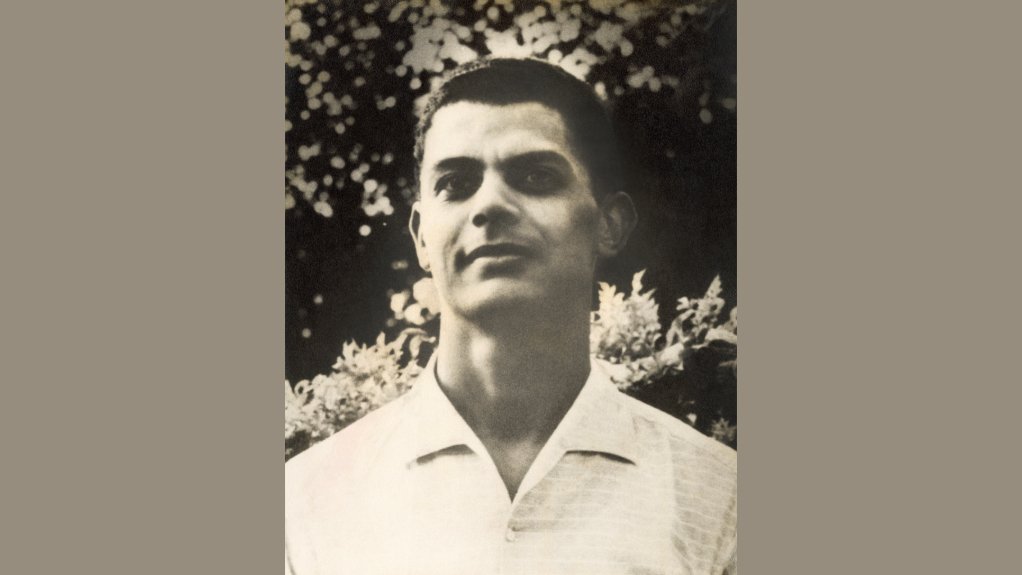

Basil February was born in Cape Town in 1943 and matriculated from Trafalgar High School in 1960 with five distinctions.

Although his desire was to study law at the University of Cape Town (UCT), his application was refused by the then Deputy Minister of Education, Arts and Culture, BJ Voster. He subsequently enrolled at UCT’s medical school, but being more absorbed in political struggle, dropped out the following year. February joined the South African Coloured People’s Congress (SACPO) in 1963. At a time when public meetings were banned, February and his comrade James April painted political graffiti to communicate their message. These activities soon landed him in trouble with the law. In 1964, February joined Umkhonto we Sizwe. Fearing that knowledge of his plans to skip the country might put family and friends in great danger, he disappeared without bidding his family and friends goodbye. They would never see him alive again. He secretly left Cape Town and made his way to Botswana and later underwent training in guerrilla warfare in other African countries and in Czechoslovakia. He was a member of MK’s Luthuli detachment and died in combat in 1967.

(see: Basil February (1943 – 1968)

He was a gifted intellectual and writer and contributed many articles to Dawn, the Umkhonto we Sizwe journal.

In 2003 he received the National Honours (the Mendi decoration in Gold- posthumously)

February’s remains were buried for over five decades in an unmarked grave in Bulawayo. In September these remains were finally brought home through The Repatriation and Reburial Project for Liberation Stalwarts which is a collaborative effort involving several government departments and entities.

The entities involved include the Presidency, the National Department of Sport, Arts and Culture, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, the Department of Home Affairs, the National Prosecuting Authority’s Missing Persons Task Team, the Department of Defence and Military Veterans, as well as various provincial departments. (see: Freedom fighter Basil February’s remains finally handed over to his family | SAnews)

The project also works closely with local communities, historical experts and governments at various levels to ensure a smooth and dignified process.

Basil’s brother, Terence travelled to Bulawayo where the remains were found. In a country as complex as ours and with much which remains untethered, the process has been an example of ensuring we never forget while at the same time providing a catharsis, done at every turn, with sensitivity and care by those within and outside of the South African government and related agencies.

Basil’s remains were buried in his birth town of Somerset West this week. Below is the eulogy delivered by Judith February, whose father and Basil were cousins. It represents the closing of the circle for the family but also a moment which provided pause for reflection on our democratic project.

Below is an edited version of Judith February’s eulogy:

‘Many have spoken about Basil’s short life and his commitment to liberating our country at a time when that seemed almost impossible.

It reminds me of the words emblazoned very plainly on a piece of marble forming part of the Korean War memorial in a quiet corner of the National Mall in Washington DC in the United States – ‘Freedom is not free’.

As for us here in South Africa, those words - Freedom is not free - ring true on many days and particularly this day- a poignant reminder of a citizen returned.

