Every political organisation, including those concerned with emancipatory goals has to at times evaluate its strengths and weaknesses and that of its adversaries. During the 1980s apartheid conflict and also in the time just before the negotiated settlement some of us would meet and discuss whether the political gains, we, in the resistance forces had wrested from the apartheid regime were irreversible. These meetings were spaces for advancing political ideas and forms of organisation including trade unions that had been suppressed for much of the 1960s. We could never be complacent, we knew what had been gained could be removed.

Our political gains had accumulated over many years, starting with the Durban strikes of 1973, the Soweto uprising of 1976, the emergence of popular movements in the late 1970s, all of which made possible the formation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in 1983. Meanwhile, the apartheid regime was increasingly isolated internationally and Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was launching more dramatic attacks. These forces combined to create a situation of “ungovernability” and then the rise of “elementary organs of popular power” in the mid 1980s.

Key questions at the time, related to whether the gains that democratic forces had made would be retained and taken further to form a democratic order for the country, or would we be pushed back by state repression? We had to prepare to defend our victories and resist fresh attacks.

The state had conceded ground but generally when the apartheid regime retreated it did so in order to be in a stronger position to contain resistance or prevent further setbacks. It was not reconciled to losing ground. We had to ensure that what had been built rested on solid foundations, was based on careful organisation and was formed with adequate community consultation.

The political space that was opened in this period was highly qualified and in fact differed geographically, with varying levels of freedom and repression. In the bantustans, especially those declared “independent”, the UDF was treated as illegal and had a semi-underground existence.

Long before the national states of emergency, first declared in 1985, the Northern Transvaal was under a de facto state of emergency. While the UDF and its affiliates were actually legal organisations, the police forces in the area did not recognise this and activists faced continued harassment and detention and consequently they operated underground.

Often the level of repression, or the sense that it was imminent, made open and thorough consultation difficult. However democratic the intentions may have been some evaluations and decisions had to be taken in smaller groups rather than in meetings with the broader community. In some cities, too, larger meetings with representatives of all organisations became more risky. The need for clandestine and open work caused resentment, since some thought all decisions and discussions should be out in the open and this sometimes led to suspicion and enmity within the ranks of the democratic forces.

As the level of resistance rose, the apartheid regime decided they could not contain this without more repression. They declared repeated states of emergency, first for nine months in 1985/6 and then again for three-and-a -half years from June 1986. This resulted in smashing of many of the popular structures, but resistance continued, culminating in semi-insurrectionist conditions. Ultimately, in February 1990, the government conceded the need to unban organisations, including the ANC.

At this time, we again had similar discussions on whether democratic gains were reversible as the possibility of a negotiated settlement was being explored. The ANC was unbanned, but it was nevertheless still being subjected to armed and other attacks, which made its safety and future legality uncertain.

It is a paradox that the question of the irreversibility or otherwise of gains made should need to be raised again more than 20 years after the first democratic elections. I have myself suggested this. (See, for example, Recovering Democracy in South Africa, Jacana Media, 2015, chapters 7,13, 16). And it is also being voiced in the recent book of Moeletsi and Nobantu Mbeki, A Manifesto for Social Change. How to Save South Africa. Picador Africa, 2016) where they suggest that many democratic institutions are being undermined and that democracy itself is being reversed. The book argues that there is in fact a low intensity war against the poor, who do not see improvements but see their life conditions worsening. (See, for example, pages 2, 8, 12, 20-21.) This is in the context of an argument that the “stunted” capitalist growth path based on consumption, currently followed, is unsustainable.

The same question is now being asked at a time when sections of business, in concert with a segment of the ruling elite close to President Jacob Zuma and his allies engage in and appear impervious to exposures of their corrupt actions. They are determined to cream off whatever they can from public funds and public entities, no matter what the costs to the fiscus. Just this week there have been more than one revelation of irregular contracts involving the president’s close friends, the Guptas with ESKOM and allegedly also with PRASA. In each case, the president’s son Duduzane is a beneficiary.

If we ask whether the gains of 1994 are reversible one may need to reply that the intention of those who pose a danger is not in the first place to attack democratic rule. There is no direct attack on the right to vote, a universal achievement which represented an historic victory. But the fact is that those who are elected now have access to public funds, are able to determine who gets state contracts and how they are implemented or whether they are executed at all, and these influences undermine the power of that very vote.

The killings that are underway over electoral lists, mainly of the ANC, have nothing to do with political factions. These killings and other attacks are not attempts to influence the political choices that voters may have, but which individual is elected. The groupings do not represent particular views over the direction that the state at one or other level should take economically or in any other way.

The alleged manipulation of the electoral list process has led to protests and also violence. The violence is not over the pillage that ensues after individuals hold office, but over whom it is that will have access to public resources. Between those who may be in conflict over positions there is a shared assumption that there is to be continued pillage of state resources.

