds intended for the many to the benefit of the few, as was the case with the Nkandla expenditure, and other instances of redirection of resources away from the poor.

We need to unpack what it means when the very same cadres who sacrificed (along with some who did not but now link their fates with them or claim to have “been there”) vote in favour of irregular expenditure. When they do that they benefit the people who have the power to secure their own future advancement for the moment. That is a patronage relationship, of course.

But the people who do this often derive from the poor. They perform these acts at the expense of those for whom and with whom they joined the struggle in the first place.

What we see happening is a break in the trajectory of the lives of those whose previous self-conception was or purported to be connected with the fate of the majority. Insofar as resources were intended to benefit their parents or the equivalent of their parents, their children, their siblings or those like them, that money is now diverted from those who were once their own or considered as that.

This rerouting of resources in the interests of those who hold power over the majority of people who live in abject poverty represents not only a rupture. It also represents a continuity of the dispossession and marginalisation of the poor.

Any substantial programme of social transformation needs “buy in” from capital. Where the government of the day diverts funds in this way, it does not itself have the integrity to question the accumulated wealth and indifference to the plight of the poor on the part of big capital. If government is not prioritising these people, what right does it have to demand that of the private sector? One of the tragedies of the present is that the ANC-led government has become a part of that which they purported to want to change.

When people protest against the failure to meet their basic needs or, more recently, for equal access to education, they meet violence. These recipients of violence, encountering stun grenades, rubber bullets and clubs could well be the parents or the children of MPs.

Now it is no longer the apartheid state that is meting out violence. But it matters little when one looks on the ground and sees that those who are dead or maimed come from the same section of the population who were killed or injured under apartheid.

Normally we would attribute unquestioned legitimacy to a state and government that has been duly elected in free and fair elections and one needs to act with care before one impugns such legitimacy. Yet, even as this government is elected by universal suffrage, can we shrink from questioning whether its anti-popular actions undermine any claim to legitimacy, whether or not it enjoys an electoral mandate?

There is a sense in the minds of many that there is no viable alternative to the present rule by violence and looting. But this year has seen some important movements for change, notably, though their character and results have been diverse, the student protests. Whatever its problems, this movement has initiated a process that has reopened important debates and is still unfolding. It is important that we try to build on this momentum to develop a common vision that can guide us towards recovering a humanistic vision embracing freedom for all.

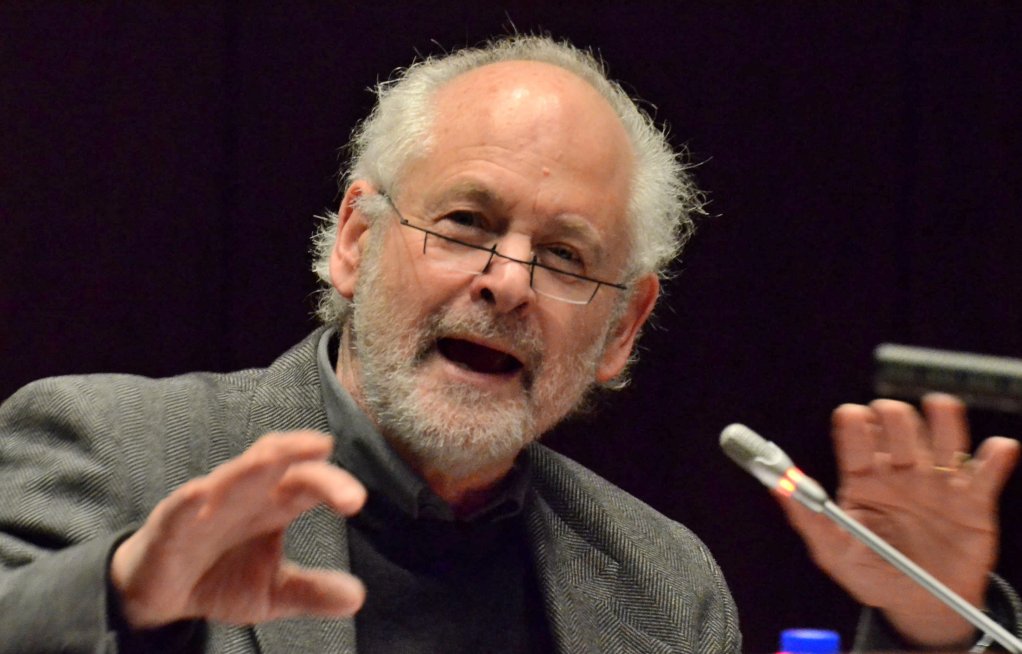

Raymond Suttner is a professor attached to Rhodes University and UNISA. He is a former ANC underground operative and served over 11 years as a political prisoner and under house arrest. He writes contributions and is interviewed regularly on Creamer Media’s website polity.org.za. His most recent book is Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana Media and Lynne Rienner, 2015). His twitter handle is: @raymondsuttner and he blogs at raymondsuttner.com.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here