There was a time when I would not have written about the ANC, on the eve of the 8th January anniversary statement. I would have waited to see what was in the statement and incorporate what I learnt from it or engaged with it in whatever I was writing. Nowadays, however, there is no reason to wait. There is no reason to expect new insights or fresh thinking.

Mondli Makhanya writes: "The statement used to have great meaning when the ANC itself had great meaning. In the decades of banishment, the January 8 message from the ANC's then president, OR Tambo, was eagerly anticipated in the army camps, exile operations in foreign capitals and inside the country. Announced on Radio Freedom [broadcast by the ANC from various independent African states-RS] and distributed in pamphlets in the dead of night throughout the land, it was a source of hope, inspiration and direction in dark times. Those who heard and read them hung on to Tambo's words as though they were a page from an apostle whose gospel writings were left out of the New Testament. The day was sacred. Even after 1994, people-not only the ANC membership but also the markets and the general public-waited with bated breath for Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki's statements." ("Rose-tinted glasses must go", City Press 5 January 2019, Voices page 2, likely to be available online by the time this article appears).

This is not because the leaders of the ANC or authors of the statement are lacking in intellectual skills and training of various kinds. What has happened is that the ANC has slipped into decay and in such an environment, there is little value placed on debate. In a period of cynicism, there is little that evokes emotions, passion and conviction.

Right up until the 1990s there used to be some excitement about ideas in the ANC and its allies, thrashing out problems, sharing what comrades had read. I remember young African activists with thick theoretical books by authors like Amilcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon or Antonio Gramsci under their arms, books that no longer had to be read secretly because of the unbanning of the previously illegal organisations. That culture of ideas has disappeared. The ANC is preoccupied with remaining the ruling party and battling over positions.

There was a time, not so long ago when the ANC appeared likely to remain the ruling party indefinitely. For many scholars, this "dominant party" phenomenon was a barrier to "consolidating" democracy in South Africa. To be a consolidated democracy, there needed to be a reasonable likelihood of a "circulation of elites", i.e. an opposition party displacing the ruling party – something which then appeared highly unlikely to happen. This was part of a wider conservative trend, mockingly referred to by its critics as "consolidology". My personal discomfort with this approach was that one could not conjure up support for political parties with ambiguous histories under apartheid, to displace the ANC, which had a long history of hard and difficult struggle. Also, the understanding of democracy advanced, was almost purely as an electoral phenomenon, with the masses having to be passive onlookers after casting their votes. This did not sit well with those of us who had been through the popular power period of the 1980s, where democracy was understood as an ongoing process, not restricted to periodic voting.

The problem of "dominance" has been resolved for these transition theorists insofar as the ANC's impunity has been punctured electorally. But although the ANC received shocking results in the 2016 local government elections, losing control of three metros, the DA has in fact forfeited what it gained in most cases. It lost Nelson Mandela Bay, Johannesburg and may well lose Tshwane in the weeks ahead. The DA is itself in a deep crisis, going beyond these metros, that could lead to its disintegration as a major political force.

But that does not mean that the ANC is a stable ruling party and leader of government. It is in the grip of multiple crises -as leader of government and in the organisation itself. Even below the official count of current crises, like ESKOM and SAA, there are a series of mysterious bombings of trains and drive-by shootings, as happened on New Year's Eve in Melville and a few days later with trains in Bloemfontein. Words like "senseless" or "mindless" convey opprobrium, but they obliterate the causality that appears to be hidden. (https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-01-05-prasa-calls-for-arrests-after-senseless-torching-of-24-train-carriages-in-bloem/). There is no evidence of coordination of the various attacks, but it needs investigation.

The ANC used to chant the slogan "ANC lives, ANC leads!" and it would hardly claim to be acting that out now. The ANC's organisational crisis is one of apparently irresoluble divisions, between what commentators call "factions", but are not divided by definite ideological concerns. Nor are these simply the heirs to Jacob Zuma fighting those who want a "clean-up" and are intent on ridding the country of state capture and corruption.

Who supports who is not clear. Some of the supporters of Zuma and current president Cyril Ramaphosa hover in a zone between loyalty to either leader, seeing what will benefit or protect them most as the conflict develops. The Ramaphosa camp is not stable, and it may well be that the Zuma grouping has more coherence, with its greater accommodation of those whose honesty has come into question.

