Although corruption is a global phenomenon, it is more rampant and visible in many Sub-Saharan African countries than on any other continent. Corruption is one of the greatest challenges facing governments as it undermines and distorts public policy, leading to the misallocation of resources. This distorts market efficiencies, which affect private sector development and produce negative economic effects that hurt the poor. This CAI paper explores the nature of corruption and its cost implications on the development agenda of African countries.

What is corruption?

According to the World Bank, corruption refers to private wealth seeking behaviour by officials representing the state and the public authority, or the misuse of public goods by public officials for private gains; whilst in the private sector, corruption is associated with the payment of bribes to circumvent laid-down procedures.(2) Thus, corruption is prevalent in situations in which people in positions of trust have monopoly to use their discretion in executing their roles with less accountability to their superiors or stakeholders to the extent of abusing the monopoly for their private gains.(3) While corruption is a global problem, the impact is felt more in poor and underdeveloped countries, where corruption results in the diversion of public resources into private hands to the detriment of the poor.(4)

Corruption comes in different forms, namely, political corruption, bureaucratic corruption and economic corruption. Political corruption is that which results from government failure to implement, enforce and uphold the rule of law; bureaucratic corruption takes place in the form of bribery to public officials to distort due process in the public sector, such as acquiring drivers’ licences and other vital public documents and facilitating non-compliance with statutory obligations to the central government. Bureaucratic corruption undermines the capacity of governments to deliver services, as the poor, who do not have resources to participate in corrupt systems that rely on bribes, are effectively excluded from acquiring essential government services.(5) Lastly, economic corruption comes in the form of kickbacks, insider trading of information, and inflation of contracts in exchange for money and other benefits, whilst disregarding due process in economic transactions.(6)

According to Transparency International (TI), a Germany based anti-corruption organisation whose mission is to stop corruption and promote transparency, accountability and integrity across all sectors of society, Africa has the highest number of countries in the world ranked among the most corrupt.(7) Chika Ezeanya, a researcher in African Development Studies at the University of Rwanda, noted in July 2012 that the root cause of corruption in Africa can be traced to the legacy of colonial rule.(8) Indirect rule turned leadership into a corrupted enterprise which, instead of holding power in trust for the colonial authorities, enabled rulers to abuse authority to enrich themselves. Generally this was so in most African colonies because misfits in society who had no say in the running of community affairs were promoted as warrant chiefs by the colonial authorities, and these individuals in turn demanded money from the community in exchange for manipulating the bureaucratic process established by colonial masters.(9) To avoid being punished for failure to adhere to colonial requirements, people saw bribery as a first and last resort to be granted access to certain services and avoid being victimised by local administrators. However, there were instances in which legitimate local authorities were corrupted by colonial masters, colonial masters would not pay them their dues/wages for services offered, and would instruct them to extract their income from the people they served. The result was the establishment of a corrupt system in which self-enrichment became the order of the day.(10) However, human greed was present before colonialism, as corruption has been going on in Africa for centuries: traditional rulers sold their subjects and prisoners for their own interests during the slave trade by exchanging them for guns and exotic alcohol; thus, colonialism only exacerbated prevailing human greed.(11)

Following the attainment of political independence in many African countries in the early 1950s from mainly Britain, France and Portugal, Africa’s new governments inherited deeply corrupt institutions, laws and values from colonial governments. Instead of changing these colonial systems to get rid of corrupt tendencies, most newly established governments in the post-colonial era embraced and entrenched themselves in deeply-compromised governance systems by distributing jobs and government tenders along political lines and/or ethnicity. For instance, Nigeria’s first republic government after British colonisation under former president Abubakar Balewa was marked by widespread corruption, prompting a military coup d’état in 1966.(12) Such a system of self-entitlement also characterises many African countries currently, such as Cameroon, Mozambique, Nigeria and Zimbabwe.(13)

Anti-corruption initiatives in Africa

A number of legal frameworks exist regionally to fight corruption and these include the African Union (AU) Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. The convention was adopted in 2003 at the Second Ordinary Sessions of the assembly of the AU in Maputo, Mozambique and came into force in 2006. Currently, 34 member states have ratified the convention and are state parties.(14) The objectives of the framework are to promote and strengthen development within member states, and implement mechanisms to prevent, detect, punish and eradicate corruption in the public and private sectors by harmonising laws, policies and strategies. Parties through their national anti-corruption authorities are required to regularly submit reports on reforms to comply with provisions.(15) Although the provisions of the convention are mandatory, there is no provision that deals with penalties for failure to comply with prescribed measures; hence, some countries may not comply with certain provisions that they may deem to have complied with. Another problem is that national authorities established in most African countries lack adequate funding and skills to fully tackle and expose corruption in their countries.

