The colonisation by the United Kingdom of many African countries in the late 1890s and early 1900s resulted in the redistribution of wealth in favour of expatriate classes of the colonised societies whilst marginalising indigenous people. However, upon attaining political independence, most former British colonies on the continent did not address this wealth imbalance as the new governments feared being seen as embarking on retribution missions, which would result in the flight of capital needed for economic recovery. A number of countries have subsequently embarked on affirmative action programmes, commonly known as economic empowerment policies, to address the imbalances.(2) However, some of these empowerment policies tend to counteract the interests of foreign investors and, hence, the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) into these African nations. FDI is important in that it allows a country to acquire new technology and skills and to create new employment, which is critical to the growth of any economy.(3) This discussion paper examines the impact of empowerment policies on FDI flows in three selected African countries, namely Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Their geographic proximity in Southern Africa notwithstanding, these countries have been selected based on their unique and diverse approaches to economic empowerment.

What are economic empowerment policies?

Botswana’s citizen economic empowerment policy defines such policies as a “set of inter-related interventions aimed at strengthening the ability of the indigenous or citizens of a country to own, manage and control resources, and the flexibility to exercise options, which will enable the native of a country to generate income and wealth through a sustainable, resilient and diversified economy.”(4) Such empowerment could not, however, be achieved during colonial times as native populations’ participation in economic activities was limited to being providers of labour rather than owners of capital. Hence, wealth distribution was skewed in favour of the colonial expatriate. Most economic empowerment programmes in Africa aim to redress economic imbalances created by past colonial experiences. In most countries, the decolonisation process left economic power with minority ethnic groups, excluding the majority of African populations from participating in the mainstream economy. Therefore, economic empowerment policies aim to create an environment that enables citizens to take better advantage of economic opportunities and the economic growth process. For example, the rationale for South Africa’s Black Economic Empowerment Act of 2003 is to promote economic transformation in order to enable meaningful participation of black people in the economy.(5)

Nature of empowerment policies in Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe

The Botswana citizen economic empowerment policy has its inception in 1999. The policy emanated from the National Conference on Citizen Economic Empowerment which called for the exclusion of non-citizens from participating in certain economic enterprises and the need to lower costs for citizens to go into business.(6) The policy is not enacted in a single act or law but is embedded in various laws, which were enacted over time to enforce participation by Botswana citizens. These laws are: the Industrial Development (Amendment) Regulations Act of 2008, which reserves small-scale manufacturing for Botswana citizens or companies wholly owned by Botswana citizens; the Trade Act of 2008, which reserves retail services for entities with less than 100 employees; the Liquor Act of 2003, which reserves liquor bars, night clubs and bottle stores for citizens, and the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act of 2001, which gives preferential treatment to Botswana citizens or companies wholly owned by Botswana citizens in state procurement processes. Joint ventures in the reserved activities are permitted with up to 49% foreign participation, subject to approval by the Minister of Industry and Trade. The citizen partner holds a minimum of 51% shareholding.(7) The Botswana empowerment policy is limited to facilitating access to financial resources and ownership of assets and lacks enforcement to maximise participation of its citizens in economic activities.

In South Africa, the government implemented Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) in 1994 with a view to advance economic transformation in order to enable the participation of previously marginalised communities in the economy, thus changing the racial composition of ownership and management structures and of existing and new enterprises.(8) The initial BEE programme was heavily criticised as it benefited mostly individuals who were politically connected through equity transfer. A BEE commission was established to devise recommendations to review the BEE policy, culminating in a revision of the existing policy in 2004. This resulted in the implementation of an inclusive Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Strategy (BBBEE), which instead emphasises the involvement of black people in economic activities through skills transfer and government procurement, rather than a narrow focus on assets transfer. The Department of Trade and Industry is tasked with implementing, regulating and enforcing compliance with the laws and makes use of a ‘balanced scorecard’ to measure progress towards BBBEE compliance by enterprises. The scorecard measures three core elements of BBBEE, namely: direct empowerment through ownership and control of enterprises and assets; human resource development and employment equity; and indirect empowerment through preferential treatment in procurement processes. Although the scorecard is the standard for measuring BBBEE compliance, sector-specific charters have been developed for industries such as mining, financial services and tourism.(9)

