In recent years, the South African Police Service (SAPS) has come under the spotlight due to the increasing number of incidents in which civilians have been assaulted or even killed by the police. Cases such as the August 2012 killing of 34 mineworkers in Marikana in the North West province,(2) the death of Mido Macia after being dragged behind a police van in Daveyton in Gauteng province,(3) and the ruthless March 2014 assault on Clement Emekeneh in Cape Town (4) are just the tip of the iceberg of the ever escalating brutality of the SAPS. Although the majority of reported cases of police brutality are isolated incidents, they do nonetheless point to brute behaviour which in itself evinces a systemic problem.

This CAI paper attempts to locate the brutality of the SAPS within a wider culture of violence that characterises post-apartheid South Africa. It is herein contended that even though the SAPS has inherited a violent past from apartheid, there is need to take responsibility for the present-day behaviour of the police force, instead of using apartheid as a convenient scapegoat. It is also asserted in this paper that there is urgent need to police the police, if the prevalence of brutality by law enforcement agents is to be curbed.

South Africa’s history of violence

Dariusz Dziewanski, a researcher and consultant in international development, stresses that “violence in South Africa is nothing new. Both the devastating effects of violence, and the risk factors underlying it, have existed before…and will continue to exist.”(5) The official crime statistics for 2012/13 prepared by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) show that there has been a steady increase in violent crimes in South Africa. For example, compared to the 2011/12 reporting period, there was an increase of 4.2% in murders, 1.5% in sexual offences, and 4.4% in aggravated public robberies.(6) How can these increasing levels of violence be explained.

Violence in South Africa is complex because its causes are embedded in its specific socioeconomic and historical context. To begin with, South Africa possesses enormous reserves of mineral resources and has robustly invested in infrastructural developments. Be that as it may, these resources have been in the hands of the white minority for a long time. In the post-apartheid era, an increasing number of blacks have joined the minority white in the elite rich, and the divide between the rich and the poor has continued to widen unabatedly. Ryan Leonora Brown, editor of the Africa Monitor blog, notes:

South Africa now has the second widest gap between its rich and its poor in the world. And those who live among the world’s economic elite and those who survive on a few dollars a day don’t inhabit distinct worlds. They live and work in the same towns, cities, and companies. The distance from Johannesburg’s Sandton suburb–the richest square kilometre in Africa–to a slum without running water is all of three miles.(7)

She concludes in this line of thought that “the rising income gap, coupled with an official unemployment rate of 25 percent, have helped give rise to a highly organized criminal element across the country. But many say that the economic explanation doesn’t tell the full story.”(8) If the unequal distribution of wealth cannot fully explain the prevalence of violence in post-apartheid South Africa, then there is need to offer a historical examination of the problem.

In many instances, the current violence that is prevalent in South Africa is attributed to the apartheid legacy, which was characterised by brutal and violent use of force by law enforcement agents. President Jacob Zuma alluded to this fact when he stated that apartheid was directly responsible for creating a culture of violence:

I don't think as a nation we just became violent overnight. Violence is a direct consequence of apartheid. Apartheid was a very violent system. So violent that even if you peacefully demonstrated, they would shoot at you and kill you. That called the reaction from those who were oppressed to become very violent in fighting apartheid.(9)

Pertinent as Zuma’s explanation may be, it is important to point out that 20 years have passed since the fall of the apartheid regime. Can the violence of apartheid continue to be used to explain the ongoing violence of South African societies? For how long can apartheid be held responsible for the ills that plague post-1994 South Africa? Mike van Graan, Executive Director of the African Arts Institute and UNESCO Technical Expert on the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, expounds, “While it is true that apartheid legacies remain manifested in many aspects of our lives, there are many choices that have been made and things that have occurred in a post-apartheid society which we would not have expected.”(10) Although violence played a pivotal part in the apartheid regime and in its final overthrow, there is need for South Africa to look beyond the violent past as it grapples with its ideals of creating a ‘rainbow nation’.

