On 23 November 2013, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) nineteenth annual Conference of the Parties (COP 19) closed after almost two weeks of debate and controversy in Warsaw, Poland. Although the need for international collaboration and decisive action was clear, the conference was instead characterised by an “unwilling(ness) to take concrete actions,”(2) North-South divide,(3) and lack of developed country leadership,(4) which ultimately culminated in “little reason for high hopes” and modest results largely considered “too little, too late.”(5) At a time when determined strides into the future are needed in order to avoid unequivocal climate disaster, baby steps, at best, resulted from the COP 19. At present, the capacity of vulnerable developing countries, and particularly the ability of African countries to prepare themselves for the adverse effects of rising global temperatures is constrained by developed-country support that falls extremely short of equitable responsibility, pledged commitments and evidence-based necessity.

Looking past the COP 19 and toward the future, this CAI paper explores international climate change responses and climate finance mechanisms as they relate to the global emissions gap and, specifically, Africa’s adaptation gap. The main prospects and challenges posed by the recently concluded COP 19 in Warsaw are summarised, as is the latest evidence on global emissions capping efforts and climate finance. In addition, the climate-related threats to the continent are explored and Africa’s ability to respond to these threats is analysed. Finally, the opportunities and trials posed to Africa looking forward to the uncertain future are discussed.

COP 19: A lot of talking and little walking

Every year since 1995, the COP convenes in a world city to discuss an increasingly pressing agenda: to assess international progress and responses to climate change. This meeting is meant to foster collaboration between the 195 parties, or countries, and provides a critical platform for the world’s countries to negotiate equitable and effective international agreements that will decrease global emissions and mitigate climate threats. Recently, over 8,300 delegates and participants congregated in Warsaw, Poland, where COP 19 was hosted from 11-23 November 2013.(6) More contentious issues on the agenda, such as loss and damage and climate finance mechanisms, were intensified by an undertone of trepidation as parties prepare for a meeting in New York in September 2014, where countries will be required to provide evidence of the actions taken to decrease their emissions, shortly followed by a 2015 conference in Paris that marks the deadline for ratifying a binding agreement to reach specific emissions cut targets to come into effect by 2020.

The weeks preceding the COP 19 in Warsaw were saturated with urgency and hopeful anticipation as calls to action rang from the media, the public, scientists, civil society organisations, and vulnerable countries alike. In the run up to the conference, Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report, which presented the scientific evidence proving that global warming is “unprecedented” and “unequivocal,” and that the main driver of global temperature increase is almost certainly human influence.(7) Adding to this, Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines shortly before the Warsaw meeting convened, claiming over 2,000 lives, displacing more than half a million people, and affecting the lives of over 11 million individuals,(8) exemplifying the disasters that are likely to occur more frequently and more intensely as global temperatures increase.

Yet “in striking contrast to reality on the ground and in the atmosphere, a sense of resolve was noticeably absent” at Warsaw,(9) and most of the outcomes of the COP 19 seemed to relay little urgency. A refusal of developed countries to entertain discussions regarding compensation for the loss and damage unavoidably suffered by developing countries, combined with the failure of pledges toward the US$ 100 billion in climate finance promised by 2020, and general “lack of progress,” 800 representatives of environmental groups walked out of discussions on 21 November,(10) a day after the G-77 and China bloc of 132 countries left conference negotiations when developed nations refused to discuss compensation until after 2015.(11) Developed countries seemed primarily concerned with insisting that negotiations proceed without consideration of differentiation between themselves and developing countries,(12) suggesting that their fear of mounting climate-related financial commitments negate the need for equity.

These disagreements brought the conference discussions to a standstill as a divide between developed and developing nation interests became increasingly evident. Eventually, 27 hours after the COP 19 was meant to close, the parties agreed to draft a Warsaw international mechanism for loss and damage. This agreement calls for support to countries that are “particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change” to protect themselves against the unavoidable costs that “result from slow onset or extreme weather events that cannot be prevented by even the most ambitious mitigation action.”(13) At this point, however, the Warsaw international mechanism only “requests” financial assistance and since its mandates are not set to be reviewed until COP 22 in 2016,(14) it is difficult to know whether this mechanism will be able to serve as an effective tool for vulnerable countries in the interim. Parties also agreed to amend countries’ “commitments” to cutting global emissions to “contributions,” a further desperate effort to differentiate between the differing responsibilities of developed and developing nations.(15) In reality, however, this does little to delineate the sort of ‘contributions’ countries should be expected to make as post-2020 emissions cuts draw nearer.