In Zimbabwe, a land reform programme was formally implemented in 2001 but farm invasions started informally early in 1998 in the countryside, led by landless villagers. Reforms were based on the need to eradicate poverty and further economic development. With agriculture being the cornerstone of the country’s economy, land is regarded as the engine for economic growth. The Zimbabwe Government passed the Land Acquisition Act of 1992, freeing it from compensating farmers under the willing seller–willing buyer clause in the Lancaster House Constitution, which forbids compulsory acquisition of land by the government.(10) Due to slow progress in the willing seller–willing buyer process, the government embarked on fast-track land reform aimed at decongesting communal lands and creating an indigenous commercial farming sector. It designated a number of white-owned farms for compulsory acquisition, excluding farms owned by indigenous black people, churches, plantations or those with permits from the Zimbabwe Investment Centre – now the Zimbabwe Investment Authority (ZIA). These permits give investors special treatment and protection from changes in government policies.(11) The other core aspect of Zimbabwe’s empowerment agenda is the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act (IEEA) of 2007, which mandates all companies operating in Zimbabwe to secure 51% ownership of shares by indigenous Zimbabweans through partnerships with business people, community share trusts and worker share trusts. The law was implemented in 2010 and firms in the mining sector were given 45 days to comply.(12)

Foreign investor concerns about empowerment policies

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe noted in 2009 that the establishment of property rights and their enforcement was critical in attracting investment in any economy.(13) Foreign investors become concerned with empowerment programmes, in particular, when they encroach on private property rights. A violation of property rights entails an assault on the right to tenure or entitlement. Some economic empowerment programmes have been viewed as appropriation and most investors view them with suspicion, adopting a wait-and-see attitude towards investing in the host country for fear of losing their investments.(14)

Policies dealing with foreign investments need to be transparent and predictable as this helps foreign investors to be well informed on a timely basis before they commit to investments. In economies in which economic empowerment programmes are not transparent or predictable, foreign investors are hesitant to invest until they are clear about the objectives of the policies and are certain that security of their investments is guaranteed. An economic empowerment programme has to be drafted using plain language to guarantee transparency and avoid ambiguous meanings via different interpretations.(15)