The police force provides a prime example of the violence that is so prevalent in South Africa. Numerous incidents of police brutality have been highly publicised in local and international media. The most publicised of these cases were the mass killing of miners on strike in the North West province and the killing of a taxi driver in the township of Daveyton in Gauteng. The first case occurred on 16 August 2012, when a workers’ strike at Lonmin Mine in Marikana ended with police cornering the striking workers and opening fire on them. A total of 44 miners lost their lives and at least 78 others were injured. The killing of these miners was caught and broadcast on live television. A commission of inquiry set up by President Zuma has yet to conclude its investigations, as of the time of writing.(11) In the second case, on 26 February 2013, a Mozambican immigrant, Mido Macia, was arrested by the police for causing traffic congestion. He was tied onto the back of a police vehicle and dragged around the township of Daveyton in full view of local residents. This incident was filmed on a phone and the video immediately went viral on social media. Macia later died in police custody due to head injuries and internal bleeding. To date, none of the eight police officers involved in the death of Macia have been prosecuted.(12)

These and other incidents reveal a number of issues. Firstly, it is evident that police have been known to use unnecessarily excessive force. Secondly, it appears that police officers are not conversant with the code of conduct of the SAPS. The next section attempts to analyse the manner in which there is need to police the police if their current modus operandi is to be improved.

Policing the police

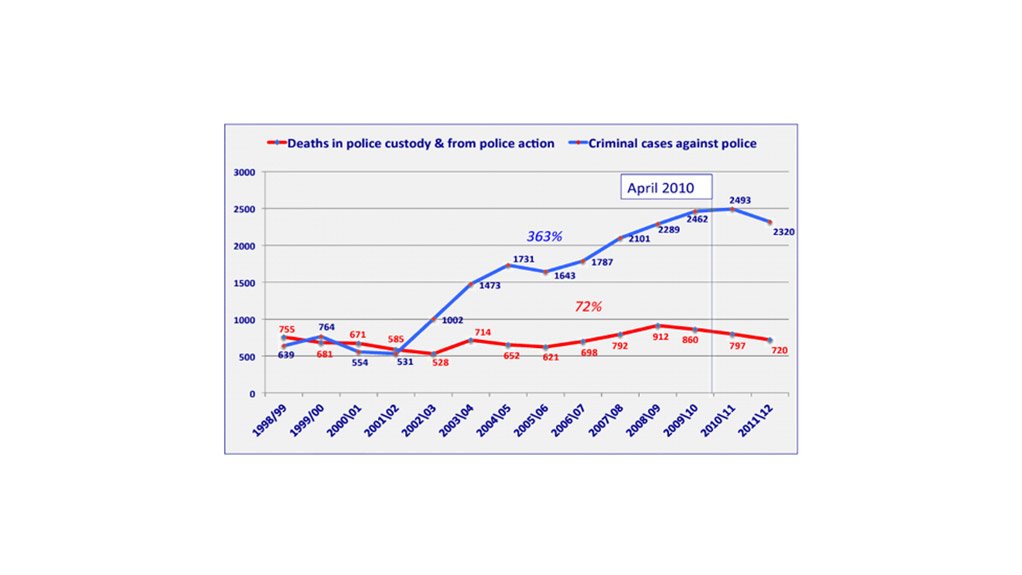

Award-winning Wits Justice Project senior journalist Carolyn Raphaely observes, vis-à-vis the SAPS, that “an entrenched culture of impunity, with little regard for consequence or culpability, indicates that South Africa has learnt little from the lessons of the past.”(13) Assault, torture, beatings, as well as killings have become part and parcel of the modus operandi of the SAPS. Although legislation does not condone police brutality, Raphaely reveals that police officers involved in brutality and human rights violations are rarely brought to book. According to her, “Only one conviction was obtained in 217 deaths allegedly at the hands of the police or in police custody, as investigated by the directorate in Gauteng in 2011/12.”(14) In 2013, the Parliament of South Africa promulgated the Prevention and Combating of Torture of Persons Act, which sought to protect and promote human dignity, including that of individuals who have been arrested and are in police custody. It is hoped that this Act will play a central role in combating the brutality and impunity of the SAPS. For now, the cases of police brutality stand at alarming levels. The graph by Dr Johan Burger, Senior Researcher at the ISS, illustrates the high levels of criminal cases against police:

Figure 1: Fatalities and criminal cases against the police (15)