Speaking at the Freedom Park ceremony to honour those like Basil whose remains had been repatriated, President Ramaphosa said, ‘Through the act of repatriation, we reinstate their citizenship. We return them to the land of their birth. We restore them to their families and their people.’

Basil February left the country of his birth, a pariah and has now made another ‘freedom route’ back to South Africa, recognised as a citizen.

The South Africa Basil left was a country at war with itself. Basil, this child born in Somerset West, who experienced an itinerant childhood from there to Wolesley and then the West Coast.

In a sense it set the scene for a short life, anchored to the country of his birth in ideals and yet who died in a foreign land, at that time also not free.

What was the political context in which Basil found himself as he fled the country, with his friend James April- who is present today and whom we must also honour, as a friend and stalwart of Basil’s: their stories are intrinsically linked.

In 1960 after the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC was banned and in 1961 white people voted in a referendum for South Africa to become a white-ruled Republic. It was a desperate time as described by Basil’s cousin and my uncle, Vernon February, who in a different way contributed to the struggle for freedom, in a beautiful article written in 1990 in Die Suid Afrikaan magazine:

‘In 1964 het daar baie dinge gebeur in die land. Neville Alexander het later tronk toe gegaan, Leftwich, Alan Brooks en Stephanie Kemp was voorblad-nuus. En Mandela en sy mede-stryders is ná die Rivonia-verhoor gevonnis..

Young activists were increasingly attempting to leave South Africa via ‘freedom routes.’ The political historian Greg Houston has told the history of Basil, James and their comrades who took up arms to free South Africa.

Botswana was one of the first exits or so-called ‘freedom routes’ out of South Africa. And so, April and Basil’s journey in exile went from Botswana to Zambia to Tanzania to Czechoslovakia, back to Tanzania and back to Zambia. Basil and April spent 11 months (from 1964 to 1965) undergoing military training in Czechoslovakia. James April has described the education they received then, both politically and as soldiers. But also describes with wonder how cosmopolitan the whole experience was. They were joined by students from around the world, from countries in Africa and Asia, fighting for freedom from colonialism.

In 1966, Basil, James, and soldiers collectively known as the Luthuli Detachment, for the ANC’s president at the time, were to fight their way from Zambia across the Zambezi, into Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and then to open a corridor into South Africa for personnel and supplies. This march became known as the Wankie campaign. Basil was to die in combat 16 days later.

The return of Basil’s remains prompts reflection on South Africa's democratic journey, questioning whether it still embodies its constitutional ideals of equality, human rights, non-racialism, unity amidst diversity and open, accountable and responsive government?

Despite immense progress, we know that we remain very far from the ideals of a truly free South Africa. In a country with a staggering 33.5% unemployment rate and ever-deepening levels of inequality. Each day we are bombarded with news of a society which in many ways has lost its moorings, an ANC so bereft of an ethical compass that it lost the most recent elections.

We also live with the shadow of the 2021 insurrection, its instigators, mostly not held to account and a country whose Parliament has as MPs some of those who have been involved in state capture or who have broken their constitutional oaths of office. Some in the People’s house are populists, who eschew complexity, who don the workers’ overalls as fancy dress, who wear military camouflage as the faux revolutionaries they have become now, spewing forth racial tropes only seeking to divide. These all threaten our hard-won democracy.

Against this socio-political backdrop, it is tempting to want to ask and answer the question –‘ what would Basil have done in today’s South Africa?’ What would he have thought of our democracy? Where would he have been? In government? A lawyer? A writer- he had written for Dawn and Mayibuye, after all? Comrade Rodgers once described Basil as ‘instinctively brave.’ and said, ‘There is no doubt that this comrade is a true hero, whose name must never be forgotten in our songs and poems. His bones were definitely going to be taken to a' free and independent South Africa. He was young. ‘If he was alive to this day, he would be one of our greatest leaders.’

But, we should be careful not to turn Basil into a stick figure, a kind of ideal citizen.

Here I am reminded of what the American political scientist Adolph Reed Jr. once wrote about how he wanted to debate the legacy of Malcolm X, who was murdered two years before Basil in the equally volatile, repressive and racist circumstances of the US. Malcolm X, was, Reed argued, ‘

“… he was just like the rest of us—a regular person saddled with imperfect knowledge, human frailties, and conflicting imperatives, but nonetheless trying to make sense of his very specific history, trying unsuccessfully to transcend it, and struggling to push it in a humane direction.”

In a sense it is therefore better to ask, ‘In his short life what were the things which animated Basil, which caused him to give his life for a cause far greater than himself?

When Basil February died a discussion paper he had delivered, entitled, ‘The social basis of National Party power’ was found amongst his belongings. It was one of a series of lectures he delivered to his UmKhonto we Sizwe unit before he died in 1967.

