South of the Syrian Civil War and the ongoing Egyptian political crisis, is the smouldering yet often overlooked war in Sudan. Conflict has defined the northeast African nation of 34 million people for nearly all of its 57-year existence. The details of the Sudanese narrative are obscured by the tribal and cultural fog that often arises from colonial state building and the chaotic years following colonial downfall. Unfortunately, due to this complexity, many widely swathing assumptions of the causes of the civil wars, partly true at best, get taken as fact. The wars in Sudan have been likened to an Arab-north versus Christian-south dynamic, or a resource struggle for the oil rich border territories. However, these issues are only pieces of the puzzle. The politics and power contained within such issues hinge on an even broader set of issues, ranging from a nebulous sense of ‘identity’, to very specific claims of political disenfranchisement.

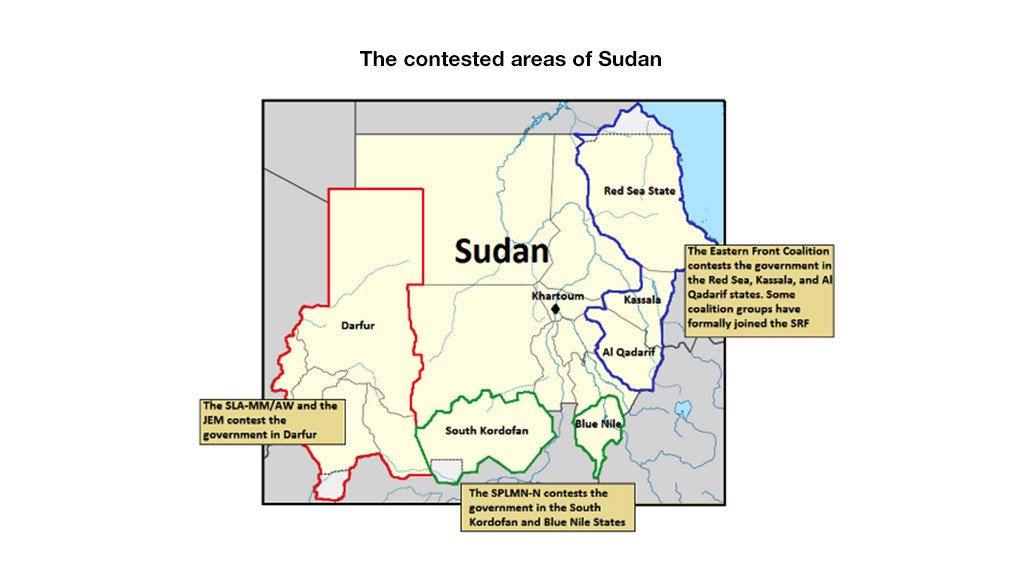

In an attempt to elucidate the Sudanese narrative, this CAI discussion paper explores the active rebellions inside Sudan, the political status of Khartoum, the government campaigns in the periphery territories, and the potential for peace. The Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), who ethnically identify with the South Sudanese, currently contest the Sudanese Government, here referred to as Khartoum (the capital), in both the Blue Nile and South Kordofan states on the border between Sudan and South Sudan. The Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF), which encompasses several Darfuri rebel groups, currently has resource claims (although Darfuri rebels began their fight in 2003 due to general claims of discrimination). In lieu of an established peace, and amidst all rebel challenges to Khartoum’s power, a consistent campaign of terror has been conducted in response, uninterrupted, by the national army. Additionally, despite the central government’s military capabilities to strike at the rebels in their various lands, several factors may indicate a decline in central power, which could ultimately prolong the conflict even further by providing incentive to the rebels. Currently the international community, including the United Nations (UN) and the United States (US) condemn the Sudanese Government and strive for peace; yet no substantial progress has been made in peacekeeping or protection of civilian life, even with one of the largest peacekeeping forces in the world on the ground.

The never-ending war: Conflict and genocide from independence to 2014

Sudan’s history, and indeed its stature as a member of the international community, has come to be defined by war. Sudan became independent from Great Britain and Egypt in 1956, but as is the case in many Sub-Saharan African nations during post-colonisation, the nation endured political chaos that led to several civil wars. The first civil war (between the north and the south) began shortly after independence and would cost an estimated 500,000 lives. Points of contention between the south and the north included oil, the enslavement of black southern Sudanese, and Khartoum’s alleged backing of tribal militias in the south. The war drew to a close in 1972, but it reawakened in 1983 when Khartoum decided to back out of the 1972 peace agreement. Two million would die in this second civil war and two million others would be displaced. While the situation looked to be resolved when the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed between the northern and southern regions, combat between the southern rebels known as the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the government kept its regularity.(2) In 2011, the southern territories seceded from Sudan through a referendum to become South Sudan, but the secession had not put an end to the constant clashes that take place in certain border areas.