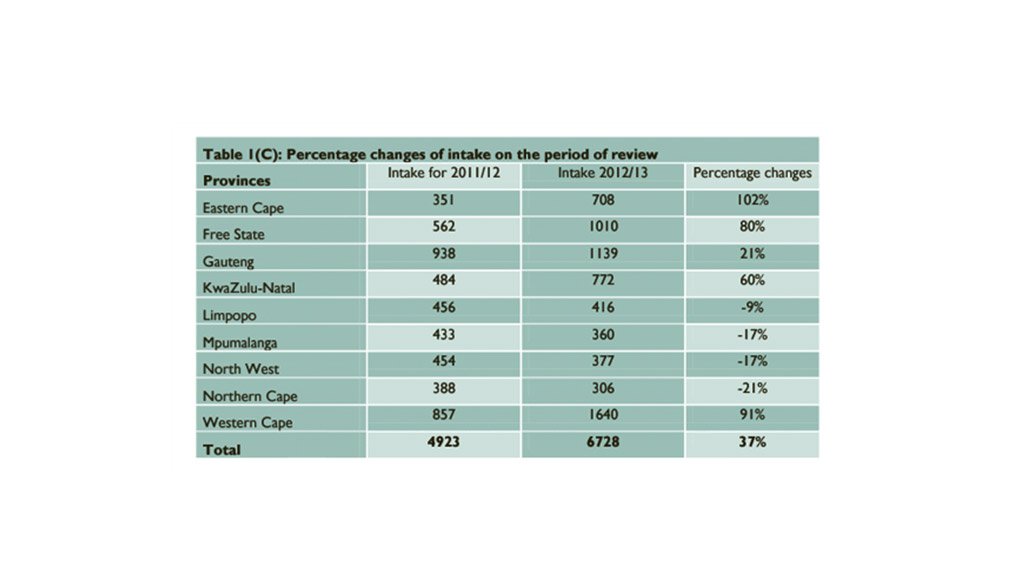

Although this graph shows a slight decrease from 2010 in levels of criminal cases against the police as well as police-related deaths, the figures still remain unreasonably high. A total of 2,320 criminal cases against the police in the 2011/12 reporting period alone is intolerable. Furthermore, the 2012/13 report by the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) shows that the number of cases reported involving police misconduct and brutality continue to rise alarmingly. The table below shows the changing levels of reported cases between the 2011/12 and 2012/13 periods of review:

Figure 2: Number of cases reported to the IPID (16)

Such statistics occur even though there is a Code of Conduct of the SAPS, which explicitly states that in order to achieve a safe and secure environment, the organisation seeks to “contribute to the reconstruction and development of, and reconciliation of the country,” “uphold and protect the fundamental rights of every person,” and “act impartially, courteously, honestly, respectfully, transparently and in an accountable manner.”(17) Inasmuch as this code of conduct is laudable, police officers clearly do not always respect it in practice. The cases previously mentioned on police brutality illustrate that law enforcement agents act, in many instances, in a manner that disrespects human rights and dignity.

The IPID was formed in April 1997 to deal with cases that involve improper discharge of duties by the police. The prime duties of the IPID involve investigating crimes allegedly committed by police officers, including violations of SAPS policy as well as national legislation. Section 4 of the IPID Act regulates the relationship between the IPID and state organs in such a manner that its operations remain impartial and independent. In its 2012/13 annual report, the IPID disclosed that “a total of 6,728 cases were received by the IPID during the reporting period. The majority of the cases received were assault cases, namely 4,131. Seven hundred and three of all cases received were other criminal matters, whereas 670 were complaints of discharge of official firearms and 431 of the cases were deaths as a result of police action.”(18) Interestingly, of the 6,728 cases received by the IPID, only 84 convictions were effected. This means that just 1.2% of criminal cases opened against law enforcement officials during that time resulted in a conviction. Such statistics have led Burger and Cyril Adonis (Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation) to author a report whose title likens the independent investigative directorate to a “watchdog without teeth.”(19) Reiterating this same point in an interview on the programme South 2 North on Al-Jazeera, Redi Tlabi pointed out to Commissioner of Police Riah Phiyega that the IPID might not be as effective as the legislation that led to its creation. Tlabi affirmed that in the past, the “IPID has complained that the recommendations they make to the SAPS don’t get implemented and the police actually close rank.”(20) It is perplexing that although there are legislation and investigative directorates in place to ensure that the SAPS operates efficiently and in a manner respecting human rights and dignity, cases of police brutality and impunity continue to soar. What worsens this situation is the fact that taxpayers have to literally pay for the brutality of police. According to a report by the ISS, the cases of police brutality brought against the SAPS in 2013 have had serious “consequences for the tax-payer as [SAPS] was facing civil claims valued at more than R480 million [US$ 46 million] in relation to assault, and R1.1 billion [US$ 100 million] related to shooting incidents. Total claims against the police have doubled in the past two years to R14.8 billion [US$ 1.4 billion].”(21)

If legislation and the IPID are unable to govern and regulate the SAPS and its operations, it is necessary to ask what should be done to ensure that the cases of police brutality decrease. The next section discusses areas that require critical attention, if the reputation—and more importantly, the conduct—of the SAPS are to be rehabilitated.