As yet, only four countries have ratified the Doha Amendment, and until a further 140 countries ratify it, parties are not legally bound to the quantified emissions limitation or reduction commitments (QELRCs) delineated in the agreement.(16) Extremely little progress was made in negotiating the treaty expected to be introduced in Lima, Peruin 2014, to replace the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. Perhaps most worrying is that the existing discussion surrounding this approaching treaty suggests that countries will determine the emissions cuts they will be held accountable for as well as the pathways to achieving them, regardless of whether such cuts are representative of a party’s share of global emissions or whether the cuts, collectively, are adequate to keep average global temperature rise to under 2 degrees Celsius (˚C) from pre-industrial levels.(17) Although parties re-established the need to tighten and strengthen country-based efforts to decrease global emissions,(18) there was little tangible discussion of what this means in reality throughout the coming years. Some countries, such as Japan, announced future emissions cuts that effectively result in emissions higher than their 1990 baseline levels.(19) Over US$ 100 million was pledged to climate funds,(20) and while these pledges should be taken seriously and should also be appreciated, these pledges are a long way away from the commitment of US$ 100 billion funded annually by 2020.

All in all, the COP 19 closed on 23 November 2013 having covered little of the ground that needs to be travelled before COP 20 in Peru commences in 2014 and a decisive Paris meeting follows in 2015. Given the overall disappointing results of the conference at a time when collective, decisive action is critical, it is not surprising that a sense of desperation and separation is being expressed among climate justice activists and vulnerable countries that cannot adequately protect themselves (from a threat they largely did not create) without international support and cooperation. The following section explores the evidence that developing countries’ frustrations over lack of progress, little support, and lack of care towards equality are founded on.

The evidence: The emissions gap and climate finance shortfalls

Without question, the latest scientific evidence in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report relays the critical nature of the changing climate and the necessity of immediate action. Since the mid-nineteenth century, sea levels have been rising at paces faster than the average of the past 2,000 years, the concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are the highest that they have been in at least 800,000 years, and carbon dioxide levels have nearly doubled since the pre-industrial period.(21) Furthermore, better quality and quantity of data have confirmed that “human influence on the climate system is clear” and is “extremely likely to be the “predominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-twentieth century.”(22)

The past has passed, and if measures are not taken now to keep average global temperature rise to under 2°C, then the future is uncertain. Yet, despite the pressing need for serious action, the analysis presented in the recently published 2013 Emissions Gap Report suggests that the progress that has been made to date is not enough to keep under the 2°C mark.(23) In fact, only five parties (namely Australia, China, the European Union, India and the Russian Federation) are in line to stay under their pledged 2020 emissions caps.(24) Most worrying of all is that even if every party managed to fully honour their emissions pledges, the emissions gap, or the extent to which global emissions will be too high to come under the 2°C mark, will be 8-12 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2020.(25) Given the lack of action and political will, such as that displayed at the COP 19, the chances of being in the upper range of that zone are more and more likely. Considering present efforts, there is a 40% chance that the global temperature rise will reach 3.5-4°C by the turn of the century.(26) The likely consequences of a 2°C temperature rise are already hefty; the social, environmental, economic, and health costs of a 3-4°C increase would be devastating - especially so for vulnerable regions and developing countries.

Developing countries’ ability to adapt to such consequences of climate change is limited by their geography and resources. Without international support to these vulnerable countries from wealthier countries, which are almost single-handedly responsible for the emissions causing current climate effects, developing countries will remain extremely exposed to climate-related disaster. This is why international funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), have been set up to provide assistance to these countries in their efforts to adapt to and mitigate climate change. The GCF was established at the 2010 COP 16 in Cancun, accompanied by a commitment to increase funds to US$ 100 billion per year by 2020.(27)

As yet, the promising opportunity of the GCF has been extremely limited as this funding mechanism is not yet even fully functional. The fund’s biggest pledge for US$ 40 million came from South Korea, a Non-Annex 1 country with no obligation to contribute to the GCF.(28) The US$ 9 million officially in the fund, allocated to cover administrative costs, does not even cover the 2014 budget for administration.(29) The slow funding and stalled progress is partly due to a lack of clarity on the Fund’s financing mechanisms, the components of which are continually disagreed upon between developed and developing countries. How the funds will be allocated among countries and balanced between adaptation/mitigation efforts are still undecided. (30) COP 19 did little, if anything at all, to break ground on these stumbling blocks, and so the GCF remains an untapped resource for countries that currently and direly need assistance.