In earlier periods of ANC history, battle lines were drawn on political or ideological lines. Today, one can safely ignore talk about "Radical Economic Transformation" (RET) and "White monopoly capital" (WMC) and similar pseudo-revolutionary phrases. The ANC is now an organisation that is depoliticised and lacks a common vision for the country. That is not to say that it does not take or support decisions that have an ideological impact but that the support base of one or other "faction" is not based on such positions. These allegiances are forged through patronage and corruption. At the least, the desire for and provision of positions may entail a patron/client relationship (but not necessarily be corrupt). Alternatively, it may involve the desire for a "cut in the action" which may be or has often been corrupt.

From the lowest to the highest rungs of the organisation, membership and positions are linked with acquiring benefits, in a harsh economic climate. At the lowest level, in a situation where many people experience dire poverty, election to an ANC structure may lead to becoming a councillor and a modest salary, which is important in current conditions or better still, may provide access to more lucrative work or contracts. The struggle between those competing for such positions has led to violence and murders.

The ANC has retained much of its support base through appearing to be the party that will deliver certain benefits, like social grants, fostering the belief that this could come under stress if the organisation were no longer in power.

In the aftermath of the Zuma era, those who were implicated in the looting are fighting attempts to bring them to book and possibly serve prison terms. The likelihood of that happening has increased with revamping of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) and, albeit unevenly, work by some sections of the South African Police Services (SAPS) specialised units.

But corruption extends beyond the Zuma camp, with the (Deputy Chief Justice Raymond) Zondo commission demonstrating the alleged implication of some who are seen as Ramaphosa loyalists, as with a middle-ranking MP, Vincent Smith and Minister and ANC Chair, Gwede Mantashe, both allegedly benefitting from the Bosasa largesse. One does not know what else is not yet in the public domain that could lead to further claims against those seen as part of the Ramaphosa camp.

The anxiety over possible prosecution or losing positions may account for the attacks on Pravin Gordhan, as Minister of Public Enterprises, by the EFF and Zumaites. Gordhan spearheads the movement to clean up state-owned enterprises (SOEs). There has generally been silence on the part of the ANC as Gordhan has continuously come under fire. If Gordhan is doing what the ANC has instructed him to do and what the president wants, given that the "new dawn" was widely understood to be a break from the pillage of the Zuma years, why is Ramaphosa generally silent while most of the attacks on Gordhan take place? If Gordhan is doing what he is supposed to be doing and is coming under attack for this, surely the president should continually reinforce his work, saying "I back Minister Gordhan" or "what Gordhan has done is what we instructed and conforms to our policies".

We do not know what constrains some of the Ramaphosa camp from providing this support., (though there have been isolated and limited incidents of backing expressed for Gordhan). But there has been a glimpse of what may be below the surface, in the revelations of spending on the CR17 Ramaphosa campaign for the ANC presidency, which presented a troubling picture. It entailed transporting voters from provinces, sometimes paying their outstanding membership fees and monitoring their accommodation and movements in Johannesburg, to ensure that what was paid for was not going to be wasted through their being "poached" by the other camp and becoming voters for Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma.

ANC HQ: Presidency under fire

But Ramaphosa himself has been under constant fire -from ANC HQ, which is controlled by Ace Magashule and his allies. For much of 2019, we witnessed outright acts of disloyalty and defiance of Ramaphosa, on the part of those associated with Magashule, making statements or taking actions that struck a different note from that of Ramaphosa or seeming to undermine the ANC and state presidential authority of Ramaphosa.

In this context, where one inherits a divided organisation and leadership, it is not a space to simply be a "nice guy". Ramaphosa is the president of the ANC, but he does not seem to have the stomach for the internal battle that needs to be waged in order to assert his authority. When one is dealing with the type of opponents, he has this cannot be resolved through acts of cordiality. But, to a significant extent, he appears to have conceded the space so that there is little counterweight in ANC structures to the discordance of Magashule and his allies.

Lack of vision

ANC leader and former Deputy Minister of Finance, Mcebisi Jonas (author of a significant book, After Dawn. Hope after state capture, Pan Macmillan, 2019). has called for a new social compact to rededicate key players on the future direction of the South African state.

I agree with the need to find ways of rejoining those who have drifted apart, in the quest for democracy, development and growth. But in reconceiving a social compact in 2019, we need to move beyond agreement between business, organised labour and government. We also need to augment the power of the ballot box.

