The toppling of Jacob Zuma and Robert Mugabe and events in Angola may have created a glimmer of hope for long-suffering Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where one of the world’s gravest but least reported humanitarian crises is worsening because of President Joseph Kabila’s repeated refusal to step down.

The United Nations (UN) last October gave the DRC, Africa’s second largest country, its highest disaster classification, on a par with Syria and Yemen, with which it vies in a dismal league of global catastrophes.

Yet a survey of international aid agencies by the Thomson Reuters Foundation showed DRC was the most neglected crisis of 2017.

Earlier this month, the UN said the number of people fleeing their homes in DRC doubled over the last year to 4.5-million and 13-million people needed assistance. Some 4.6-million children were acutely malnourished.

Conflict has continued in eastern DRC for two decades, since “Africa’s world war” following the overthrow of kleptocrat dictator Mobutu Sese Seko sucked in nine national armies and killed more than five million people.

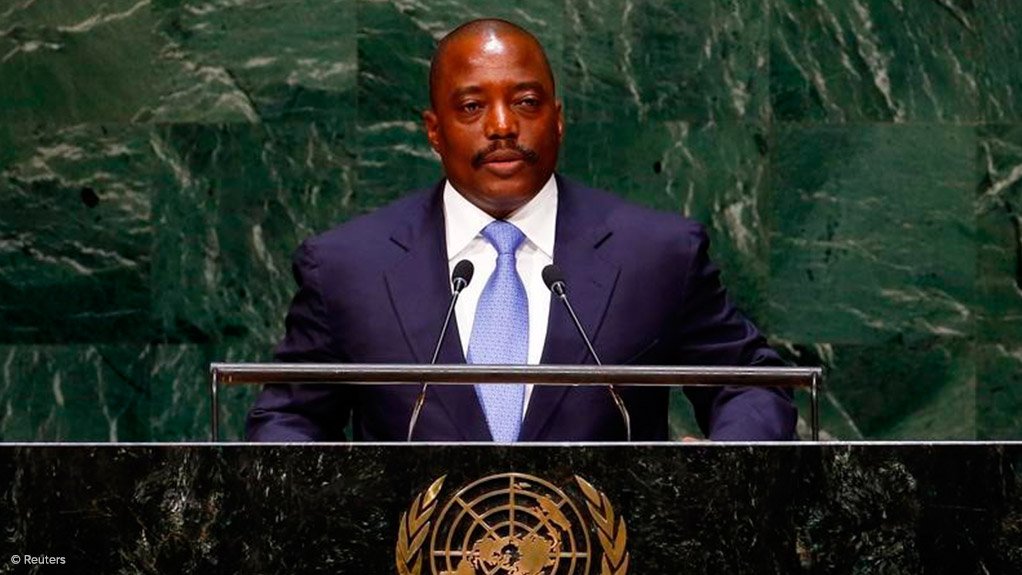

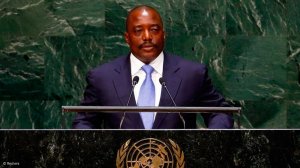

But recently violence has surged elsewhere, some of it in previously peaceful areas, because of the refusal of Kabila, 46, to step down when his constitutionally-limited two terms ended in 2016.

LOCAL CONFLICTS

In the absence of effective government or security in much of the country, local and ethnic conflicts have proliferated, fuelled by rage at state neglect and poverty despite fabulous mineral riches. There are now around 120 rebel movements compared to 42 in 2012.

In the central region of Kasai alone, which had escaped endemic violence until a brutal conflict broke out in 2016, 5 000 people have died, and 400 000 children are acutely malnourished, about the same as in Yemen.

A scheduled election was originally postponed until the end of 2017 and then again until December 23 this year, ostensibly because of logistical problems in a country almost the size of Western Europe that is largely devoid of infrastructure.

Two senior ministers said recently that Kabila will not stand for re-election, but many of his countrymen believe he wants to change the constitution to enable a third term. The electoral commission has said the poll could be postponed again until April 2019.

Kabila, a former rebel commander who took power after his father was assassinated in 2001, is rarely seen in public. But with the opposition deeply divided, he has played his hand with skill, working through personal alliances with army commanders.

Security forces have cracked down on dissent, often led by the Roman Catholic Church, and more than 40 people were killed in protests last year.

The DRC, which has not had a peaceful transfer of power since independence in 1960, is still being plundered as it has been since Belgium’s King Leopold seized the area and turned it into a genocidal, money-making enterprise in the late 19th century.

Last year, a Global Witness report said a fifth of DRC’s mining revenues had been lost to corruption between 2013 and 2015.

KABILA LOSES ZUMA’S VITAL SUPPORT

Hopes for change may rest with southern African powers that once backed Kabila.

Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe, a Kabila ally, was overthrown last November. But more importantly, the demise of South Africa’s Jacob Zuma last month removed one of his staunchest and most powerful friends, who had shielded him from accusations of human rights violations.

It remains to be seen, however, how soon President Cyril Ramaphosa can turn his attention to regional issues like the DRC, given his multiple domestic problems.

There has also been a cooling of relations between DRC and Angola, which had been one Kabila’s key military allies for decades.

Like other regional powers, Luanda appears to be losing patience with the dangerous instability caused by Kabila’s refusal to step down, which has spilled over their border in the form of tens of thousands of refugees from the Kasai conflict.

Angola withdrew military trainers from DRC in December 2016, and the chilling in relations with Kabila could accelerate under new President Joao Lourenco.

Another of Kabila’s powerful traditional allies is China, which has huge investments in DRC, the source of most of the cobalt for its mobile phone and electric vehicle industries. Kabila’s opponents hope Beijing will withdraw support if instability threatens its investments.

Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi on DRC’s eastern frontiers are unlikely to object to Kabila trying to extend his term since their leaders have already done so and they have greatly profited from cross border trade.

However, instability and conflict in DRC, provoking thousands of refugees to cross the borders, may mean this support has limits.

The fate of benighted Congo may depend less on what happens in Kinshasa than on a regional shakeout following political changes elsewhere.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here