However, despite anti-corruption and bribery legislation being in place, corruption has increased in countries like Cameroon, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe, with government efforts being insufficient to curb corruption.(16) For example, Nigeria has an Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and an Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) to fight corruption but, despite the presence of these statutory agencies, corrupt activities have continued. Meanwhile, in Zimbabwe, the Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) has become corrupt itself, making a mockery of the country’s anti-corruption efforts as those tasked with curbing corruption are taking the opportunity to enrich themselves by by-passing and knowingly violating the codes of conduct that regulate operations.(17) Another key reason why anti-corruption efforts have not been successful is that politicians and government officials seek personal gratification first at the expense of public interest.(18)

Cost and consequences of corruption to development

The cost of corruption can be divided into four main categories: political, economic, social, and environmental.(19) The economic effects of corruption depend on the type of corruption prevalent in each country and the quality of national governance. Countries with poor governance have been seen to experience high levels of corruption and this has caused a lot of harm to societies through negative effects on both the poor and private sector activities.(20)

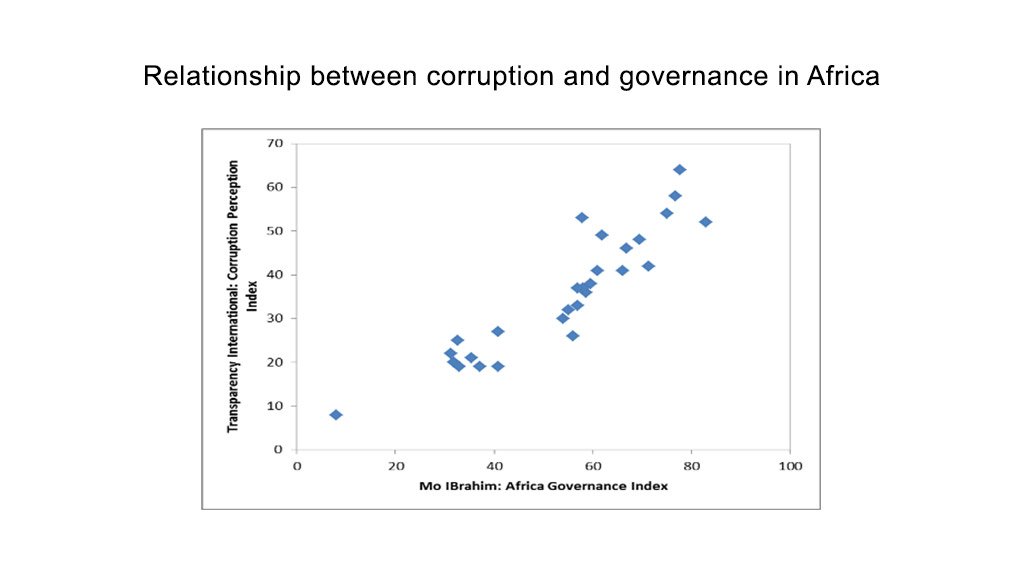

Figure 1: Relationship between corruption and governance in Africa (21)

The figure above seeks to show that there is a close relationship between a country’s governance performance and its level of corruption using data from TI’s 2013 Corruption Perception Index and the 2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance in 30 selected African countries. The Corruption Perception Index is a global reference for corruption and is based on the perception of a country’s citizens whilst the Ibrahim Index of African Governance provides an assessment of a country’s governance performance. The above results show a positive relationship between the TI Corruption Perception Index and the Ibrahim Index of African Governance in; that is, countries with poor governance scores also perform poorly in terms of corruption perception.(22)

Thus, whether poor households engage in corrupt activities or not, they suffer due to the inefficiencies that corruption produces in the economy. Corruption increases the cost of living for communities as it has the effect of adding to the daily cost of living and reduces people’s standard of living as both people and businesses have to pay bribes to government officers for survival.(23) For example, in Zimbabwe, private transport operators have pointed out police corruption in which officers demand bribes of US$ 5.00 or more at each road block. These bribes inhibit transport operators from earning sufficient wages as close to 40% of their revenue is lost to bribes and operators are forced to increase their fares, charging ordinary citizens a US$ 1.00 for distances which should be less than half that amount.(24) Thus, poor people without alternative transport choices are hurt the most as they must pay more to access the same level of services, which reduces their disposable incomes and, consequently, their standard of living.