Analysis of FDI flows before and after implementation of economic empowerment

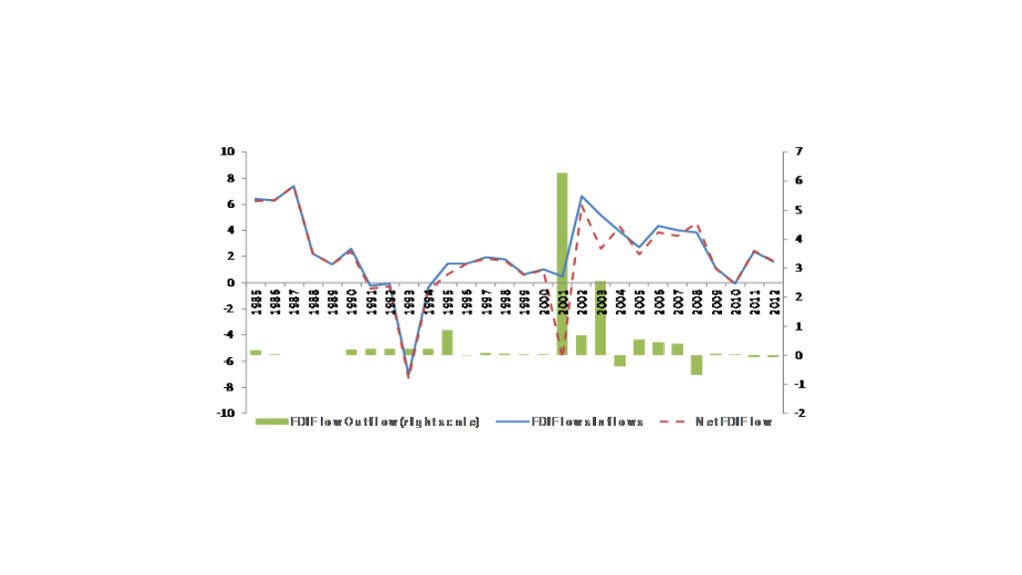

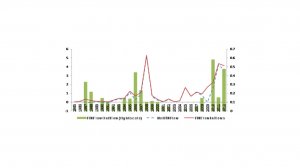

Botswana has given no precise date for the implementation of its economic empowerment programme, enacted over time since 1999 in various law and statutes, as mentioned. Thus, this paper focuses on the period before and after 1999 to analyse FDI flows to and from Botswana. This paper’s analysis of data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that Botswana’s net FDI averaged 1.65% of gross domestic product (GDP) between 1985 and 1999 and 1.99% of GDP between 1999 and 2012.(16) Figure 1 shows that the implementation of Botswana’s citizen economic empowerment policy does not appear to have made a significant impact on the flow of FDI in and out of the economy.

Figure 1: Foreign direct investment flows, Botswana, 1985–2012 (% of GDP) (17)

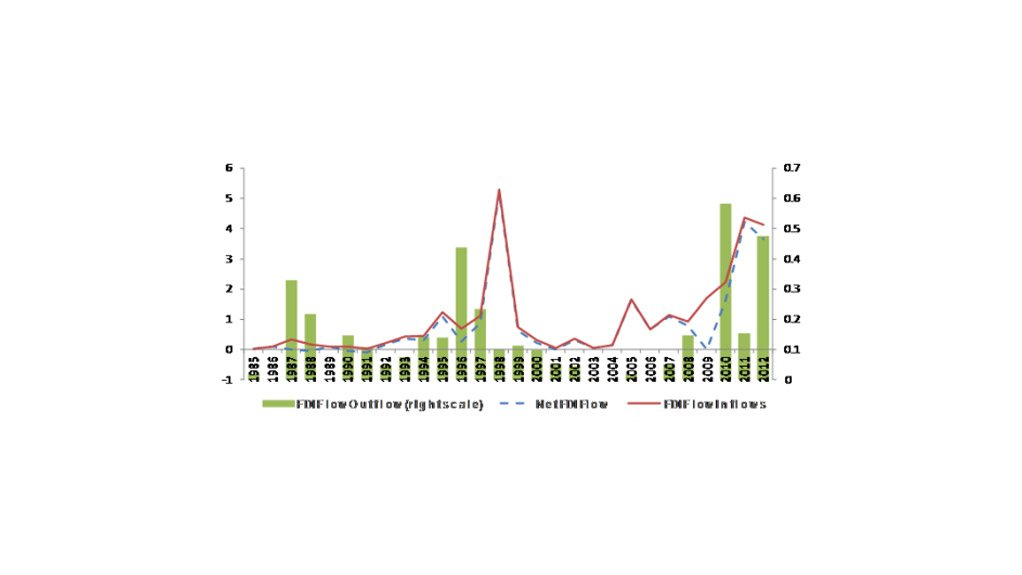

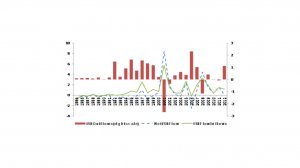

In Zimbabwe, net FDI grew steadily at an annualised 0.24% of GDP between 1985 and 1998. After a 1998 peak, investor confidence was shattered by the fast-track land reform programme that nationalised private land in violation of private property rights; this resulted in FDI flows into Zimbabwe declining by on average 0.55% a year between 1999 and 2009, after which they started to show significant recovery (see Figure 2).(18) However, the government of Zimbabwe thereafter enacted and implemented another economic empowerment policy, the IEEA programme. FDI inflows to Zimbabwe between 2010 and 2012 have not reacted significantly but there has been a significant increase in FDI outflows because the law, when enacted, lacked clarity on the protection of property rights.(19) As Figure 2 shows, Zimbabwe’s economic empowerment programmes appear to have had a significant impact on FDI flows in and out of the country in the period immediately following land reform, with a particularly drastic decline in FDI inflows. The impact of the IEEA policy is seen as follows: FDI outflows increased from 0.05% of GDP in 2007 to 0.47% of GDP in 2012 as investors feared losing their investments to a policy reminiscent of the land reform programme.(20)

Figure 2: Foreign direct investment flows, Zimbabwe 1985–2012 (% of GDP) (21)