Searching for potential solutions

Police brutality should not be examined in isolation. It has to be considered in the broader socioeconomic and political context in which the police force operates. Graeme Hosken, a journalist who specialises in crime, observes, “Negligent police management, poor training, disrespect for law and order, criminal members within police ranks and blatant disregard for internal disciplinary procedures are the chief causes behind the scourge of police brutality gripping South Africa.”(22) If police brutality is to be stamped out, then it is imperative that all members of the SAPS adhere to the legislation governing their operations. Meaning, they must be held accountable for violating operational policy.

Moreover, there is need to properly train new recruits as well those who are already active members of the police force, not just on how to investigate crimes but also how to conduct themselves as they discharge their duties. Speaking at a conference held in April 2013, Lt. Gen. Mzwandile Petros, Police Commissioner of Gauteng, accepted that “the effective transformation of the police and improving the quality of the new recruits were some of the mechanisms that could be used by the government to address the challenge of police brutality.”(23) Lt. Gen. Petros highlights an important issue here: the quality of police recruits. In the last decade, there has been a massive drive to expand the police force. This has unfortunately resulted in compromising quality for the sake of quantity. For example, in 2013, the ISS reported that “1,448 serving police officials had convictions for serious crimes ranging from murder to rape and assault.”(24) If the SAPS wants to increase its human resources base, it has to do so without compromising the quality of the police officers that are recruited. Having a police force composed of criminals is a self-defeating exercise if one of the main objectives of the SAPS is to ensure that offenders are brought to justice.

Leadership is another salient aspect that needs to be examined. An analysis of speeches of certain political leaders and those in charge of the police shows a dearth in focused and exemplary leadership. For example, in 2008, Susan Shabangu, then Deputy Minister of Safety and Security, instructed the police to shoot to kill. She stated, “You must kill the bastards if they threaten you or the community. You must not worry about the regulations—that is my responsibility. Your responsibility is to serve and protect. I want no warning shots. You have one shot and it must be a kill shot.”(25) Such a controversial statement by a high-ranking minister is not only unfortunate, but can be seen as a catalyst in encouraging policemen to employ extreme violence and brutality. Another example is by the former Police Commissioner Bheki Cele, who advised the police in 2007 to use lethal force and always “aim for the head”(26) whenever under attack. These instructions from those in leadership positions incite police officers to think that they can do whatever they want, and that they are above the law. The police thus use brutal force while fully cognisant that they will receive the backing of the political leaders. Burger explains in this respect that “police brutality could not simply be blamed on a few ‘bad apples’, which is an approach taken by police leadership to shift attention from their own shortcomings.”(27) He concludes in the same vein that “the root of the problem lies in poor command and control. This was the finding of a two-year process in which a SAPS Policy Advisory Council had inspected three quarters of the country’s police stations.”(28) Political leaders, as well as the commissioners of the SAPS, need to lead by example, particularly in the statements that they issue concerning the modus operandi of the police. Instead of encouraging the use of brutal force, these influential people should be at the forefront of enlightening police officers on the merits of restraint in the discharge of their duties.

Burger notes that the transformation of the SAPS, particularly in regards to police brutality, should be done in a manner that aligns itself with the National Development Plan. He points out:

If we are to do away with police brutality, we need to start with the implementation of the recommendations of the National Development Plan, which are constructive and good. The National Development Plan recommends that the police code of conduct and code of professionalism be linked to promotion and discipline in the service, and that recruitment should attract competent, skilled professionals.(29)

A multifaceted approach is therefore required in eradicating police brutality in South Africa. On one hand, there is need to address the violent and brutal past that was inherited from the apartheid regime. On the other hand, it is imperative to look beyond apartheid and work on creating a competent and skilled police force through the recruitment of properly qualified and trained individuals.