The article is interesting for its content. In it, Basil discusses the nature and extent of the National Party’s support base in the context of the 1961 referendum. A key vehicle for its power was of course the state’s protection of and provision for the white workers.

The essence of Basil’s class analysis was a focus on the protection of "poor whites" and white workers in South Africa, including their wages and job reservation. Most importantly, Basil advocates for employment for all South Africans especially the black majority.

What we know from this is that Basil was concerned then about structural inequality. Even at such a young age his insights in the economics of apartheid and what kept it alive. Any system needs people to keep it alive.

Basil is often celebrated as the ‘first ‘coloured’ MK soldier to lose his life in the struggle.’ We are reminded that at the time coloureds could be members of MK, but not of the ANC. That only happened three years later at a landmark conference in Morogoro, Tanzania, where the ANC also had to deal with other problems: its exiled leadership seen as distant, old, out of touch, struggling to build international solidarity for the struggle back home. One could argue that people like Basil and James here with us, or Chris Hani, represented another vision for the ANC and for the struggle: as accountable, multiracial, and principled. As we know and James April reminds us, that in the years planning the 1969 conference, Oliver Tambo, who emerged as ANC leader, “had intended promoting young cadres to senior and executive ANC bodies, like Basil. Basil’s death had robbed Tambo of one of his favourite young cadres,’ in James’ words.

I want to mention one other aspect of Basil’s life; he was unmistakenly Afrikaans. We know this from his cousin and my uncle, Vernon. In 1989, Vernon was attending the gathering of Afrikaans writers and academics who met with the 20 members of the ANC at Victoria Falls. Vernon was then a professor at Leiden university in the Netherlands and part of the ANC delegation. Ironically this meeting was facilitated by Idasa, the organisation I would end up working for 11 years later. Vernon remembers that Marius Schoon, a white ANC member whose wife and daughter had been killed by a parcel bomb had taken the mic. Vernon wrote, ‘Marius Schoon het in sy kraakrype stem gesê, terwyl hy die lessenaar vasgegryp het: "Laat ons nie vergeet dat twee van die grootste helde van die ANC albei Afrikaans as hulle moedertaal gehad het nie. Die een was Bram Fischer, die ander man was Basil February."

In a country which holds an often tenuous place for Afrikaans given our complex politics of identity, this challenges us to confront the complexity so often lacking in our debates about language and race.

Vernon also paraphrased some of Basil’s words, in Afrikaans, not very long before he was murdered. They spoke of the need to remain grounded and to insist on political accountability: ‘"Almal van ons het moeders en vaders. Sommige van ons het vrouens en kinders, sommige van ons het geliefdes agtergelaat. Sommige van ons had graag gestudeer om dokters te word, of wou miskien in fabrieke werk. Al hierdie dinge was miskien vir ons weggelê. Maar so gaan dit nou een maal met revolusionêre. Ons het gesweer dat hierdie dinge nooit weer sal gebeur met ons kinders nie. Soos een van die grootste martelaars in die skadu van die galg aan sy kamerade gesê het: "Kamerade, laat ons altyd op ons hoede wees".

Chris Hani, a contemporary of Basil’s and part of the Wankie campaign, said something similar many years later, on the eve of our democratic transition:

“I think finally the ANC will have to fight a new enemy. That enemy would be another struggle to make freedom and democracy worthwhile to ordinary South Africans. Our biggest enemy would be what we do in the field of socio-economic restructuring.” He then listed the challenges: jobs, houses, health, education reform, a culture of care, fighting corruption and abusing the state. Hani ended: “We must build a different culture in this country … different from the Nationalist Party. And that culture should be one of service to people.”

Bell Hooks in an adaptation of Milan Kundera’s words, said, "Our struggle is also a struggle of memory against forgetting.”

Ariel Dulitzky is instructive when he says, ‘Memory, what one remembers, how one remembers it, why one remembers it, defines the type of society we are and we want to be, that is, our identity as a society. They not only force us to remember the victims, but also to think critically about our history of racism and apartheid, civil war, dictatorship or political oppression. Memory must not only remember and try to avoid the most serious forms of violations of human rights, but it must also be a rejection of the new forms of abusive exercise of power…Because, ultimately, the challenge for a policy of memory is not building memorials or installing sleepy statues, but creating more fair, egalitarian and democratic societies.’ (see: Memory and transitional justice - Peace in Progress magazine )

Today we remember Basil who left as a pariah and returns as a citizen of the beloved country. His short life and brave death demand that we hold his memory but, more importantly, build a more humane and egalitarian society.

We understand well his and Chris Hani’s entreaty to us all to remain alert in protecting and defending the revolution’s freedom dividend.

JUDITH FEBRUARY is a lawyer, columnist and author of ‘Turning and turning: exploring the complexities of South Africa’s democracy’ (PanMacMillan)

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here