The poor can be excluded from accessing public services as a result of corruption due to the effect of increasing government operating costs. Because public revenues are lost through corrupt activities, fewer resources are available for public services provision, and hence, the poor will bear the burden of corruption through higher tariffs for public services as governments attempt to finance and meet expected levels of service delivery. Since the poor have no alternatives to public services, they may also be excluded from basic services, like health care and education, if they cannot afford to pay bribes. The embezzlement or diversion of public funds further reduces government resources that would otherwise be available for development and poverty reduction.(25) Corrupt politicians and bureaucrats invest scarce public resources in projects to enrich themselves, rather than those that benefit communities, and prioritise high-profile projects, such as dams and football stadiums, over less spectacular but more urgent infrastructure projects, such as schools, hospitals and roads. For instance, in Uganda, more than US$ 51 million in grants meant for malaria and tuberculosis programmes from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), a Switzerland based organisation established in 2002 to provide health financing worldwide, were misappropriated by public officials in 2012, with funds disappearing into personal bank accounts of ministry of health employees and being channelled to non-governmental organisations that existed only on paper.(26) Programmes and beneficiaries entitled to benefit under the Global Fund Malaria funds were denied access to life-saving malaria medication and preventive mosquito nets, putting at risk the lives of millions of poor people who do not have alternative means to prevent malaria.(27)

Corruption has the effect of increasing the cost of doing business relative to less corrupt countries because bribes paid during the bargaining process add to transaction costs.(28) Moreover, bribery creates business uncertainty, while corrupt behaviour does not necessarily guarantee a company of business; other competing companies may be willing to offer higher bribes to swing business in their favour. In addition, corruption distorts market mechanisms, such as fair competition, which creates market inefficiencies and stifles growth and future business opportunities.(29) In most African countries, high levels of corruption have inhibited growth by acting as a disincentive to private investment as corruption increases uncertainties for business.(30)

The way forward

Corruption in Africa is very difficult to eradicate; because of this, it has given an impression that corruption has become entrenched in the mentality and perceptions of African people. However, for any anti-corruption reforms to be successful in reducing the level and impact of corruption, there is a need for strong political will from all stakeholders to purge corruption. Hence, there is need to bring on board all stakeholders affected by corruption, such as political leaders, civil society and citizens. This would ensure that there is ownership of anti-corruption initiatives among stakeholders, which is a minimum condition for their success.(31)

Reducing the monopoly of public officials to use their own discretion by instead introducing automated public sector processes could make it possible to curb corruption. Automation limits the authority of public sector officials and incentives to engage in corruption because officials have to follow a set of predefined procedures in executing their duties. This would allow decisions by government officials to be predictable and transparent, thereby preventing or deterring manipulation of government systems. Thus, any violation and breach of set guidelines and procedures by public officials would be noticeable and remedial actions could be taken.(32)

Governments may undertake institutional reforms to fight corruption, including incentives to promote ethical behaviour in public service. These incentives may include a performance-based incentive to bolster morale, professionalism and productivity and to link performance to compensation.(33) In addition, to improve accountability by people in positions of trust, there is a need to strengthen the transparency and oversight framework that governs their conduct, in particular by strengthening and adopting new codes of conduct for public officials and corporate governance frameworks for the private sector. However, because of poor governance and executive oversight in many African countries, even if these codes of conduct exist, they could be violated at will with no one held accountable. Thus such types of intervention will be successful only if countries have strong institutions and parliaments to hold the executive accountable.

Concluding remarks

Corruption has consequences far beyond the actual point at which a corrupt act has been committed. The wider implications for the general population, especially the poor, come as they are deprived of essential public services, while there are additional invisible costs for day-to-day activities incurred by the poor, businesses and the government. Although corruption in many African countries can be traced to colonialism, present day corruption has become deeply entrenched in the culture and norms in many societies; most people engage in corruption with impunity. Therefore, there is a need for a paradigm shift to tackle corruption effectively through limiting or completely removing the use of individual discretion in executing public duties to instead adopt routine procedures. In addition, there is a need to strengthen the institutional framework that governs the transparency and accountability of public officials so that public officials are taken to task over their actions.