Beyond a faltering GCF, climate finance on the whole is nowhere near adequate. The Overseas Development Institute reported that prior to COP 19, pledges to multilateral climate funds in 2013 were down 71% from 2012.(31) Another sobering exemplification of this that the funds made available in response to floods in Germany in 2013 were four times greater than the total sum (from 2003 to present) available to assist developing countries in their efforts to adapt to climate change.(32) Although US$ 72.5 million in climate adaptation funding was pledged by European parties at COP 19, the gap between this sum and the US$ 100 billion, over ten times that much pledged to be available annually by the end of the decade, is undeniable.

This disparity between what is needed for developing countries to protect their populations from the effects of climate change and what is available to help them adapt is what fuels frustration over ‘climate injustice’. It is the countries who are least equipped to deal with climate change and who have least contributed to temperature rises that are the most exposed to the effects thereof. Specifically, the African continent is responsible for fewer global emissions than any other continent; paradoxically, it is the continent that is expected to suffer the greatest consequences.(33) The following section explores why.

Africa’s adaptation gap

Even if every country honoured its 2020 emissions targets, African governments would still have a tremendous challenge in meeting the continent’s adaptation needs. Because it seems less and less likely that pledges will be met and more likely that the 2°C mark will be breached, Africa, as a whole, is left in a very risky, exposed and dangerous position. Regardless of the global emissions cuts that may be made in the coming years, adaptation costs for the continent are expected to reach US$ 7-15 billion per annum by 2020, and rise sharply thereafter as intensity and frequency of climate-related disasters also increase.(34)