In addition to the north-south conflict, there was also a major conflict and crisis in the west of the country. In 2003, at the edge of the Sahara in Darfur, a large scale rebellion against Sudan’s government prompted a massive response. Government soldiers, or the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and Arab government-backed militias (namely the Janjaweed) attacked indiscriminately in the region, killing, by some estimates, over 300,000 people.(3) Only since the Rwandan Genocide in 1994 has such a scale of state-orchestrated killing taken place. Indeed, some observers have used the term ‘genocide’ to describe the government’s treatment of the population of Darfur. A separate peace treaty was signed to resolve the fighting in Darfur in 2006.

However, in the years following Khartoum’s peace agreements with Darfur and South Sudan, Sudan itself has hardly been peaceful. Fighting has continued into 2014 and now the UN has given more attention to the issue, citing renewed violence in the Darfur region as well.(4) While Sudan’s violence seems to progress on a cyclical, never-ending basis, 2014 may be a time of major change in the country. Investigating potential fault-lines in the Sudanese political status quo may reveal that the next bout of conflicts could potentially have drastically different outcomes than the past six decades of war, which begs the question: what is different in 2014 Sudan than before?

From the palace to the provinces, Khartoum could be losing its grip

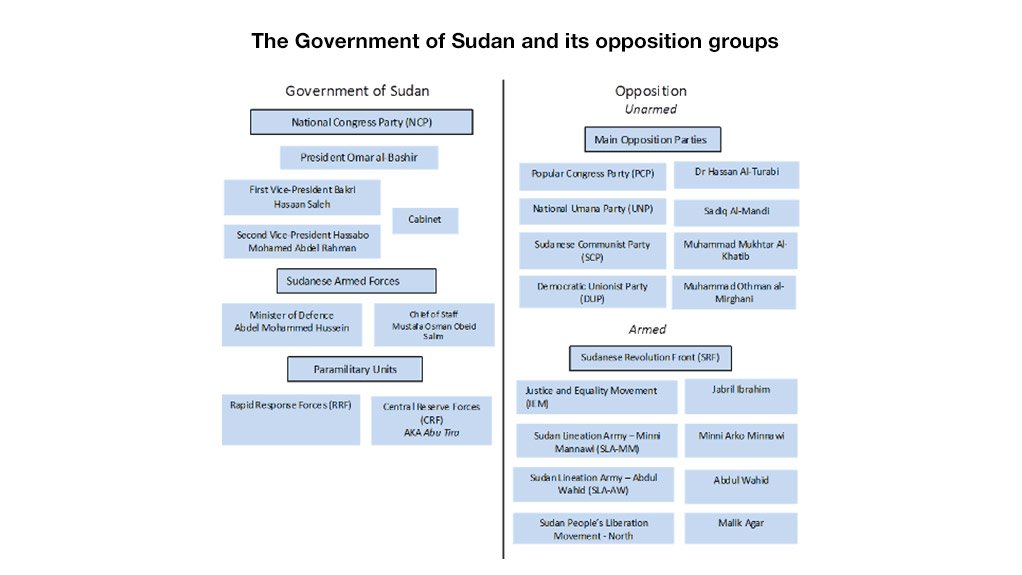

Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, came to power in 1989 through a coup d’état. Since then, he and his National Congress Party (NCP) have ruled the nation with an iron first. But their rule has also been perennially questioned, and in 2014 there are similarities between Syria’s road to civil war and Sudan’s current political powder keg. Both nations rest on the edge of a sea of Arab Spring uprisings (fearful ministers reference the issue specifically), and both nations host populations that stomach simmering dissent held back by long-lasting oppression foisted upon them by military toughs without majority cultural claims. Other dangerous signs abound as well, such as the brazen political decrees from the opposition parties and a widening anti-Khartoum rebel coalition. At the outset of 2013, several armed and unarmed opposition groups signed the ‘New Dawn Charter’ declaring the goal of overthrowing the NCP government. A government crackdown on opposition groups followed and armed conflict between Khartoum and the armed opposition has only escalated since.(5) Eastern Front rebels backed out of a formal agreement with the government and aligned themselves with the SRF coalition; now all of the rebel groups want Bashir out.(6) There have been huge food, economic, and pro-peace riots and demonstrations in Khartoum, which are caused by the economic deterioration and violence following the split with South Sudan.(7) The government has responded heavily, leaving little room for a public voice.(8) Additionally, NCP fracturing exists.(9)