Written by Gamuchirai Chiwunze (1)

NOTES:

(1) Gamuchirai Chiwunze is a Research Associate at CAI with interests and expertise in finance, macroeconomics, development economics and international trade. Contact Gamuchirai through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Finance & Economy unit ( finance.economy@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Nicky Berg. Research Manager: Ingi Salgado.

(2) ‘Helping countries combat corruption and the role of the World Bank’, World Bank, http://www1.worldbank.org.

(3) Amundsen, I., ‘Political corruption: An introduction to the issues’, Chr. Michelsen Institute Development Studies and Human Rights working paper 1999:7, 1999, www.cmi.no.

(4) ‘Combating corruption, improving governance in Africa’, Regional Anti-Corruption Programme for Africa (2011-2016), Economic Commission for Africa and African Union Advisory Board on Corruption, http://www.auanticorruption.org.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) ‘2010 Corruption Perceptions Index’, Transparency International, 2010, http://www.transparency.org.

(8) Ezeanya, C., ‘Origin of corruption in Africa and the way forward’, Chika for Africa Blog, 21 August 2012, http://chikaforafrica.com.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ibid.

(11) ‘Corruption in Africa’, Africa on the Blog, 13 July 2011, http://www.africaontheblog.com.

(12) Ogbeidi, M., 2012. Political leadership and corruption in Nigeria since 1960: A socio-economic analysis. Journal of Nigeria Studies, 1(2), pp. 2-25, http://www.unh.edu.

(13) ‘Africans inherited corruption’, The Sunday Independent, 19 March 2012, http://www.iol.co.za.

(14) ‘Status of ratification of the Convention on Corruption’, African Union Advisory Board on Corruption, 2012, http://www.auanticorruption.org.

(15) ‘African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption’, African Union, July 2003, http://www.agora-parl.org.

(16) Richmond, S. and Alpin, C., ‘Governments falter in fight to curb corruption’, Afro Barometer Policy Brief No 4, 13 November 2013, http://www.afrobarometer.org.

(17) Maodza, T., ‘Pay scandal rocks anti-graft body’, The Herald, 27 February 2014, http://www.herald.co.zw.

(18) Mwenda, A. M., ‘Best way to fight corruption’, The Independent, 23 November 2012, http://www.independent.co.ug.

(19) ‘2010 Corruption Perceptions Index report’, Transparency International, 2010, http://www.transparency.org.

(20) ‘The rationale for fighting corruption’, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) policy brief, 2014, www.oecd.org.

(21) Created by the author with data from: ‘2013 Corruption Perception Index’, Transparency International, 2013, http://www.transparency.org and ‘The Ibrahim Index of African Governance’, Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2013, http://www.moibrahimfoundation.org.

(22) Ibid.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Mudhokwani, S., ‘Traffic cops’ rot affecting citizens’, Centre for Public Accountability, Zimbabwe, 21 May 2012, http://www.cpazimbabwe.org.zw.

(25) ‘Transparency and private investment in Africa’, Transparency International, 9 May 2014.

(26) ‘Uganda shaken by fund scandal’, Washington Times, 15 June 2006, http://www.washingtontimes.com.

(27) ‘Uganda: Concern over allegations of misuse of Global Fund money’, Irin News, 1 October 2012, http://www.irinnews.org.

(28) ‘The rationale for fighting corruption’, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) policy brief, 2014, www.oecd.org.

(29) ‘Transparency and private investment in Africa’, Transparency International, 9 May 2014.

(30) Emery, J., ‘Governance, transparency and private investment In Africa’, Paper presented at the OECD-Africa Investment Roundtable, Johannesburg, South Africa, November 2003, http://www.oecd.org.

(31) Salihu, G., ‘Fighting corruption: Effective examples from surprising places’, Politics in Spires, 26 November 2012, http://politicsinspires.org.

(32) Hors, I., ‘Fighting corruption in the developing countries’, Development Centre, OECD Observer No 220, April 2000,http://www.oecdobserver.org.

(33) ‘A handbook on fighting corruption’, Centre for Democracy and Governance, US Agency for International Development, February 1999, http://www.dochas.ie.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here