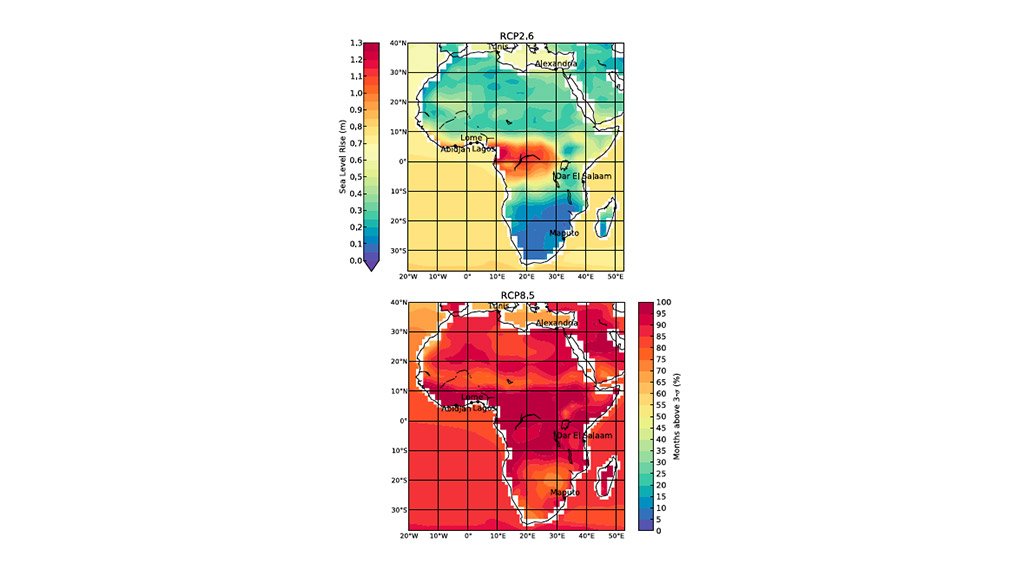

The social, environmental, and public health costs to Africa associated with a 2°C temperature rise - or a 3.5-4°C temperature rise, as is becoming more and more likely - is stark. Already, if the average temperature rises by 1.2-1.9°C before 2050 as anticipated, incidence of malnourishment in Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to increase from present levels by up to 90%.(35) Once global temperature rise averages above 3°C (within the century), all of the areas on the continent where maize, millet and sorghum are currently cultivated will no longer be able to sufficiently nourish crop production,(36) critically limiting agricultural productivity and consequently fostering further malnourishment. Consider the scenario in a world where temperature rises peak above 4°C rather than under 2°C: summer temperatures in Sub-Saharan Africa will climb 4-6°C above present levels instead of 1-2°C; the sea level along the coast will rise by up to one metre at the turn of the century as opposed to 60-80 centimetres (as exemplified in Figure 1); and aridity changes, which make agriculture less and less viable, will be more than double the changes associated with keeping global temperature change under 2°C.(37)

Figure 1: Projections for sea-level rise above present-day levels (ocean - top legend) and

warming compared to present-day extremes (land - bottom legend) for 2100.

A 2°C warming scenario (RCP2.6) is shown at the top;

a 4°C warming scenario (RSP8.5) is shown at the bottom.

Source: PIK (Schellnhubur et al., 2013) (38)

The difference in the financial burden associated with Africa’s adaptation needs in a 2°C rise and a 3.5-4°C rise is monumental. In the former scenario, Africa’s adaptation costs are predicted to reach US$ 35 billion by 2040 and US$ 200 billion by 2070; in the latter instance, costs are projected at US$ 45-50 billion by 2050 and US$ 350 billion by 2070.(39) Without action now that prevents temperature rise from soaring to the 3.5-4°C range, loss and damage to the African continent could cost 7% of annual gross domestic product by the end of the century.(40) Without assistance, there is no way that African countries can be expected to cope with this, and millions upon millions of lives will be directly and indirectly affected.

In addition to immediate innovation, creativity, and collaboration across the continent’s governments, the lives and livelihoods of Africans rely heavily on whether developed countries will assume their respective responsibility for the consequences of anthropogenically-driven temperature rises. For Africa to be able to protect its people from climate change threats, the amount of adaptation finances available needs to rise by 10-20% each year from now until the 2020s.(41) Thereafter, until the 2050s, assuming pre-2020 funding is sufficient, climate finance will need to continue to increase 7% annually in order to allow African countries to adapt to the inevitable adverse effects.(42) This means that the US$ 100 billion annually promised by developed countries before 2020 needs to move from promise to reality, and the funds then need to be allocated to vulnerable countries for adaptation or mitigation purposes, and this must happen now, before the costs become too great to bear.