Fig 1: The Government of Sudan and its opposition groups, 2014 (10)

Bashir’s regime does not have guaranteed staying power (though considerably more than Salva Kiir’s in South Sudan) and political change is desired by the opposition. The NCP excludes the major opposition movements from politics (though the different rebel groups have different levels of political possibility).(11) Thus, the rebels see no alternative to violence. When these two scenario facets are applied to the periphery territories of Darfur, Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and now north-east Sudan, a situation ripe for continued conflict and the possibility of an escalation to a full-scale civil war exists. Even more so now than in 2011, Khartoum is unable to deal with growing armed dissent and calls for change. However, unlike the south in 2011, the rebels in 2013 do not have a democratic means of resolving their qualms. But even in the case of a referendum, geographically the rebels are all Sudanese; there is no separatist element at play. Rather, the consensus among rebels seems to be that Khartoum itself must concede its power. Dialogue based progress has been sidelined by a determined opposition aiming for dismantling a regime that has only addressed them with violence. A deadly stalemate has ensued and negotiations have not picked up successfully after failing mid-February.(12)

Khartoum’s terror offensive in every direction

"Khartoum is not attacking military forces: it is deliberately attacking civilians in an effort to compel surrender or displacement or starvation of the remaining rebel forces. There is no other conclusion to be reached, given the inherent inaccuracy of the Antonov “bombers,” which fly at very high altitudes and simply roll crude, shrapnel-loaded barrel bombs out the cargo bay without benefit of any sighting mechanism.” Eric Reeves, Sudan advocate (13)

Khartoum’s response to 2013’s emboldened rebel territories has been its usual tactic of indiscriminate violence. Historically, the government of Sudan has consistently resorted to brutalising its own civilians, and campaigns of terror have taken place in rebellious territories for decades. In the 1990s, the SAF targeted civilians in the Nuba Mountains, allegedly based on ethnic considerations. During the early-mid 2000s they targeted the people of Darfur along the same lines in a more widespread, and infamous manner. Adding to this list are the areas of Blue Nile and South Kordofan (which contains the oil-town of Abyei), which have both seen intense fighting following 2011 due to their exclusion of the newly drawn South Sudan.

Fig 2: The contested areas of Sudan, 2014 (14)

The autumn of 2013 saw an aerial campaign launched against the civilians of the peripheral territories and in November 2013 the government announced “a dry season campaign for the final elimination of all armed movements” in Darfur.(15) This campaign has played itself out in a widespread escalation of violence by the government against rebels and civilians alike. A government aircraft bombed a vehicle of civilians the same month in East Jebel Marra (Darfur), killing ten instantly and injuring eight.(16)

The civilian terrorising has continued all the way through winter - even during supposed peace talks with the SPLM-N. In December 2013, a government MiG jet fighter dropped three bombs on the village in Nuba Mountains, instantly killing a mother, her three children, and three other children. On 2 January 2014, three farmers were killed by aerial attacks.(17) On 23 January an Antonov bomber attack on a mosque and village left several injured, taking the legs of the mosque’s imam and a villager.(18) On 29 January an aerial raid killed two minors. In February, even while peace talks had begun between the SPLM-N and the Sudanese Government in Addis-Ababa, Ethiopia, a MiG-SU fighter-bomber attacked and killed nine civilians, injuring 13 others in attacks on a village and a primary school.(19) Throughout February, Sudanese Air Force aerial-ground attacks took place, all on civilian targets.(20) Currently, the ‘dry season campaign’ promised by the government may have gotten off to an early start as increased Janjaweed (Darfur’s principal Arab militia) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) attacks have been reported, expanding violence into North Kordofan. The RSF, a paramilitary group formed by young men taken from Darfur and trained in Khartoum, is becoming a growing problem. Seventeen thousand refugees from renewed Janjaweed attacks now sit besieged by these forces.(21) Additionally, the Arab militias originally tied to Khartoum have reportedly turned on each other, adding even more violence to the area. Reports indicate that Khartoum has lost control of its former proxy forces.(22) Thus, coinciding with the seemingly arbitrary aerial raids, as well as threats from the central government, are paramilitary attacks and tribal harassments by groups of unknown loyalty. Camps in North, South, Central, and West Darfur are all reporting being attacked daily by “government-backed militiamen” inside and outside the camps.(23).