So the resources of the state are being stolen, that which is available to meet basic needs, to provide electricity, water, healthcare and other needs and ensure that they are maintained, is depleted. People see their vote is having no effect and that they are unable to negotiate a resolution of their problems with those who bear responsibility and they protest. Increasingly their actions are met with a violent response from the state.

The state now stands over and against the people whom it is meant to represent. It is a paradox that this government depends on the “underclass” to be elected, that its primary voting constituency is the poorest of the poor.

There is no doubt that the lives of very many people have improved substantially over the last 22 years, despite the uneven provision of basic needs and inadequate maintenance. But this is being eroded. It is this “underclass” that is increasingly falling outside the state welfare safety net.

The democratic gains of 1994 and constitutionalism are under stress, notably in the diversion of funds. Key state institutions are being undermined or used for partisan political purposes of a grouping loyal to President Zuma, for example, the National Prosecuting Authority, South African Revenue Services, and the Hawks.

But there are countervailing forces. The Treasury has for the last 22 years sought to ensure that government spending is regularised. This may account for the removal of Finance Minister, Nhlanhla Nene, and an attempt to replace him with a more pliable person likely to reverse this trend. It may also account for the continued threats of arrest or prosecution hovering around the current Minister, Pravin Gordhan.

Neither government, the ANC or its political allies, or business, or labour, are monoliths. There are a number of reasons, other than attachment to democracy and constitutionalism that may determine why one grouping within the ANC may resist the current undermining of constitutionalism and see the course pursued by Zuma as dangerous and threatening not only to democracy but to ANC rule.

Not all sections of the emerging black capitalist class or the ANC approve of a consumption orientated and parasitic capitalism. Big business (mainly white owned) and some sections of the political leadership favour more regularised ways of operating government’s relationships with business and fear a collapse of the economy and state functioning.

As these developments unfold, a marked feature of the present is that we, as citizens, tend to be spectators, not actors in the political life of the country. With official political life depoliticised, there is an urgent need for those who still cling to emancipatory goals to develop alternative avenues for defending and enhancing democratic rights. This may require building additional political outlets where democratic and empowering views can find expression and potentially have some effect.

[Note: This article was written before the current violence in Tshwane and is not intended as a commentary specifically related to developments that have taken place there]

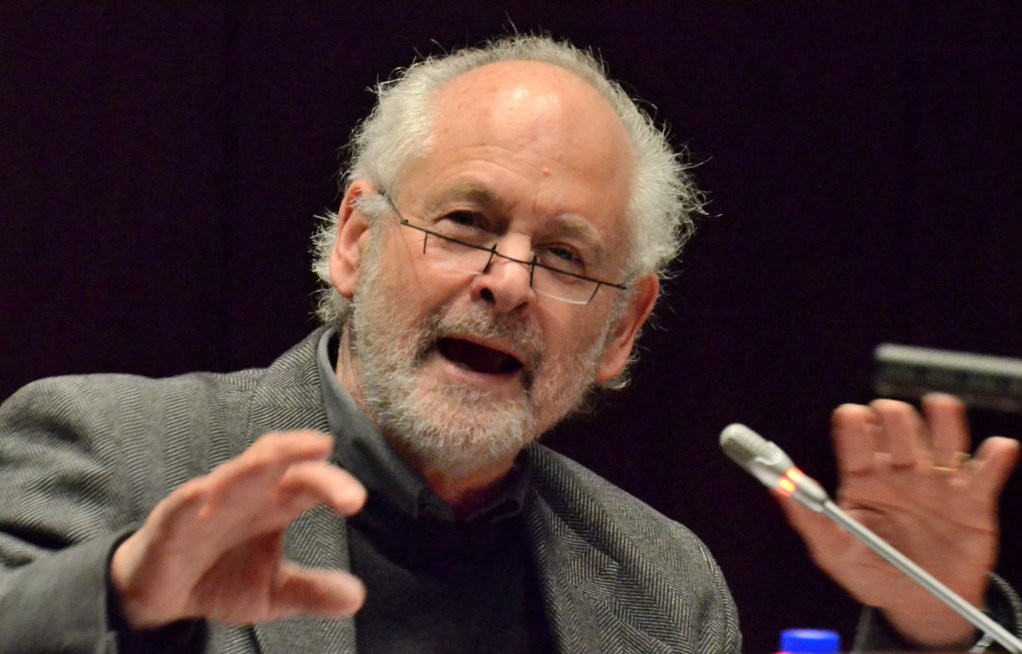

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. Much of his life was spent in the struggle against apartheid and in building the new democratic order. He served lengthy periods as a political prisoner and under house arrest. Currently he is a professor attached to Rhodes University and UNISA and he has authored or co-authored Inside Apartheid’s Prison (2001), 30 Years of the Freedom Charter (1986) 50 Years of the Freedom Charter (2006), The ANC Underground (2008) and most recently Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana and Lynne Rienner, 2015). He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here