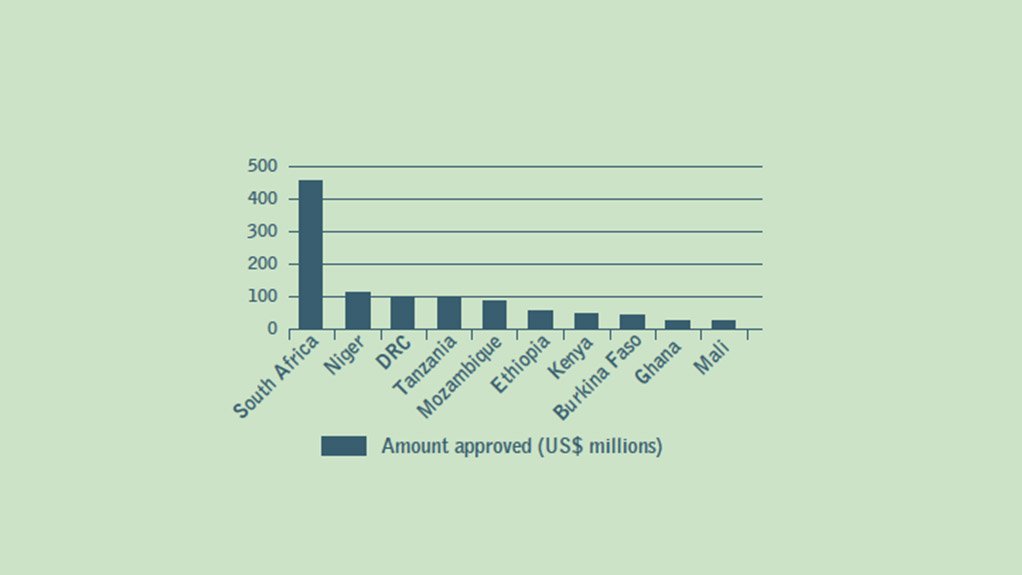

Unfortunately, the amount of available adaptation funding for Sub-Saharan Africa to date is pathetic in comparison to the need. Since 2003, only US$ 1.73 billion in total has been approved for various climate projects, a far cry from the US$ 18 billion that is required annually, and even further from the US$ 100 billion annually pledged by 2020.(43) Of this funding, 40% is allocated specifically for mitigation purposes, which, although necessary to adequately protect countries from climate threats, have been deemed less pressing than adaptation - given Sub-Saharan Africa’s extreme vulnerability.(44) Less than half of these funds approved for adaptation projects in the region have been received,(45) and as Figure 2 shows, most of this has only gone to a few countries, and over one quarter of it to South Africa alone.(46)

Figure 2: Top recipient countries of African climate finance funding (US$ millions) (47)

The case is clear: without access to climate finance, Africa cannot close its adaptation gap. Even if temperature rise is kept under 2°C and all current pledged climate funding was first realised and then made available to the African continent alone, it would not be enough to meet adaptation costs.(48) Because of this, many experts warn that a global temperature rise greater than 2°C would result in adaptation costs on the continent that would simply be “unmanageable.”(49) So it is that the people of Africa, an entire continent whose current contribution to global emissions weighs in at a measly 4%,(50) will lose their lives, health and livelihoods unless the world’s leaders collaborate to avoid such injustice and inequality. Unfortunately, at a time when needed most urgently, neither North-South collaboration nor global climate leadership were prominent themes of the COP 19.

Looking to the future: What now?

The COP 19 fell remarkably short of its potential; the consequences to vulnerable countries which must act now but do not have the means to do so could be devastating. Yet at a time when action is needed more than ever before and collaboration and innovation are critical, hope and determination is an absolute must. On one hand, the results of the COP 19 resemble waning leadership, domestically-centred interests, and disregard for historical responsibility; on the other hand, the successes that did result from the conference exemplify what can be achieved when developing countries take a stand together and demand just action. Although developed-developing country partnership would be optimal, the potency and potential of South-South collaboration has proved that it has the ability to take decisive steps to prepare for the future, even if wealthier comrades hesitate or procrastinate. Here, in South-South collaboration, lies immense opportunity.

It is also important for developing countries and the continent of Africa to avoid following in the footsteps of their development predecessors. Now that the evidence reveals the consequences of the industrial period, and since the technology is available to develop more sustainably, developing countries should take to heart the wisdom from past and present intended and unintended oversights of developed countries and be sure to avoid the same. If we hope to live in a viable world, then it is not enough for developing countries to excuse their lack of action because developed countries are also slow to act. Lead by example. After all, although the per capita emissions of developing countries are lower than their wealthier counterparts, in absolute levels, developing countries account for 60% of global emissions,(51) and their share is likely to continue to increase with further development. Therefore developing countries, too, must responsibly pave the way toward a sustainable future.

There is cause for hope. The latest evidence suggests enough technology and tools to close the global emissions gap and stay under the 2°C target by 2020 is available.(52) It is time that is running out, not creativity, innovation, and possibility, and it is political will, global collaboration, and decisive action that is inadequate. If we stand together and act immediately, then Africa, and the world, can close the adaptation and emissions gaps and set an unprecedented example of equitable, sustainable change.

Written by Rachel Rose Jackson (1)

NOTES:

(1) Rachel Rose Jackson is a Research Associate with CAI and a healthcare professional whose work focuses on how systems can develop sustainably in ways that mitigate climate change consequences to health and the environment while promoting social equity. Contact Rachel through Consultancy Africa Intelligence’s Enviro Africa unit (enviro.africa@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Liezl Stretton.

(2) Jolly, D., ‘Deals at climate meeting advance global effort’, New York Times, 23 November 2013, http://www.nytimes.com.