The ousting of Zuma derived not only from the unhappiness that developed within the ANC but from a range of sectors of society -business, actors from social movements, NGOs, professions, amongst others. These are human resources that enrich our democratic life and they need to express their contribution on a range of occasions, not only on an oppositional basis but in addressing other crucial questions like climate change, the culture of violence, specifically gender-based violence, xenophobia and other issues.

The government of the day needs, also assisted by such organisations and sectors, to be in better touch with the problems people are facing in their daily lives in insecure neighbourhoods and transport with a dire state of social services, amongst others.

All of these endeavours need to contribute towards developing a vision for the future, a fresh vision, that elaborates on the Freedom Charter, the constitution and other documents, without denying their continued validity. There are now other pressing issues that need public attention, obviously including addressing how current energy policies play havoc with our climate.

What is the future role of the ANC?

What role the ANC will play in future developments is unclear. It may not be able to lead an emancipatory process to develop a new social compact. But that does not mean it ought not to be a significant part of it.

In remarking on the depoliticisation and lack of vision on the part of the ANC it is important to understand that the ANC is more than one thing. It has crooks but it also still embraces some who have joined and been members for very long on the basis of belief in freedom, compassion towards the underdog and the poor. After the Melville shootings, someone told me that the local ANC branch had been there comforting people. This is not the dominant image we have of the ANC in 2020, but it is still part of what some people consider it to mean to be in the ANC -to act with empathy towards the injured, marginalised and the poor. In earlier periods the ANC was not the same thing in big cities as in the rural areas. It has always had more than one character, with reference points differing by virtue of distinct life experiences.

The argument for a new force must consequently not be conceived as necessarily anti-ANC. It is up to the ANC to demonstrate its willingness to renew itself and play a significant part in rebuilding the country and its freedoms.

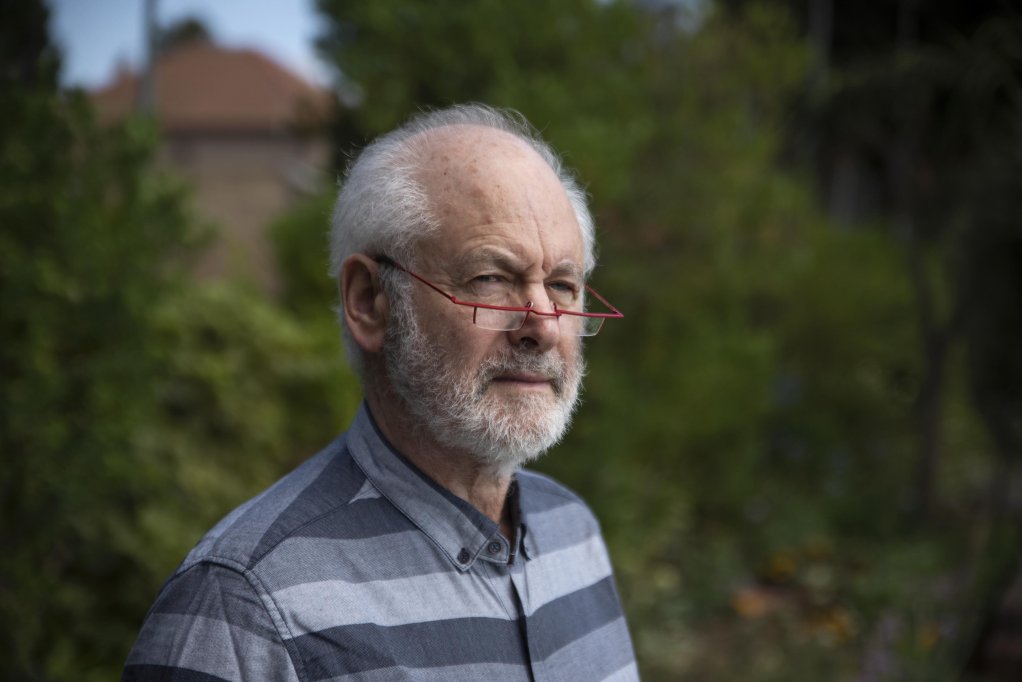

Raymond Suttner is a visiting professor in the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, a senior research associate at the Centre for Change and emeritus professor at UNISA. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His writings cover contemporary politics, history, and social questions, especially issues relating to identities, gender and sexualities. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here