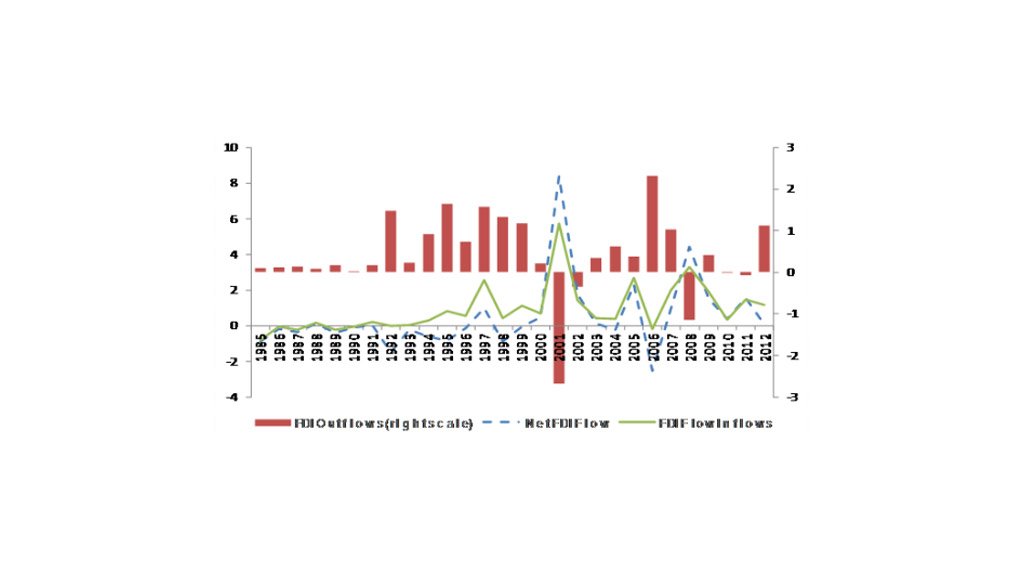

In South Africa, net FDI started to show significant growth in 2001, having been constant in particular in the period under apartheid. Net FDI flows increased gradually after 1994, averaging 0.91% of GDP between 1994 and 2003 in response to stable economic fundamentals, whilst FDI outflows increased from 0.91% of GDP in 1994 to 1.19% in 1999. The outflows resulted from some South African firms opting to invest in other countries following the removal of UN sanctions on the free flow of funds from and into apartheid South Africa, but were also partially due to the nature of the initial BEE policy that put much focus on asset transfer (see Figure 3). Because the policy was heavily skewed in favour of political elites, the policy was revised and a new law, the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) Act, was enacted in 2004 following recommendations made by the BEE commission in 2001. Thereafter, FDI inflows declined to 0.36% of GDP in 2004 while FDI outflows increased to 0.62% of GDP in 2004. This resulted in a decline in net FDI to -0.25% of GDP, which later increased in 2008 amid a positive response to the outcome of national elections and the new government’s commitment to protect investor interests.(22) Between 2008 and 2012, net FDI again declined in response to the global economic crisis.(23) For South Africa, foreign investors appear to have responded positively to an inclusive empowerment programme that adopted a preferential treatment approach, rather than an asset transfer approach, as well as to a transparent policy environment.

Figure 3: Foreign direct investment flows, South Africa 1985–2012 (% of GDP) (24)

Empowerment programmes in other developing countries

Malaysia is an example of a country that has implemented a successful, robust and inclusive affirmative action programme to address past economic imbalances. The Malaysian Government implemented the New Economic Policy (NEP) from 1970 to 1981, aimed at eradicating poverty through expanding the economy and reducing the proportionate economic share of non-Malays. The objective was to increase the economic share of Malays from 2.4% of total wealth in 1970 to 30% in 1990; to reduce poverty; and to change employment patterns in urban areas to reflect the racial composition in the country.(25) Malaysia succeeded in attracting FDI regardless of the NEP because it had a relatively open and welcoming environment to FDI and maintained restrictions on purely financial flows. Furthermore, it offered incentives for export-oriented FDI and allowed for the establishment of special export processing zones where FDI was shielded from changes in government policies. Therefore, FDI as a proportion of GDP increased from 25% in 1975 to 29% in 1988, whilst by 1990 the economic share of Malays increased to 19.3% of total wealth and poverty levels fell to 17.1% of the ethnic Malay population.(26) This success was based on the flexibility of the Malaysian authorities in varying empowerment policies by allowing exceptions that suited the needs of foreign investors through incentives in export-oriented industries.(27) Malaysia’s experience holds a lot of lessons for African countries. First, asset–wealth transfer is not the only option in economic empowerment; preferential treatment for skills acquisition is another form. Second, transparency and well-defined policy fosters investor confidence. Finally, empowerment policies need to be flexible and accommodate some investor demands.