(3) Mwendwa, A., ‘Climate change: Rich nations say developing countries are equally responsible’, Urban Gateway, 21 November 2013, http://www.urbangateway.org; Twidale, S. and Chestney, N., ‘Green groups quit Warsaw climate talks over lack of progress’, Reuters, 21 November 2013, http://www.reuters.com; ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca; Vidal, J., ‘Poor countries walk out of UN climate talks as compensation rumbles on’, The Guardian, 20 November 2013,

http://www.theguardian.com.

(4) ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) ‘Climate change 2013: The physical science basis, Working Group I contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for policymakers’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013, http://www.climatechange2013.org.

(8) ‘Typhoon Haiyan: Aid in numbers’, BBC, 14 November 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk.

(9) ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca.

(10) Twidale, S. and Chestney, N., ‘Green groups quit Warsaw climate talks over lack of progress’, Reuters, 21 November 2013, http://www.reuters.com.

(11) Vidal, J., ‘Poor countries walk out of UN climate talks as compensation rumbles on’, The Guardian, 20 November 2013, http://www.theguardian.com.

(12) Mwendwa, A., ‘Climate change: Rich nations say developing countries are equally responsible’, Urban Gateway, 21 November 2013, http://www.urbangateway.org.

(13) ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca.

(14) Ibid.

(15) McGrath, M., ‘Last minute deal saves fractious U.N. climate talks’, BBC, 23 November 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk.

(16) ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca.

(17) Ibid.

(18) ‘UN Climate Change Conference in Warsaw keeps governments on a track towards 2015 climate agreement’, United Nations Environment Programme, 25 November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(19) ‘Summary of the Warsaw Climate Change Conference: 11-23 November 2013’, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 26 November 2013, http://www.iisd.ca.

(20) Ibid.

(21) ‘Climate change 2013: The physical science basis, Working Group I contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for policymakers’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013, http://www.climatechange2013.org.

(22) Ibid.

(23) ‘The emissions gap report 2013: A UNEP synthesis report’, United Nations Environment Programme, November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(24) Ibid.

(25) Ibid.

(26) ‘Africa climate change adaptation costs could soar to USD $350 billion annually by 2070 if warming hits 3.5-4°C UN Report’, United Nations Environment Programme, 19 November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(27) Schalatek, L., Stiftung, H.B. and Nahkooda, S., ‘The Green Climate Fund’, Overseas Development Institute, November 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(28) ‘Ten things to know about climate finance in 2013’, Overseas Development Institute, 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(29) Schalatek, L., Stiftung, H.B. and Nahkooda, S., ‘The Green Climate Fund’, Overseas Development Institute, November 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(30) Ibid.

(31) ‘Ten things to know about climate finance in 2013’, Overseas Development Institute, 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(32) Ibid.

(33) Schaeffer, M., et al., ‘Africa’s adaptation gap technical report: Climate-change impacts, adaptation challenges, and costs for Africa’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(34) ‘Africa climate change adaptation costs could soar to USD $350 billion annually by 2070 if warming hits 3.5-4°C UN Report’, United Nations Environment Programme, 19 November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(35) Schaeffer, M., et al., ‘Africa’s adaptation gap technical report: Climate-change impacts, adaptation challenges, and costs for Africa’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(36) Ibid.

(37) Ibid.

(38) Ibid.

(39) Ibid.

(40) ‘Africa climate change adaptation costs could soar to USD $350 billion annually by 2070 if warming hits 3.5-4°C UN Report’, United Nations Environment Programme, 19 November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(41) Schaeffer, M., et al., ‘Africa’s adaptation gap technical report: Climate-change impacts, adaptation challenges, and costs for Africa’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(42) Ibid.

(43) Nakhooda, S., Barnard, S. and Caravani, A., ‘Climate finance regional briefing: Sub-Saharan Africa’, Overseas Development Institute, November 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(44) Ibid.

(45) Ibid.

(46) Ibid.

(47) Ibid.

(48) Schaeffer, M., et al., ‘Africa’s adaptation gap technical report: Climate-change impacts, adaptation challenges, and costs for Africa’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(49) Ibid.

(50) Nakhooda, S., Barnard, S. and Caravani, A., ‘Climate finance regional briefing: Sub-Saharan Africa’, Overseas Development Institute, November 2013, http://www.odi.org.uk.

(51) ‘The emissions gap report 2013: A UNEP synthesis report’, United Nations Environment Programme, November 2013, http://www.unep.org.

(52) Ibid.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here