Paths and challenges

While South Sudan is enduring great internal strife, Sudan’s internal problems are dangerous too, in that they are indicative of a larger trend that could play out in the fashion that most developing world overthrows do -immense brutality and chaos followed by a regional reverberation of destabilising effects (Libya being a semi-regional, semi-recent example). These effects could be threats in the same manner that the current crisis in South Sudan is. Refugee and chaos spill-over is not monopolised by Juba; Sudan is also a hazard to East African security for those same reasons, and should thus be considered as such.

Unfortunately, for the sake of the civilians living in the periphery territories, as well as the Sudanese population at large, international policy has been historically useless against Khartoum. In fact, Bashir’s Sudan is one of the toughest regimes of all time in regards to sanctions, threats, International Criminal Court (ICC) warrants, and actual military strikes. Third parties such as the US, the AU and the UN intervene with much diplomatic coercion, but never with enough force - something Khartoum understands all too well. To this end, these parties have always had very little effect on shaping Sudanese policy. Sudan’s stubbornness and survival as a pariah on the international scene diffuses the gross military advantages of its foreign adversaries. US President Barack Obama’s empty promises on the Darfur genocide illustrate this fact.(24) It is the same case for the AU and UN, who have been continually impotent in defending the peoples of Darfur while being stationed there.(25) Threats to East African security (especially South Sudan) aside, this is alarming, because the NCP regime is one of the most brutal of all time, killing over 400,000 of their own citizens.(26) Additionally, NCP-controlled Sudan has existed almost entirely in perpetual warfare, whether it is against the people of the Nuba Mountains, the Blue Nile State, South Kordofan (including Abyei), or Darfur. Sudan’s regime is a tough government in a very tough neighbourhood of countries. Khartoum, despite its relative decline politically and economically after the South’s secession, would be difficult to handle in an escalated international crisis. Sudan’s historical toughness in the face of international outcry demonstrates a nation greatly capable of shrugging off foreign pressure. If there is going to be change in Sudan, it is going to come from the inside.

A scenario in which Khartoum is shaken enough by its own internal enemies to concede some of its power is hard to imagine. But it is a political possibility during a conflict period such as the one it finds itself in. Yet within this context, the situation would have to change to an extreme degree to produce such results. Should Khartoum find itself in a full scale, highly sustained, internationally backed civil war (such as in Syria) - one in which every dissatisfied group on the periphery is pitted against Khartoum with added strength - they could find themselves being forced to actually include the armed opposition in the government, or yet even worse for the NCP, total defeat. And following 25 years of oppression, extermination and mismanagement, this would most likely mean a summary decapitation of the ruling political regime with very few considerations given to Bashir’s cadre. A balance between these two outcomes is currently partly being played out through the barrels of the respective forces’ guns. Due to the recent death sentences handed out to SPLM-N movement leadership, however, the resolution of the conflict could very well be resolved solely with guns instead.(27) A political solution, under brutal zero-sum conditions such as these, seems less likely than one of the two sides losing out. The AU brokered peace process is idling at the starting line due to Bashir’s refusal to work with the rebels.(28) Bashir has placed his wager on continuing the war irregularly, terrorising the peripheral territories into submission, while the rebels have yet to muster enough strength to get even close to the security-state fortress of Khartoum.

Thus, greater incentives need to be presented to all engaged parties at new levels, however radical they may be, of negotiation terms. But, for this to happen, the ground situation of the war very well may need to change, either in favour of the terrorising Khartoum, or the steadfast rebels. With all of the unknowable, uncontrollable dynamics of the conflict at work, the dust may need more settling before real negotiating can begin – and begin it must, for while Sudan’s future is not sealed in conflict, its history indicates a deadly inclination to repeat itself.

Written by Cameron Evers (1)

NOTES:

(1) Cameron Evers is a Research Associate with CAI with a research and analysis focus on African conflict and politics in several sub-regions, particularly East Africa. Contact Cameron through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Conflict & Terrorism unit ( conflict.terrorism@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Nicky Berg.