Concluding remarks

Economic empowerment policies are of concern to foreign investors if they are perceived to amount to appropriation and violation of private property rights. Our evidence suggests that the nature and speed at which empowerment programmes are implemented affects investor decisions. Thus, in South Africa and Botswana, investor confidence is fostered, presumably by economic empowerment programmes that are merit-based, sector-specific and allow for gradual implementation and exemptions in some cases. On the other hand, in Zimbabwe, past economic empowerment programmes – that is, the land reform programme – adopted a big bang approach to implementation without clarification of private property rights, whilst the IEEA is inflexible to certain investor demands with a one-size-fits-all approach that allows no exceptions. For economic empowerment programmes to succeed, policy implementation must be transparent for foreign investors to maintain or increase FDI flows into the host country.

Written by Gamuchirai Chiwunze (1)

NOTES:

(1) Gamuchirai Chiwunze is a Research Associate at CAI with interests and expertise in finance, macroeconomics, development economics and international trade. Contact Gamuchirai through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Finance & Economy unit ( finance.economy@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Nicky Berg.

(2) Marker, S., 2003, ‘Effects of colonization: Beyond intractability’, in Burgess, G. and Burgess, H. (eds.) Conflict information consortium essays. University of Colorado: Colorado.

(3) Lall, S. and Narula, R., 2004. Foreign direct investment and its role in economic development: Do we need a new agenda?, The European Journal of Development Research, 16(3), pp. 447–464.

(4) ‘The Citizen Economic Empowerment (CEE) Policy’, Government paper No. 1 of 2012, Government of Botswana, http://bbbee.typepad.com.

(5) ‘Black Economic Empowerment Act of 2003’, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), Government of South Africa, http://www.thedti.gov.za.

(6) ‘The Tenth National Development Plan 2010-16 (NDP 10)’, 2010, Botswana, https://extranet.sadc.int.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Black economic empowerment codes, 2004, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), South Africa, http://www.thedti.gov.za.

(9) ‘Black economic empowerment strategy’, 2004, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), South Africa, http://www.thedti.gov.za.

(10) ‘Background to Land Reform in Zimbabwe’, Embassy of Zimbabwe in Sweden, 2009, http://www.zimembassy.se.

(11) Ibid.

(12) ‘The Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act 14 of 2007’, Harare, Zimbabwe, http://www.sokwanele.com.

(13) ‘Monetary policy statement’, 2009, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Harare, http://www.rbz.co.zw.

(14) ‘Land reform and property rights in Zimbabwe’, Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, 2010, http://www.kubatana.net.

(15) ‘Policy Framework for Investment’, 2006, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Paris, France, www.oecd.org.

(16) United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, http://unctadstat.unctad.org.

(17) Graph compiled by author with data from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, http://unctadstat.unctad.org.

(18) Ibid.

(19) ‘The Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act 14 of 2007’, Harare, Zimbabwe, http://www.sokwanele.com.

(20) Ibid.

(21) Graph compiled by author with data from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, http://unctadstat.unctad.org .

(22) United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, http://unctadstat.unctad.org.

(23) ‘Investing in South Africa’ Deloitte South Africa, 2009, https://www.deloitte.com.

(24) Graph compiled by author with data from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, http://unctadstat.unctad.org.

(25) Menon, J., ‘Macroeconomic management amid ethnic diversity: Fifty years of Malaysian experience’, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Discussion Paper no. 102, 2008, http://www.adbi.org.

(26) Ibid.

(27) ‘Malaysia New Economic Policy 1970-1981’, 2008, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), http://www.adbi.org; Menon, J., ‘Macroeconomic management amid ethnic diversity: Fifty years of Malaysian experience’, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Discussion Paper no. 102, 2008, http://www.adbi.org.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here