Concluding remarks

The SAPS has accomplished many achievements since the end of apartheid. Nathi Mthethwa, South Africa’s police minister noted in a May 2013 speech that “contrary to the current discourse, more people are beginning to feel safe.”(30) He observed, for example, that in the previous three years, sexual offences had reduced by 11.9%, bank robberies had gone down by 64.2%, and cases of attempted murder had reduced by 21.8%. All these achievements are, however, overshadowed by the ever increasing cases of police brutality. It is overdue that the SAPS transform the manner in which some of its employees carry out their duties. The current culture of brutality and impunity that characterises its operations is not only unsustainable but also self-defeating, given that the primary duties of the police are to stamp out all forms of crime and protect the public. Mass recruitment of police officers, while justifiable in the face of elevated levels of crime, should not result in the enlistment of poorly trained or unqualified officers. Current brutality of police and general policing standards in South Africa are unacceptable for a democratic country. Firm and resolute action is required if the SAPS is to be trusted, not feared, as South Africa grapples to heal from its violent past.

Written by Gibson Ncube (1)

NOTES:

(1) Gibson Ncube is a Research Associate with the Rights in Focus unit at CAI. His key research interests are in gender and queer studies as well as human rights. Contact Gibson through Consultancy Africa Intelligence's Rights in Focus unit ( rights.focus@consultancyafrica.com). Edited by Kate Morgan. Research Manager: Mandy Noonan.

(2) Chapple, I. and Barnett, E., ‘What’s behind South Africa’s mine violence?’, CNN, 14 September 2012, http://edition.cnn.com.

(3) Parker, F., ‘Cops drag man to his death – for stopping traffic’, The Mail and Guardian, 1 March 2013, http://mg.co.za.

(4) Ojeme, V., ‘Federal government demands action from South Africa over assaulted Nigerian’, The Vanguard, 13 March 2014, http://www.vanguardngr.com.

(5) Dziewanski, D., ‘The real face of violence in South Africa’, The Mail and Guardian, 13 March 2014, http://www.thoughtleader.co.za.

(6) ‘Factsheet, South Africa: Official crime statistics for 2012/13’, Institute for Security Studies, September 2013, http://africacheck.org.

(7) Brown, R.L., ‘How violent is South Africa?’, The Christian Science Monitor, 22 February 2012, http://www.csmonitor.com.

(8) Ibid.

(9) ‘Violence comes from apartheid: Zuma’, News24, 15 February 2013, http://www.news24.com.

(10) Van Graan, M., ‘The A to Z of things we cannot blame on apartheid’, The Mail and Guardian, 13 January 2014, http://www.thoughtleader.co.za.

(11) Chapple, I. and Barnett, E., ‘What’s behind South Africa’s mine violence?’, CNN, 14 September 2012, http://edition.cnn.com.

(12) Parker, F., ‘Cops drag man to his death – for stopping traffic’, The Mail and Guardian, 1 March 2013, http://mg.co.za.

(13) Raphaely, C., ‘Apartheid culture of police brutality still alive today’, The Mail and Guardian, 31 January 2014, http://mg.co.za.

(14) Ibid.

(15) Burger, J., ‘Police brutality: Reasons and Solutions’, Institute for Security Studies, 11 April 2013, http://www.issafrica.org.

(16) ‘Independent Police Investigative Directorate Annual Report 2012/2013’, IPID, August 2013, http://www.ipid.gov.za.

(17) ‘Code of Conduct of the South African Police Service’, October 1997, http://www.saps.gov.za.

(18) Ibid.

(19) Burger, J. and Adonis, C., 2008, ‘A watchdog without teeth’, Institute for Security Studies, http://www.issafrica.org.

(20) Tlabi, R., ‘Who polices the police?’, South2North on Al Jazeera, 16 March 2013, http://www.aljazeera.com.

(21) ‘Warning lights flashing: A brutal police force with a reputation for corruption’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 August 2013, http://www.issafrica.org.

(22) Hosken, G., ‘Why SA cops are so brutal’, Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 26 May 2011, http://www.csvr.org.za.

(23) ‘Understanding police brutality in South Africa: Challenges and solutions conference’, 11 April 2014, http://www.issafrica.org.

(24) ‘'Warning lights flashing: A brutal police force with a reputation for corruption’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 August 2013, http://www.issafrica.org.

(25) Ellis, M., ‘Police brutality: A threat to rights?’, iAfrica.com, 24 March 2014, http://news.iafrica.com.

(26) Plantive, C., ‘SA cops urged to aim for the head’, The Mail and Guardian, 22 July 2007, http://mg.co.za.

(27) Burger, J., ‘Understanding police brutality in South Africa: Challenges and solutions’, Institute for Security Studies, 11 April 2013, http://www.issafrica.org.

(28) Ibid.

(29) Ibid.

(30) Rademeyer, J., ‘Police minister’s speech a glass half full’, Africa Check, 5 June 2013, http://africacheck.org.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here