(2) Brown, S., ’Obama’s silence on Sudan’, Front Page Mag, 18 November 2009, http://www.frontpagemag.com.

(3) 'U.N.: 100,000 more dead in Darfur than reported’, CNN, 22 April 2008, www.cnn.com.

(4) ‘Amid escalating violence, UN officials urge immediate halt to attacks in Darfur’, UN News Centre, 11 March 2014, http://www.un.org.

(5) ‘Sudan: Crackdown on political opposition’, Human Rights Watch, 26 February 2013, http://www.hrw.org.

(6) ‘Sudan’s ruling NCP to distribute invitations for national dialogue’, Sudan Tribune, 17 February 2014, www.sudantribune.com; ‘Eastern Sudan group joins SRF rebels’, Sudan Tribune, 2 October 2014, www.sudantribune.com.

(7) ‘Central Darfuri students demonstrate in Khartoum for peace’, Radio Dabanga, 20 February 2014, www.radiodabanga.org; ‘Sudanese police fire tear gas at funeral for slain student’, Reuters, 12 March 2014, www.reuters.com.

(8) Sudan repression tightened in January: HUDO’, Radio Dabanga, 10 February 2014, www.radiodabanga.org; ‘Sudan’s security authorities confiscate three newspapers’, Sudan Tribune, 5 February 2014, www.sudantribune.com.

(9) ‘Leading figure from Sudan’s ruling NCP joins splinter faction’, Sudan Tribune, 11 February 2014, www.sudantribune.com; ‘Party leader calls for postponement of 2015 election’, Sudan Tribune, 2 March 2014, www.sudantribune.com.

(10) Compiled by the author using data available at: 'Sudan', Small Arms Survey, Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan, www.smallarmssurveysudan.org; 'Sudanese opposition', Sudan Tribune, www.sudantribune.com; 'Sudan', CIA, 22 April 2014, https://www.cia.gov.

(11) ‘Party leader calls for postponement of 2015 election’, Sudan Tribune, 2 March 2014, www.sudantribune.com.

(12) ‘Negotiations between Sudan government and SPLM-N collapse’, Radio Dabanga, 16 February 2014, www.radiodabanga.org; ‘Sudan rebels not interested in peace: Defence Minister’, Ahram Online, 18 February 2014, http://english.ahram.org.

(13) Reeves, E., 'They bombed everything that moved: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan and South Sudan, 1999 – 2013’, www.sudantribune.com.

(14) Compiled by the author.

(15) ‘18,000 newly displaced arrive at South Darfur camps; militias surround El Salam’, Radio Dabanga, 3 March 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(16) Tobaya, S., ‘Aerial bombardments kill ten, injure eight in East Jebel Marra’, ReliefWeb, 29 November 2013,http://reliefweb.int.

(17) ‘Air raids kill three farmers in Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 2 January 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(18) 'Air raids on Sudan's South Kordofan violate UN Resolution 1261: SPLM-N’, Radio Dabanga, 26 January 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(19) ‘Nuba bombings kill nine as Sudan peace talks start’, Radio Dabanga, 14 February 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(20) ‘Death, injury, destruction, as Kordofan, Darfur bombed’, Radio Dabanga, 11 February 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(21) ‘18,000 newly displaced arrive at South Darfur camps; militias surround El Salam’, Radio Dabanga, 3 March 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(22) Timberlake, I., ‘Peacekeepers denied access as villages burned in Sudan’s Darfur’, Daily Star, 3 March 2014, www.dailystar.com.

(23) ‘Displaced in Darfur call for protection from Janjaweed’, Radio Dabanga, 3 March 2014, www.radiodabanga.org.

(24) Williamson, R., ‘How Obama betrayed Sudan’, Foreign Policy, 11 November 2010, www.foreignpolicy.com.

(25) Timberlake, I., ‘Peacekeepers denied access as villages burned in Sudan’s Darfur’, Daily Star, 3 March 2014, www.dailystar.com.

(26) ‘Darfur Genocide’, World without Genocide, http://worldwithoutgenocide.org.

(27) ‘Sudan rebel leaders sentenced to death’, Al Jazeera, 13 March 2014, www.aljazeera.com.

(28) ‘African Union sets April deadline for Sudan rebel peace deal’, Relief Web, 12 March 2014, http://reliefweb.int.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here