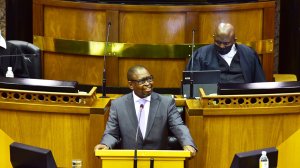

Minister of Finance Enoch Godongwana has a golden opportunity in his Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) to come clean on how much the National Health Insurance (NHI) is likely to cost.

Ordinary South Africans will be the ones funding the NHI and have a right to know what the bill is going to be.

The Institute of Race Relations (IRR) has been arguing for some time that the NHI is unaffordable. The country’s fiscal position simply does not allow for the implementation of the scheme. Consider that the National Treasury also revealed a few months ago that the budget moved to a monthly deficit of R143.8-billion in July. This is the largest deficit since 2004.

Additionally, Minister Godongwana warned last month that South Africa’s public finances are in a poor state, with the government failing to meet its tax-collection targets, and tighter financial conditions making it difficult to borrow more at affordable rates. The mounting government deficit has also led to a significant increase in the national debt over the years. This has been exacerbated by the mini-commodity boom coming to an end, after having saved the country’s fiscal bacon in the past year. That windfall has now come to an end, however.

In an address in Cape Town last month, the First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Gita Gopinath, warned that South Africa’s interest bill on its growing public debt could triple the size of its health budget within five years, and it projects that the cost of the government’s debt will rise from 19% to 27% by 2028.

The Department of Health has claimed that ‘South Africa’ spends 8.5% of GDP on healthcare. This is simply not true. Rather, it is the country’s taxpayers that provide the substantial revenues, amounting to 4.1% of GDP, that are spent on public health every year. Many of those same taxpayers then pay out of their own after-tax income for the private healthcare of their choice, spending some 4.4% of GDP on this.

The high costs of private healthcare are also partly because of government regulations. These costs could be significantly reduced. Private healthcare would be significantly cheaper – and thus accessible to many more people – if state regulation had not so pushed up the costs of medical scheme membership since 1998. In addition, if the government was willing to allow low-cost medical schemes costing some R200 per adult member per month, as proposed by the Council for Medical Schemes in 2015, some 15-million more South Africans would already have access to private healthcare at the key primary level.

The costs of NHI have also simply never been properly quantified, but they are likely to be very high. Former Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize told Parliament in August 2019 that it would not be enough to combine the amount being spent on health in the public sector (R220bn in 2019/20) with the amount being spent in the private sector (R250bn in this financial year) as a higher annual sum would be needed. This means that tax will need to increase, possibly significantly.

The tax increases required to generate the at least R470bn a year (and more likely R700bn a year by 2026) will be high. The burden of new payroll taxes (at a rate of at least 3%), surcharges on income tax (also at rates of at least 3%), and higher VAT rates (at an extra four percentage points or more) will fall heavily not only on the middle class but also on the poor.

In addition, much of the revenues raised in this way may not be used for the NHI at all – as the ‘ring-fencing’ of these monies will require a separate statute the National Treasury is reluctant to enact. The initial tax burden may thus increase by 66% (in real, or after-inflation, terms) over the next 20 years, as has happened in Canada with its ‘single-payer’ system.

South Africa already has one of the highest tax burdens in the world, while its tax base is very small. In addition, its public debt, including government guarantees to Eskom and other state-owned enterprises (SOEs), already stands at some 80% of GDP. The government thus needs to reduce state spending and cannot increase it in the way the NHI will require.

The National Treasury warned in its October 2019 MTBPS that NHI costs are ‘no longer affordable’, given the country’s current ‘macroeconomic and fiscal outlook’. This echoes an earlier warning by the Davis Tax Committee, which stated in 2017 that the NHI was ‘unlikely to be sustainable’ without faster economic growth, which has not transpired and is unlikely to be achieved. It is irresponsible for the government to press on with the NHI in the face of these important warnings.

And the IRR is not the only body raising the alarm.

A few weeks ago, Ashburton Investments flagged the NHI as one of the domestic factors posing a risk to the government’s balance sheet. This is another indication that the NHI is unsustainable.

It is also worth noting that Discovery, whose CEO Adrian Gore, previously described the NHI as necessary and morally correct, has recently listed the NHI as the second-biggest risk facing it.

The National Treasury’s silence on the details surrounding the costs of the NHI is concerning. The IRR will continue to apply pressure on Minister Godongwana and the National Treasury to disclose the costs of the NHI, as it is a matter of public interest. In fact, it is not an exaggeration to say that the high costs of NHI could be the source of an existential crisis in the financial sustainability of the South African state.

Written by Mlondi Mdluli, Campaign Manager at the Institute of Race Relations

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here